Budget Review 2020 National Treasury Republic of South Africa 26 February 2020

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

Washington, D.C. 20549

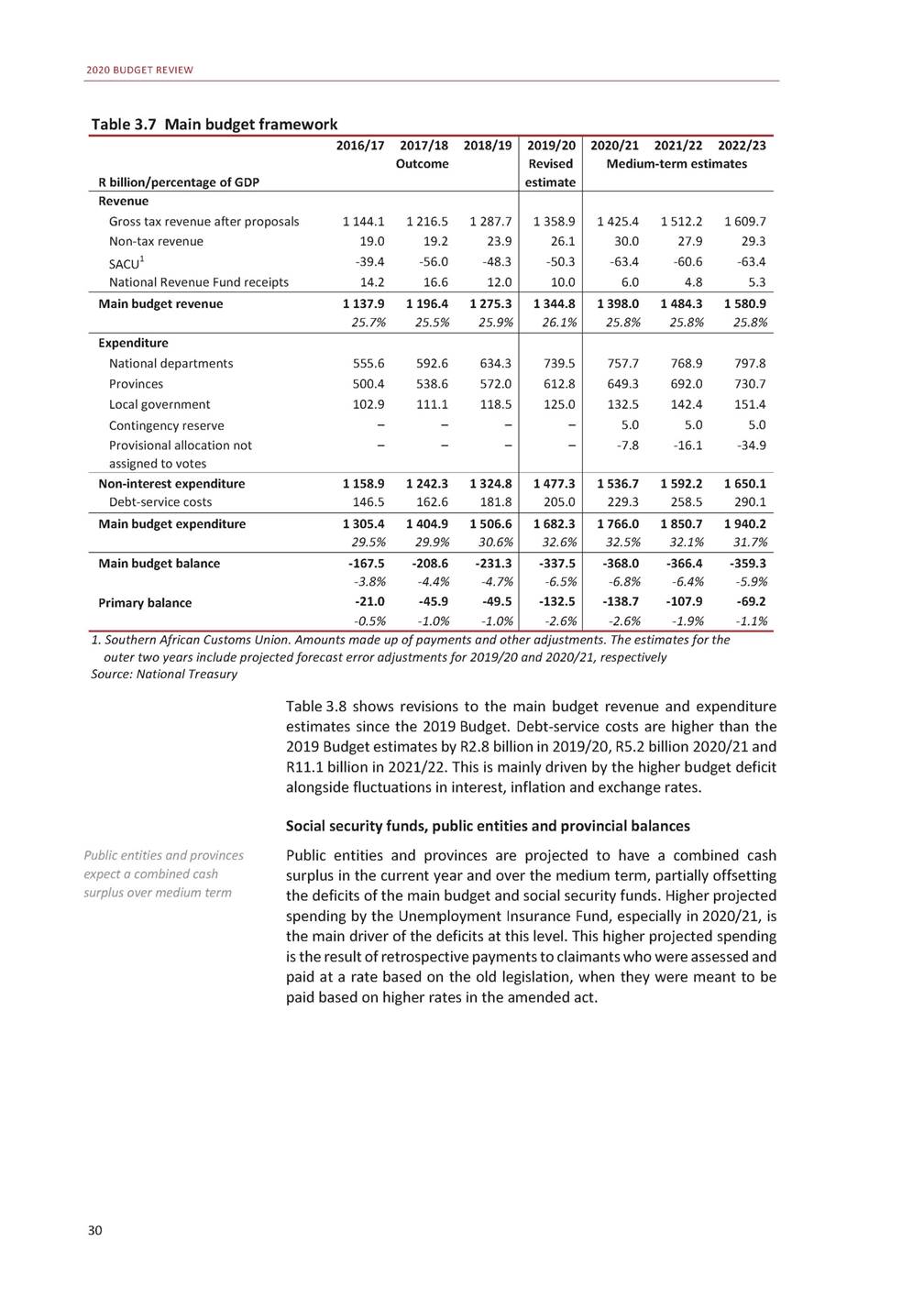

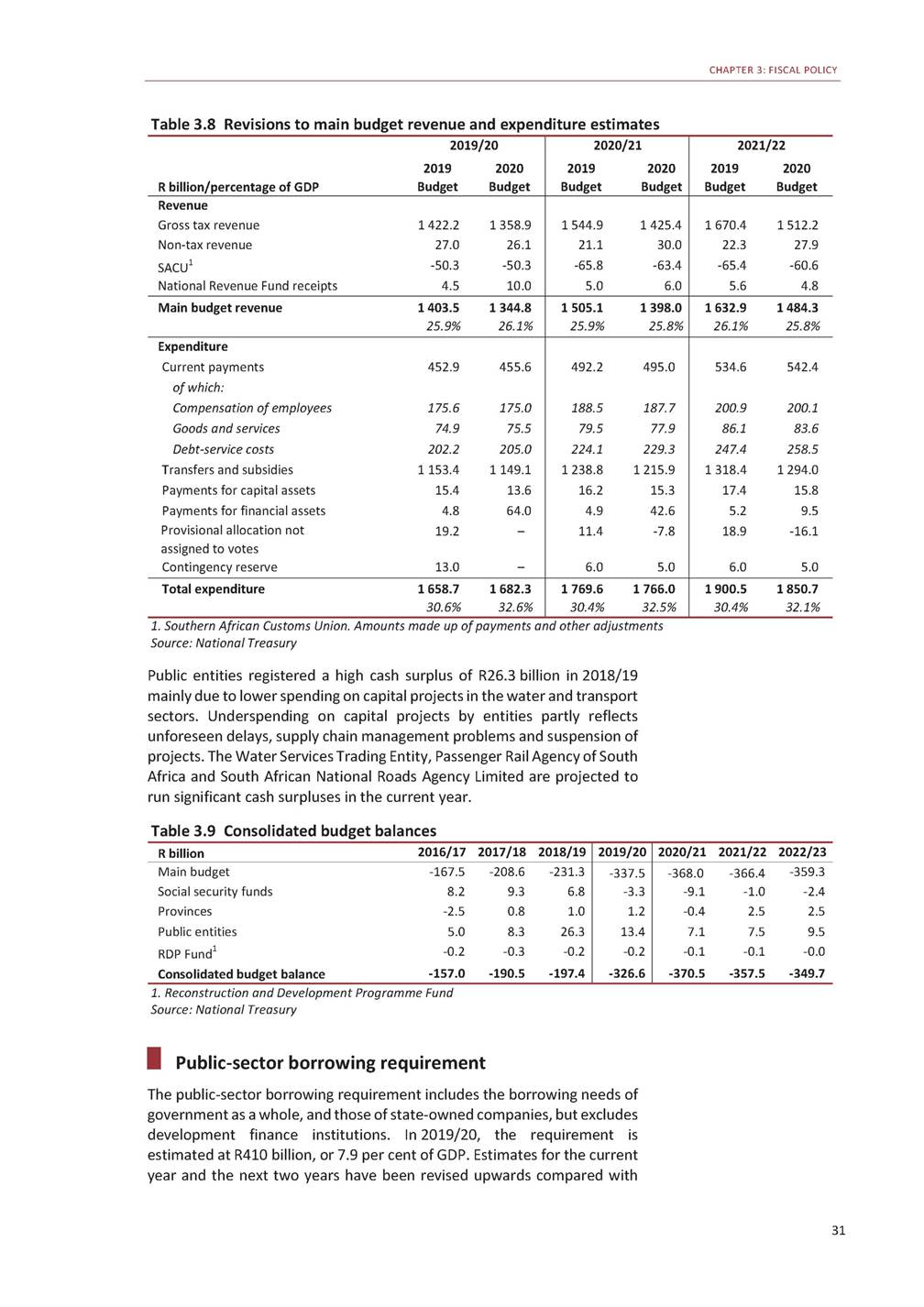

FORM 18-K

For Foreign Governments and Political Subdivisions Thereof

ANNUAL REPORT

OF

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA

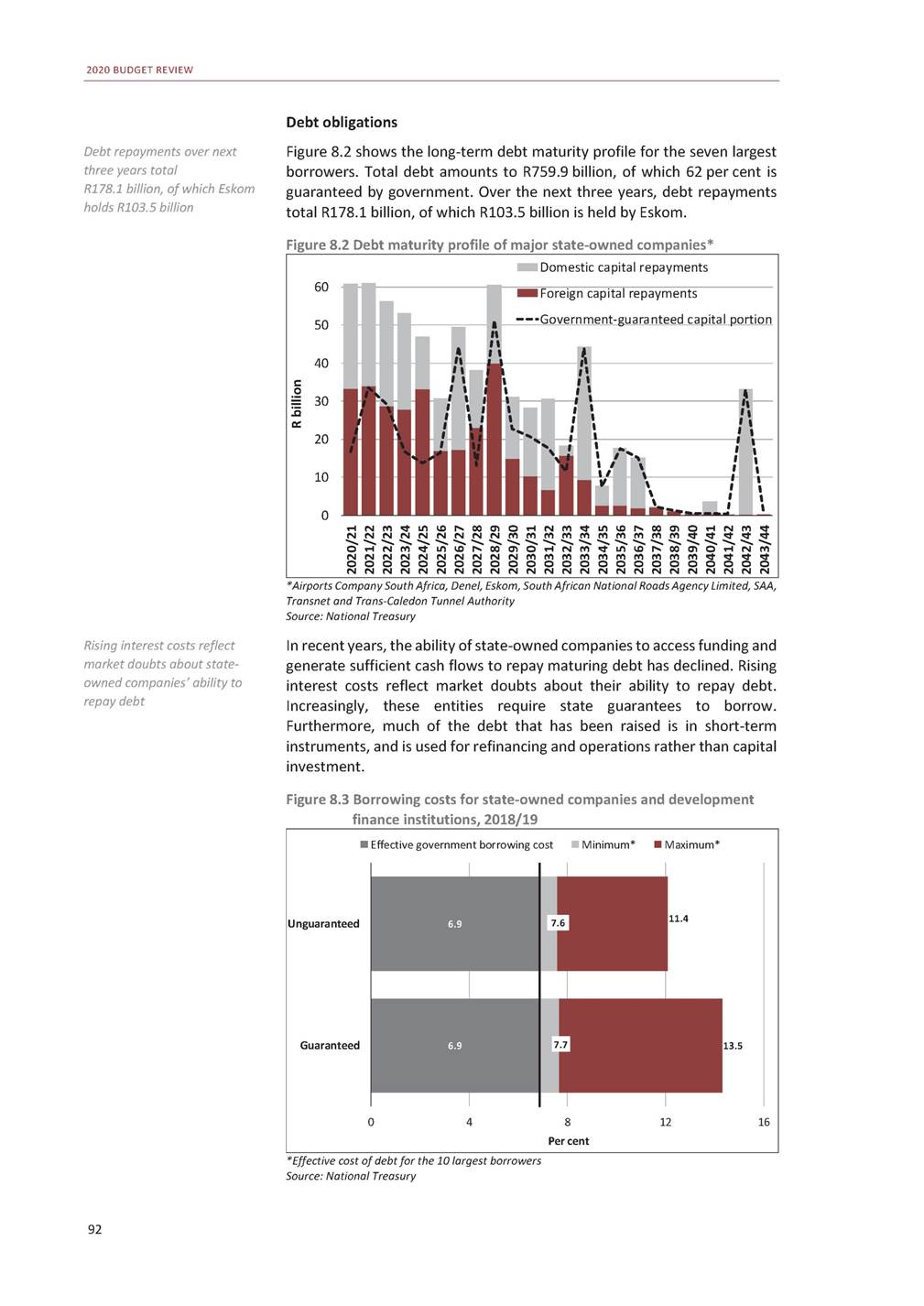

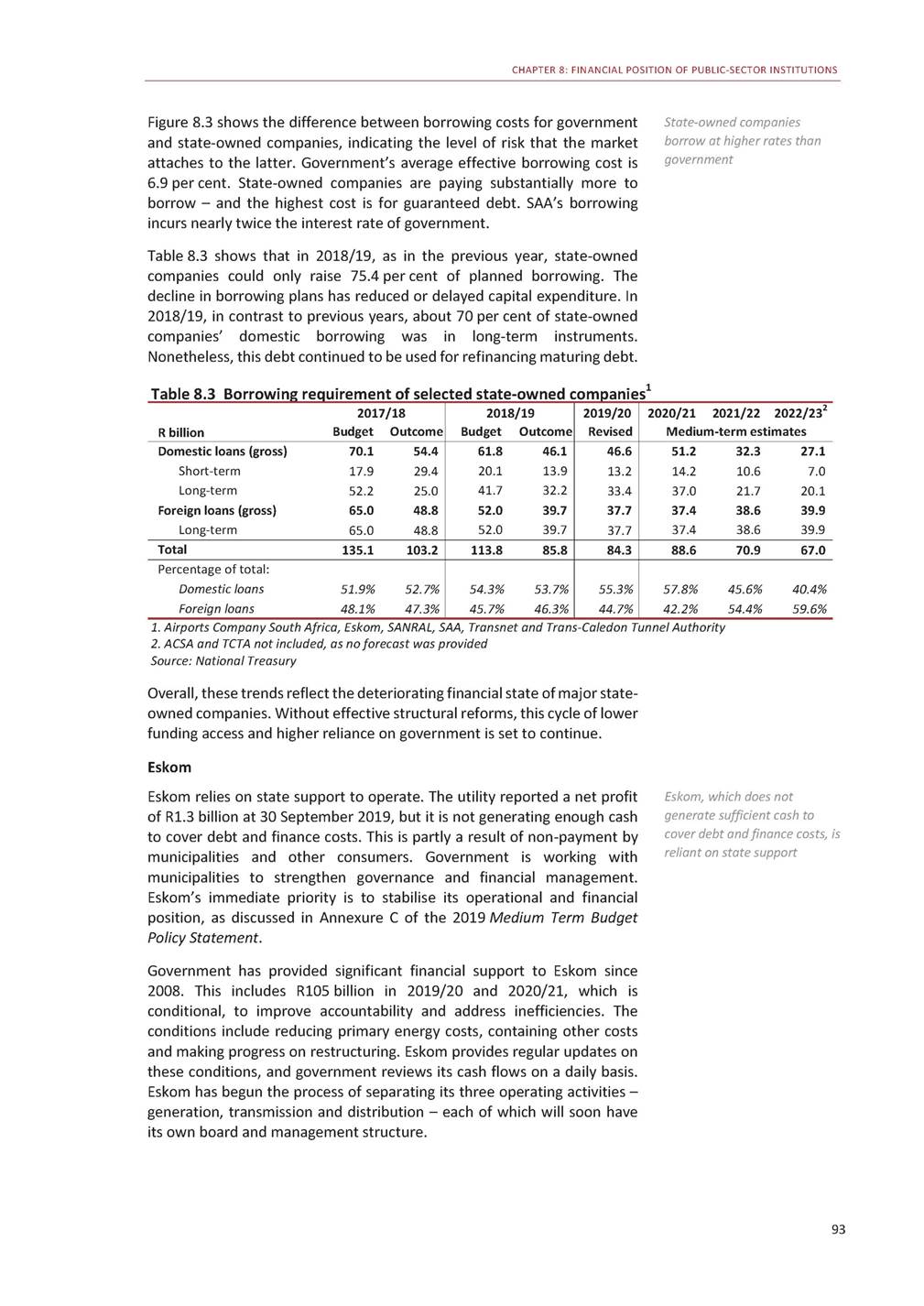

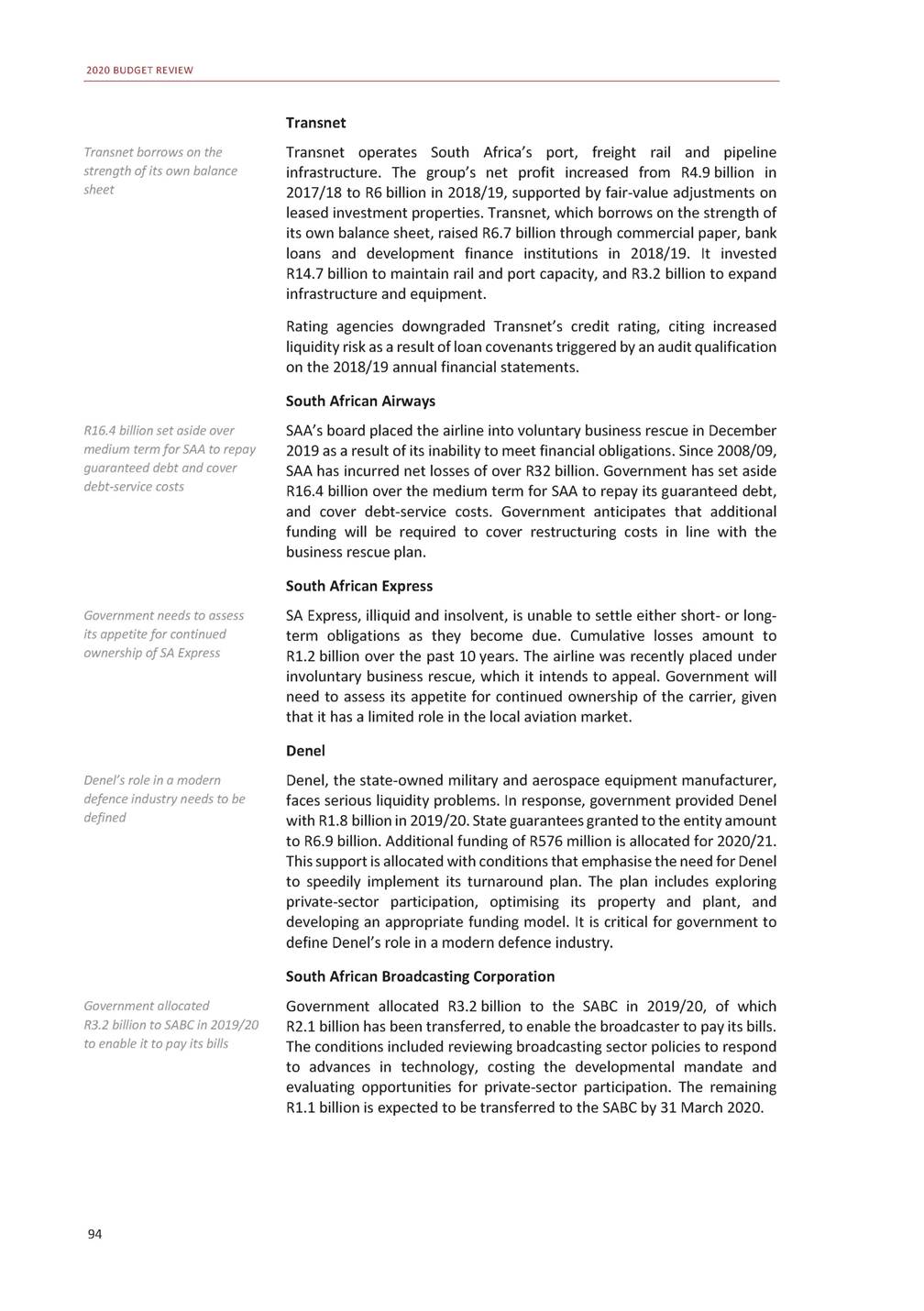

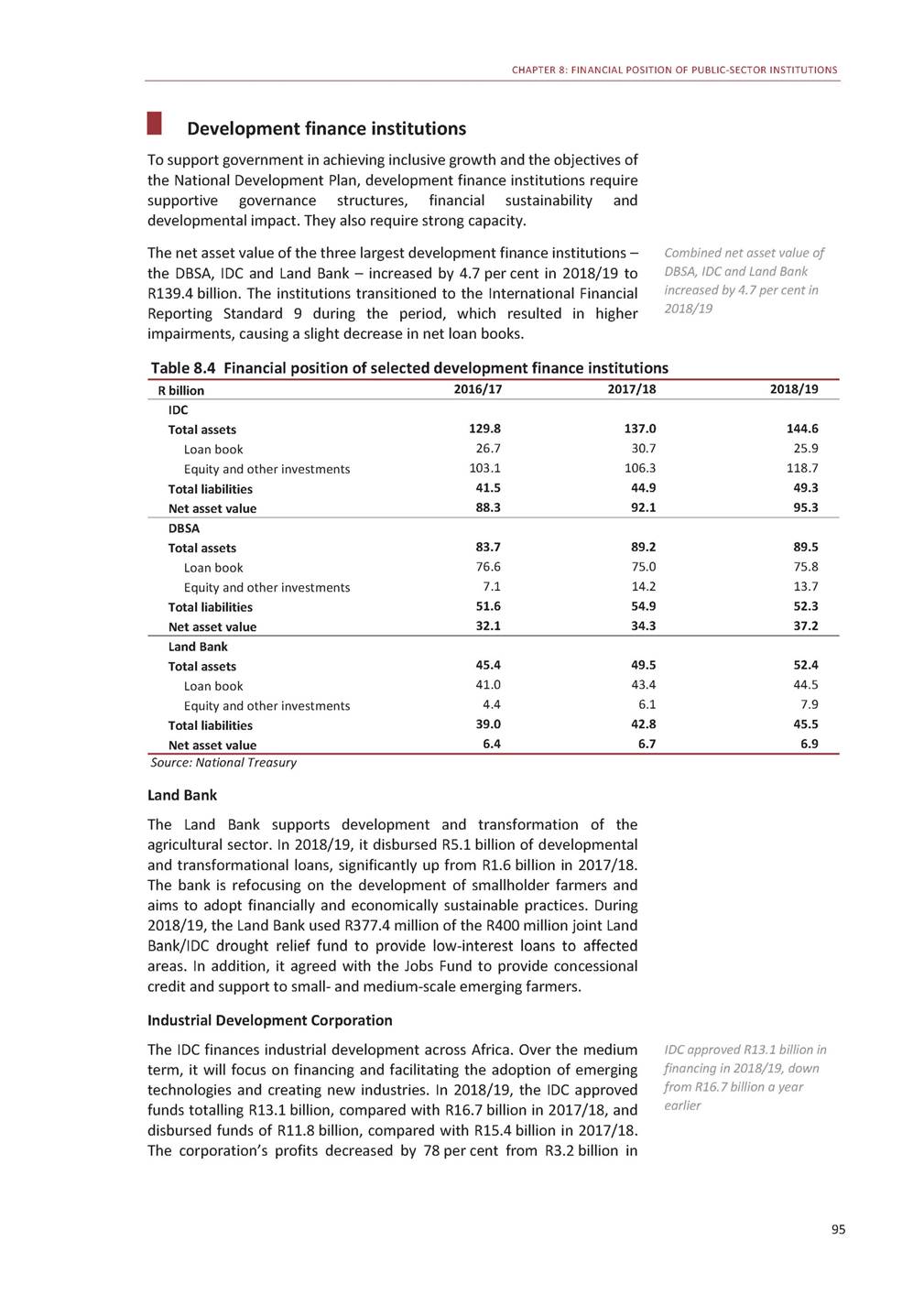

(Name of Registrant)

Date of end of last fiscal year: March 31, 2019

SECURITIES REGISTERED*

(As of the close of the fiscal year)

|

Title of Issue |

|

Amounts as to |

|

Names of |

|

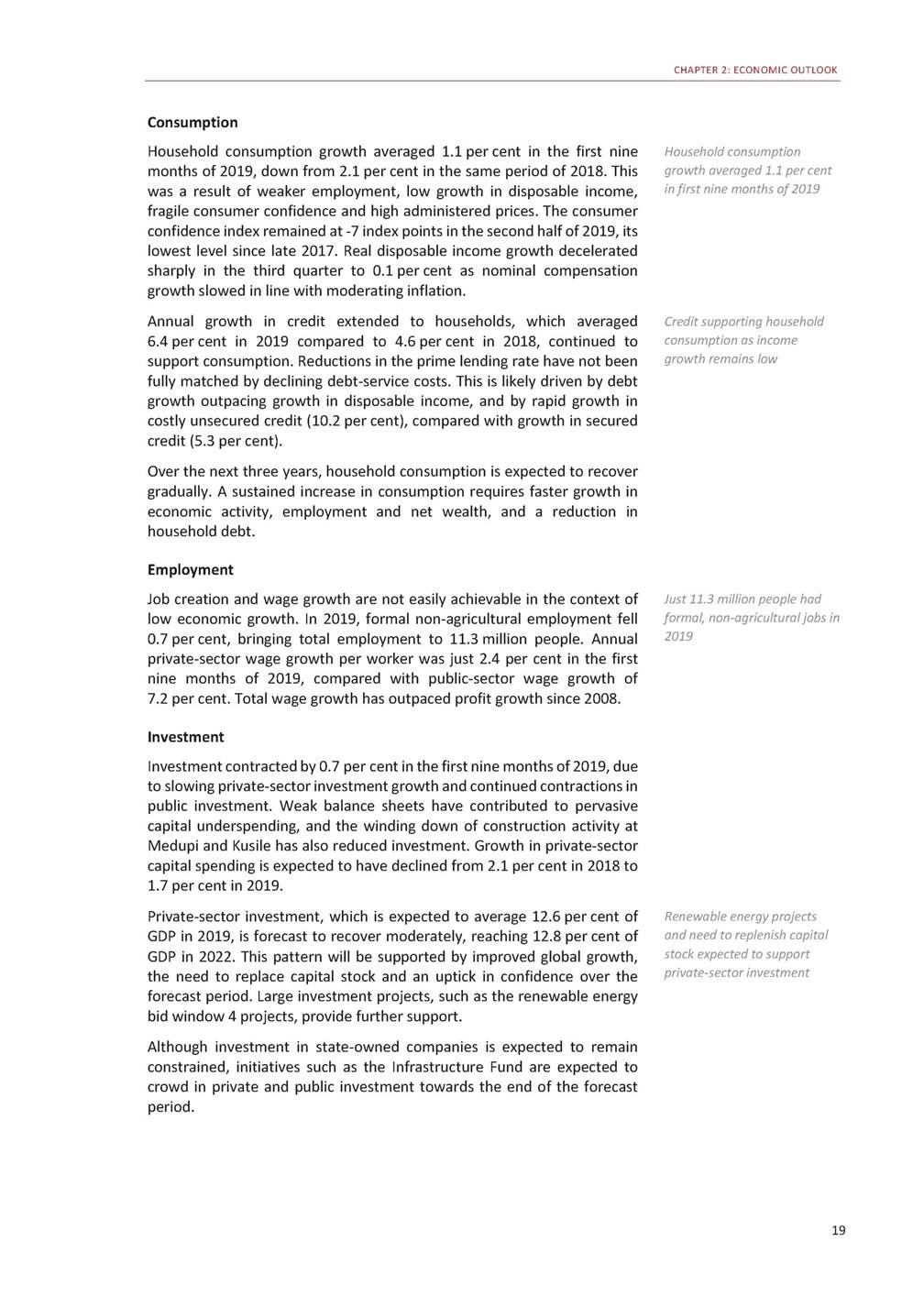

N/A |

|

N/A |

|

N/A |

Name and address of person authorized to receive notices

and communications from the Securities and Exchange Commission:

Ambassador of the Republic of South Africa

Embassy of the Republic of South Africa

3051 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20008

Copies to:

Sachin Davé, Esq.

Allen & Overy LLP

One Bishops Square

London E1 6AD

United Kingdom

* The Registrant is filing this annual report on a voluntary basis.

(1) In respect of each issue of securities of the registrant registered, a brief statement as to:

(a) The general effect of any material modifications, not previously reported, of the rights of the holders of such securities.

There have been no such modifications.

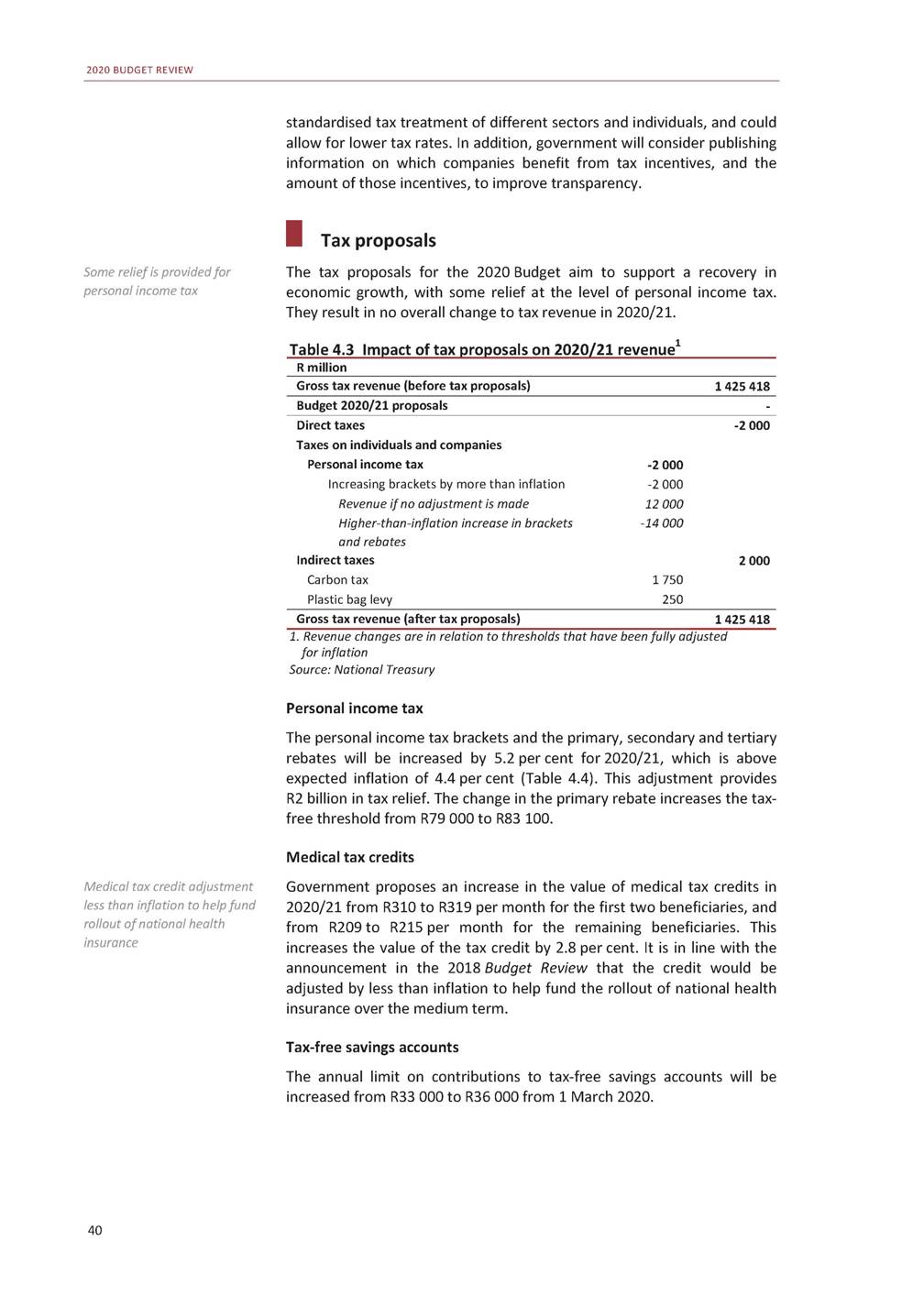

(b) The title and the material provisions of any law, decree or administrative action, not previously reported, by reason of which the security is not being serviced in accordance with the terms thereof.

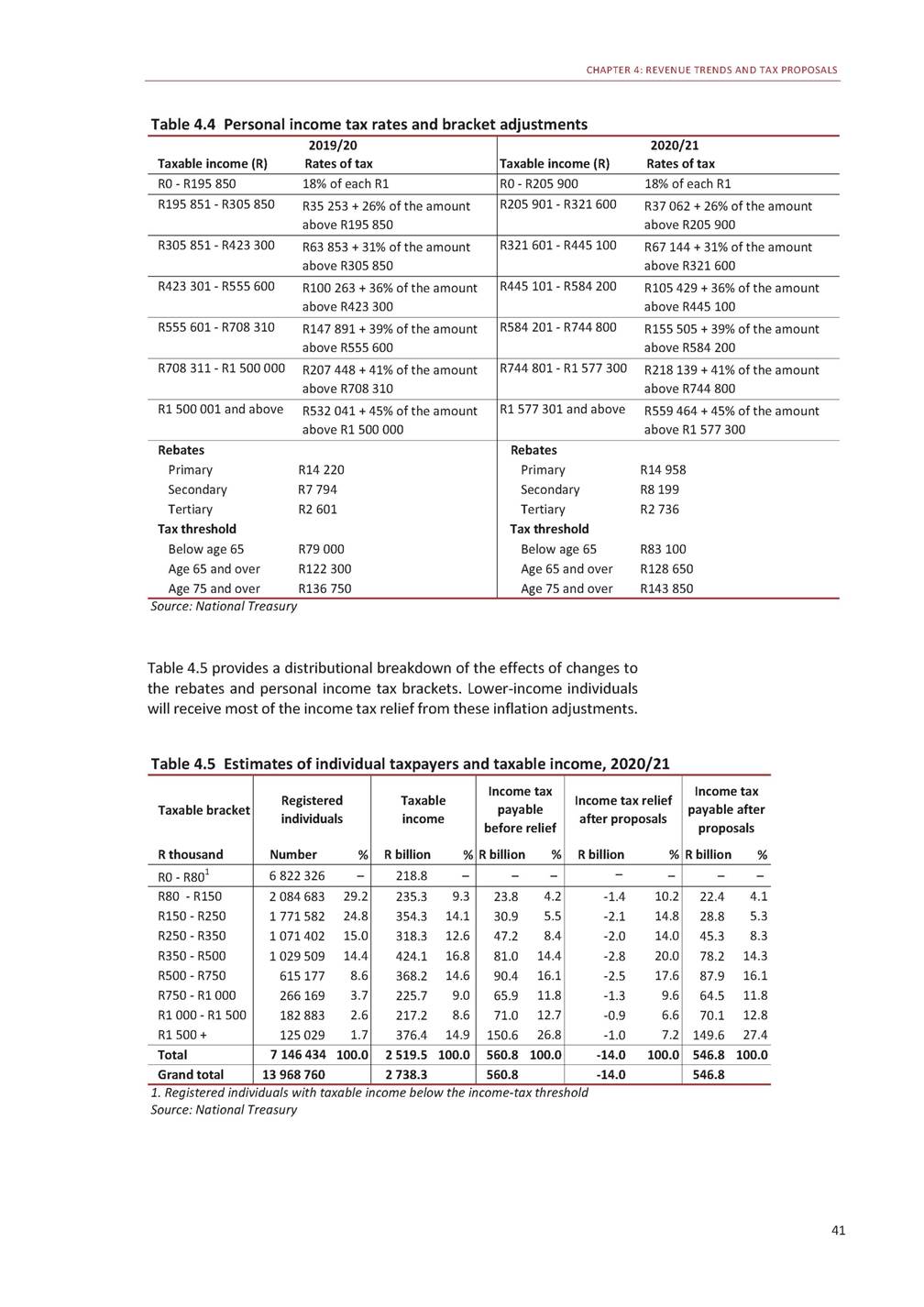

There has been no such law, decree or administrative action.

(c) The circumstances of any other failure, not previously reported, to pay principal, interest or any sinking fund or amortization installment.

There has been no such failure.

(2) A statement as of the close of the last fiscal year of the registrant, giving the total outstanding of:

(a) Internal funded debt of the registrant. (Total to be stated in the currency of the registrant. If any internal funded debt is payable in a foreign currency, it should not be included under this paragraph (a), but under paragraph (b) of this item.)

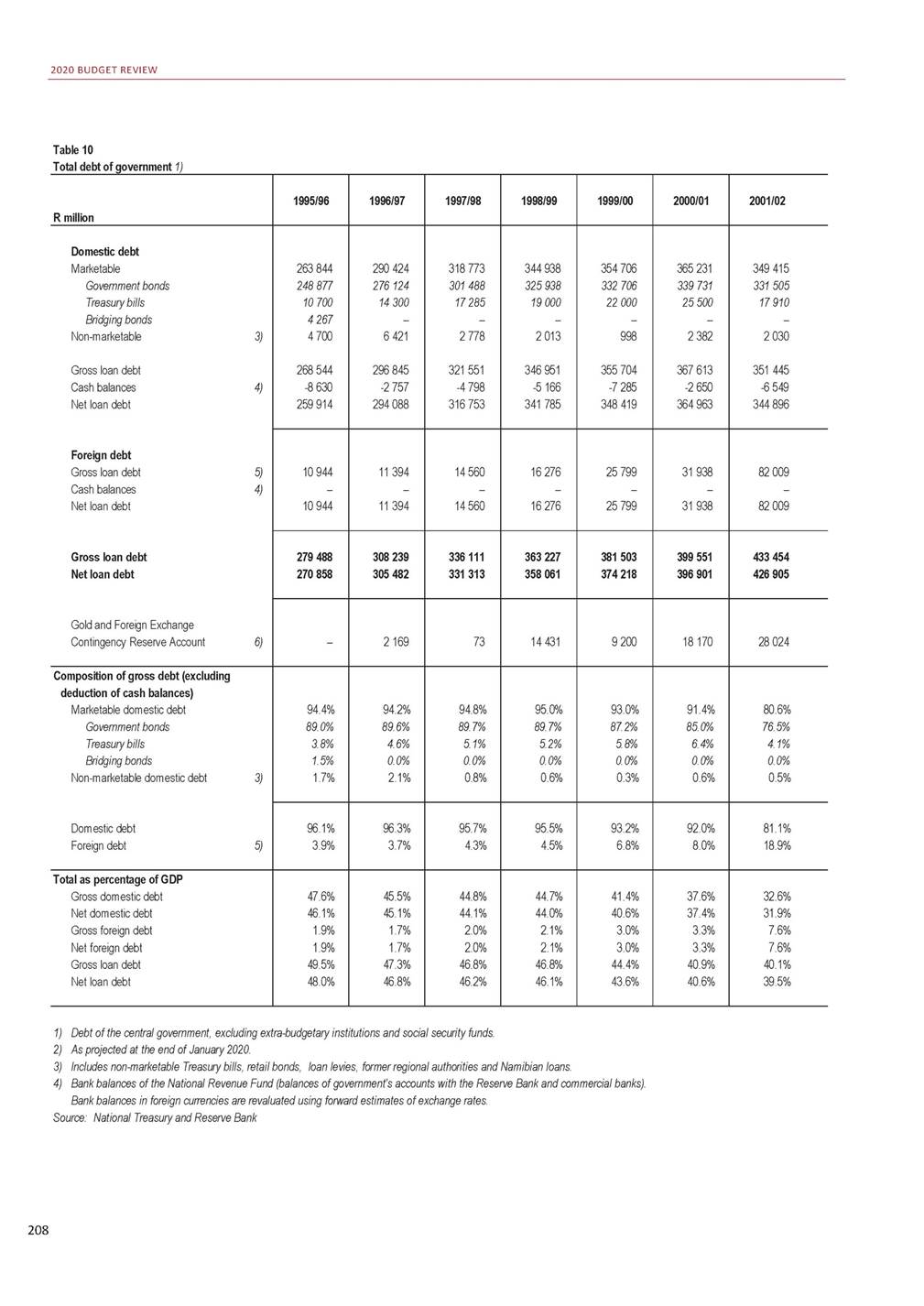

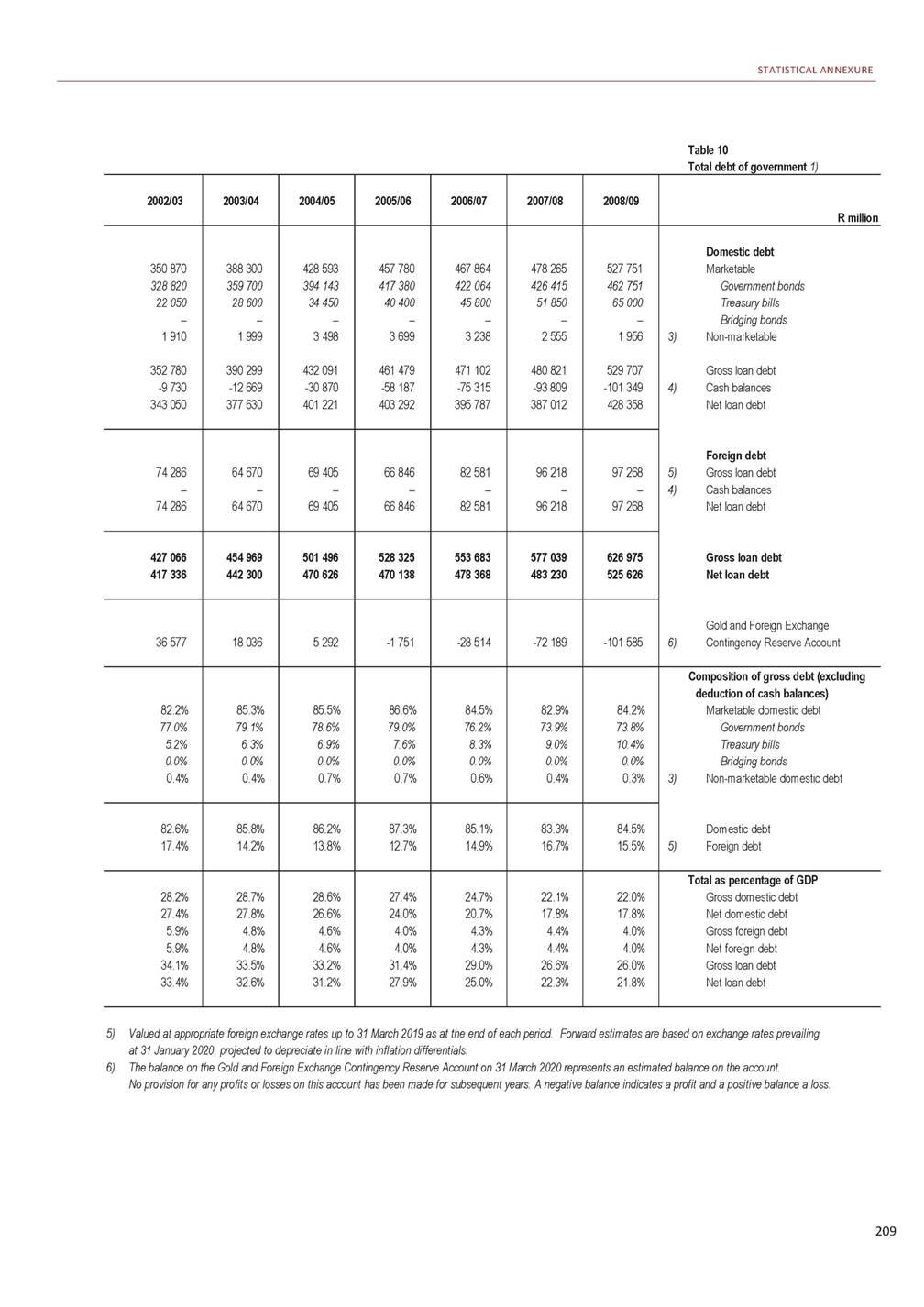

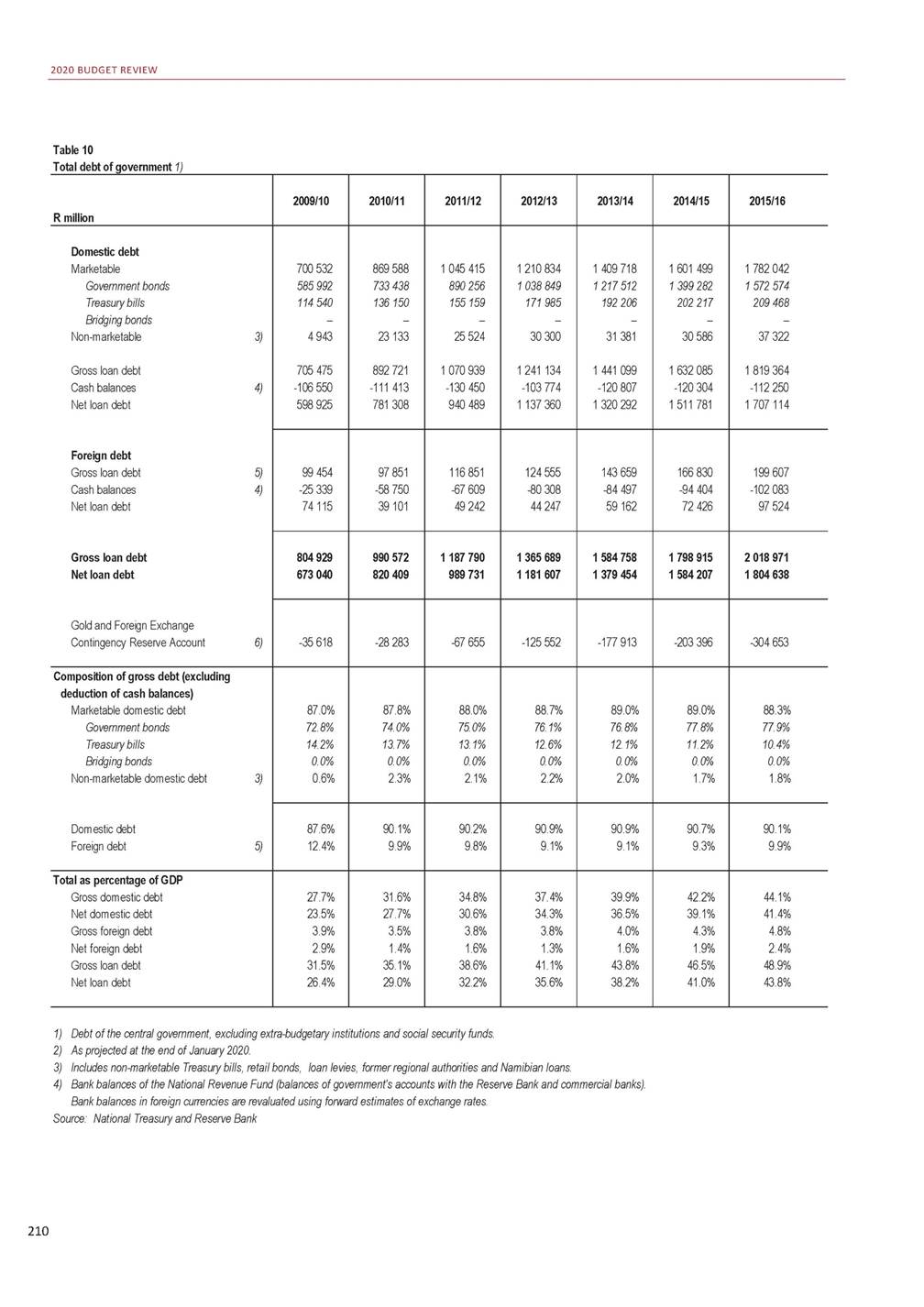

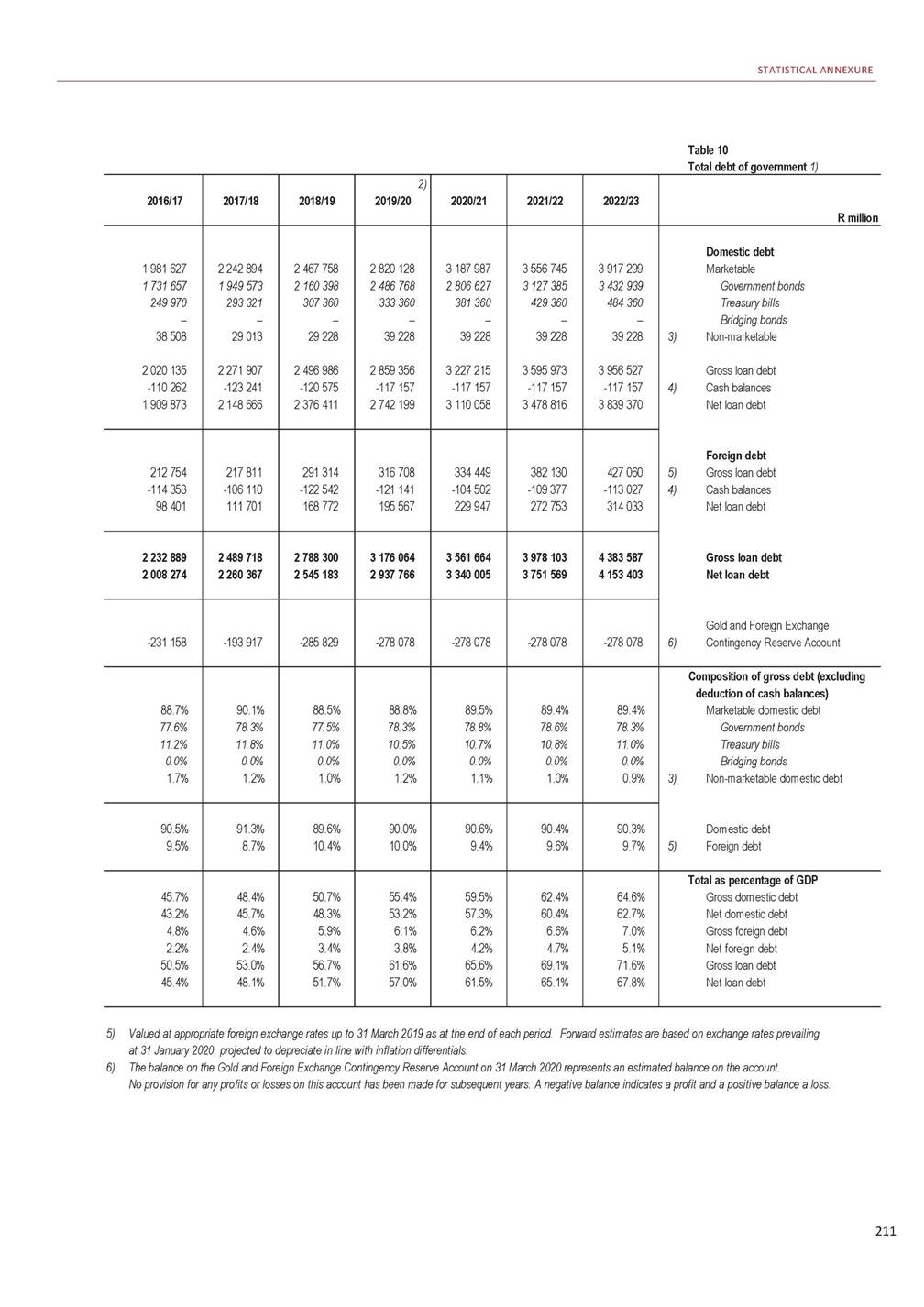

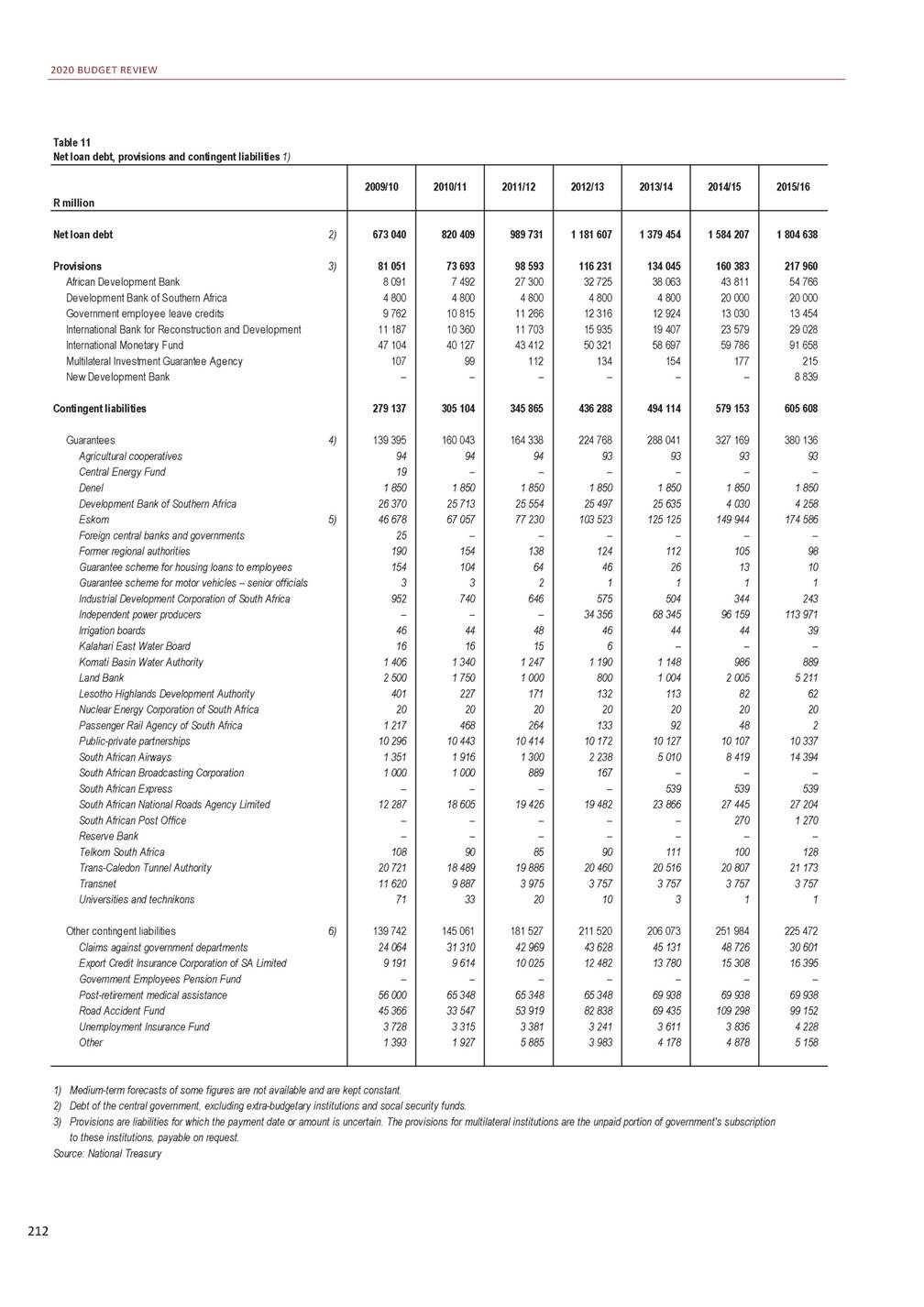

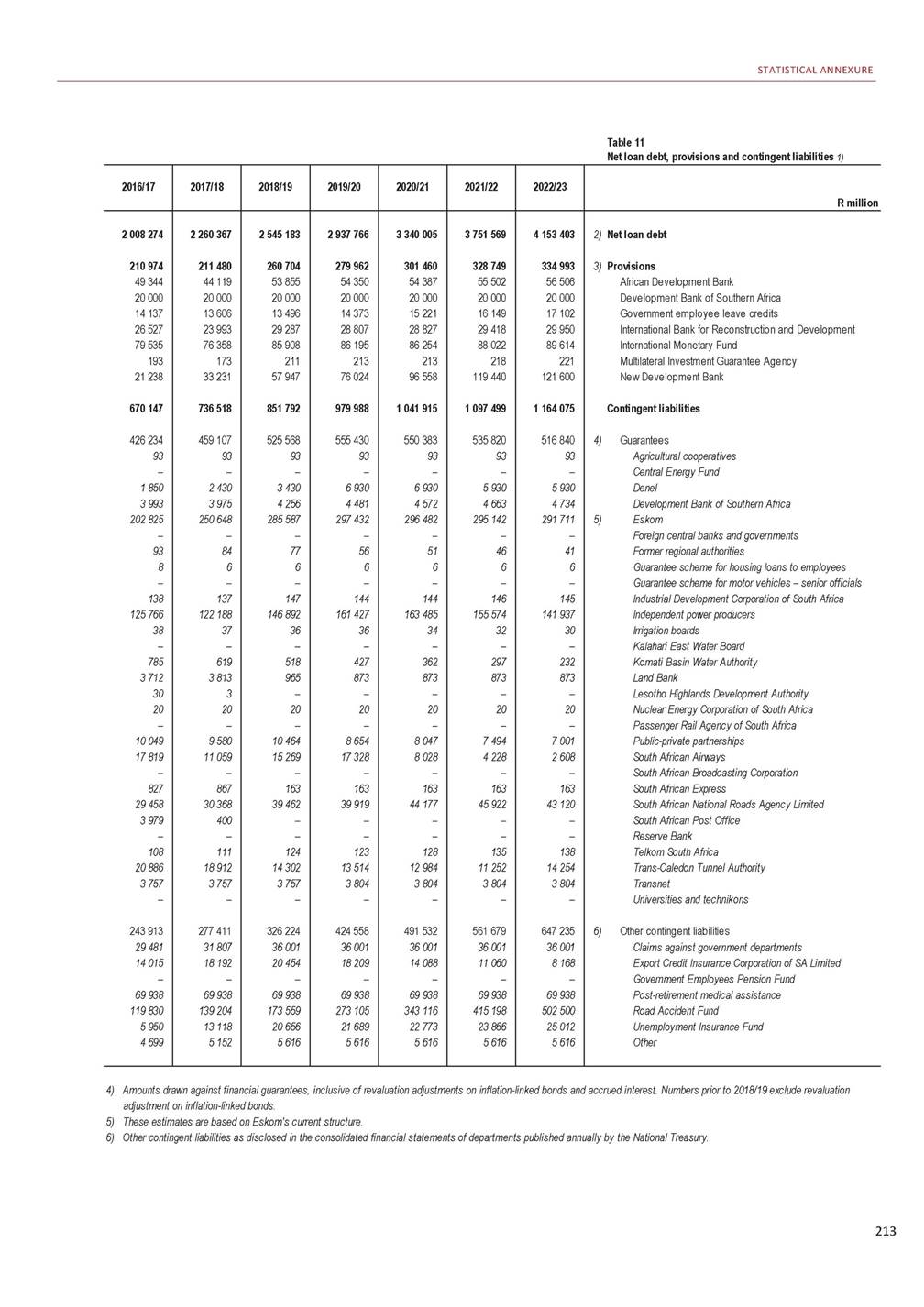

See “Tables and Supplementary Information,” pages 82-91 of Exhibit 99.E.

(b) External funded debt of the registrant. (Totals to be stated in the respective currencies in which payable. No statement need be furnished as to intergovernmental debt.)

See “Tables and Supplementary Information,” pages 91-93 of Exhibit 99.E.

(3) A statement giving the title, date of issue, date of maturity, interest rate and amount outstanding, together with the currency or currencies in which payable, of each issue of funded debt of the registrant outstanding as of the close of the last fiscal year of the registrant.

See “Tables and Supplementary Information,” pages 88 and 91-93 of Exhibit 99.E.

(4) (a) As to each issue of securities of the registrant which is registered, there should be furnished a breakdown of the total amount outstanding, as shown in Item (3), into the following:

(1) Total amount held by or for the account of the registrant.

Not applicable.

(2) Total estimated amount held by nationals of the registrant.

Not applicable.

(3) Total amount otherwise outstanding.

Not applicable.

(b) If a substantial amount is set forth in answer to paragraph (a)(1) above, describe briefly the method employed by the registrant to reacquire such securities.

Not applicable.

(5) A statement as of the close of the last fiscal year of the registrant giving the estimated total of:

(a) Internal floating indebtedness of the registrant. (Total to be stated in the currency of the registrant.)

See “Tables and Supplementary Information,” pages 88-91 of Exhibit 99.E.

(b) External floating indebtedness of the registrant. (Total to be stated in the respective currencies in which payable.)

The registrant has no external floating indebtedness.

(6) Statements of the receipts, classified by source, and of the expenditures, classified by purpose, of the registrant for each fiscal year of the registrant ended since the close of the latest fiscal year for which such information was previously reported. These statements should be so itemized as to be reasonably informative and should cover both ordinary and extraordinary receipts and expenditures; there should be

indicated separately, if practicable, the amount of receipts pledged or otherwise specifically allocated to any issue registered, indicating the issue.

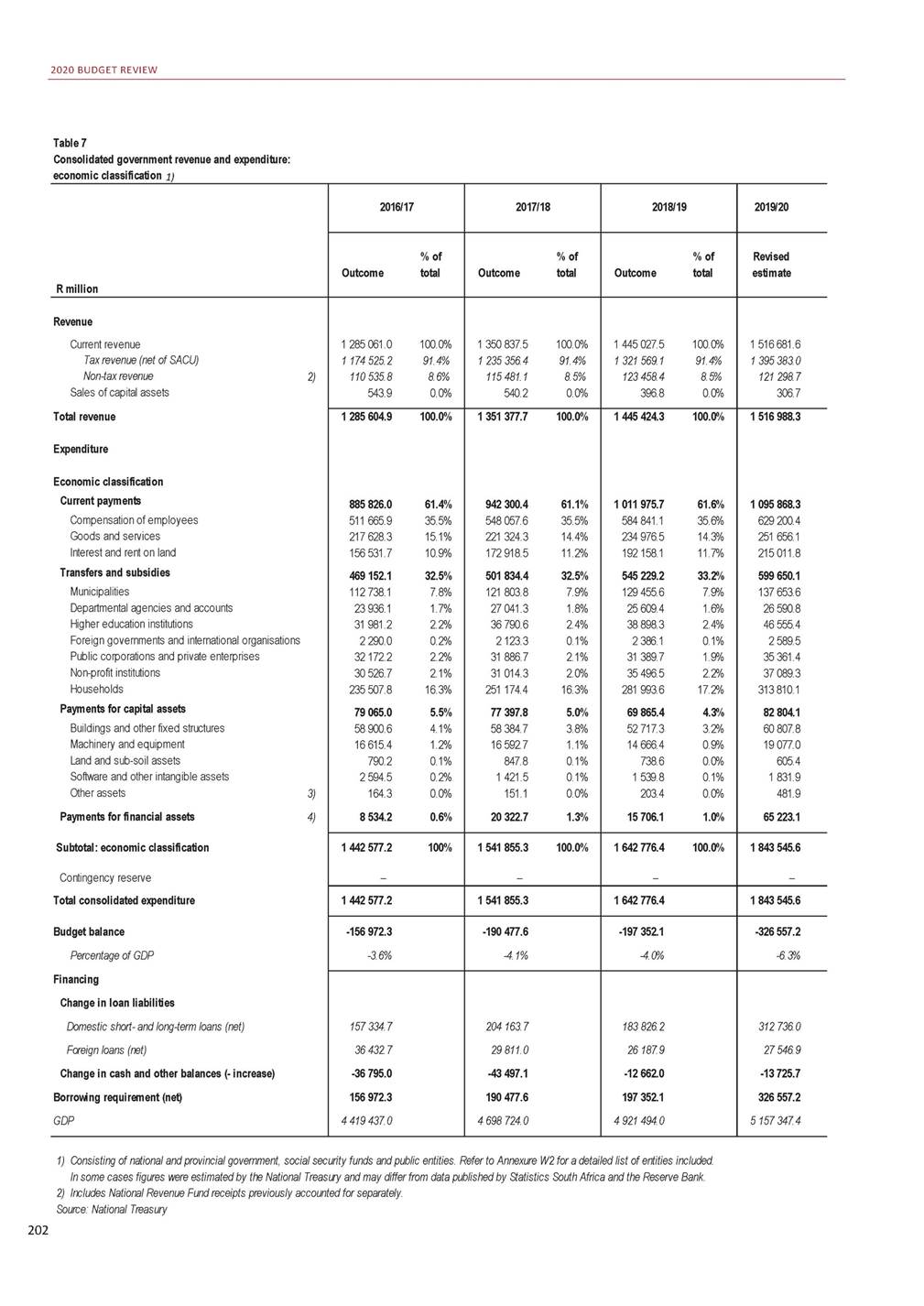

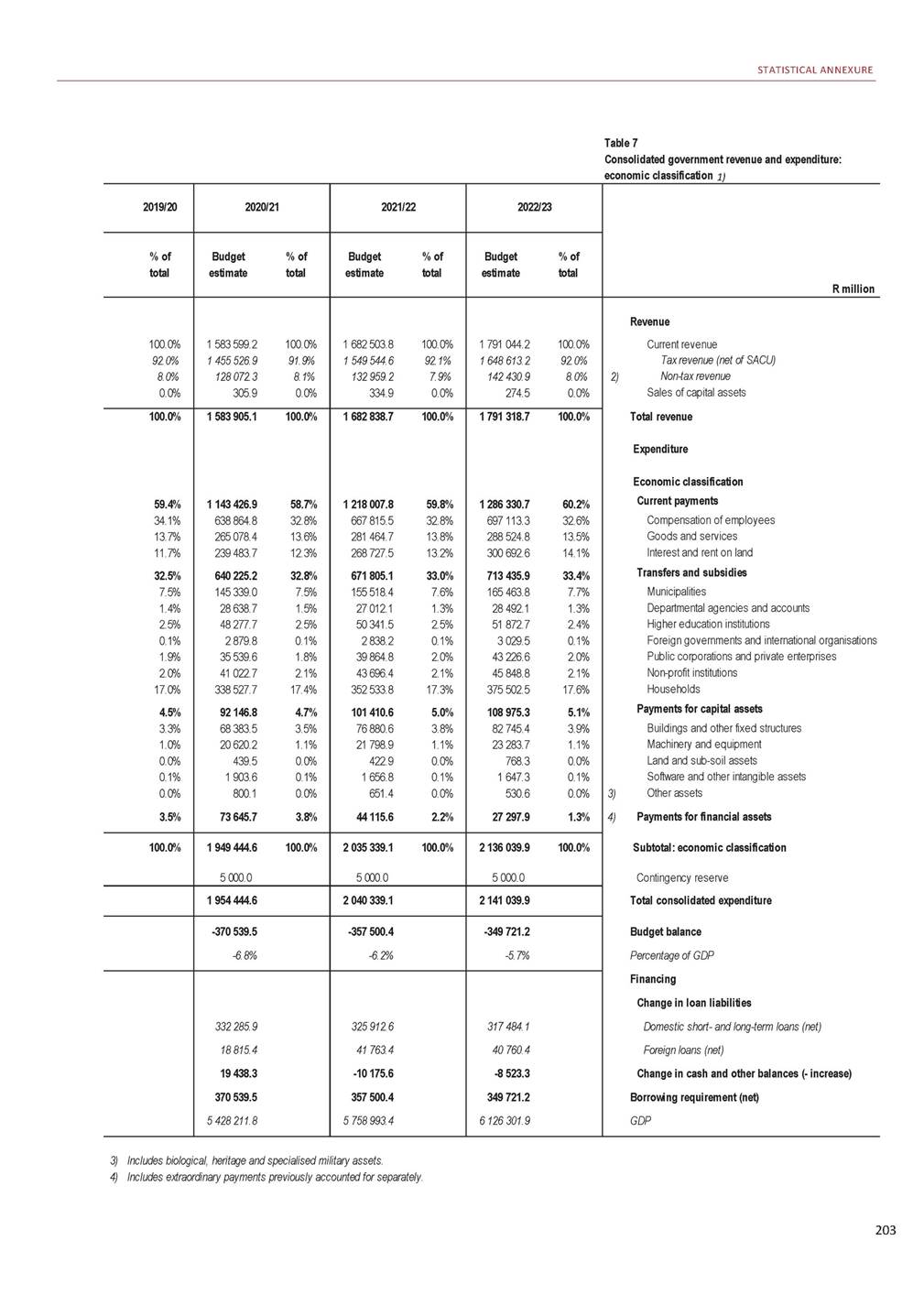

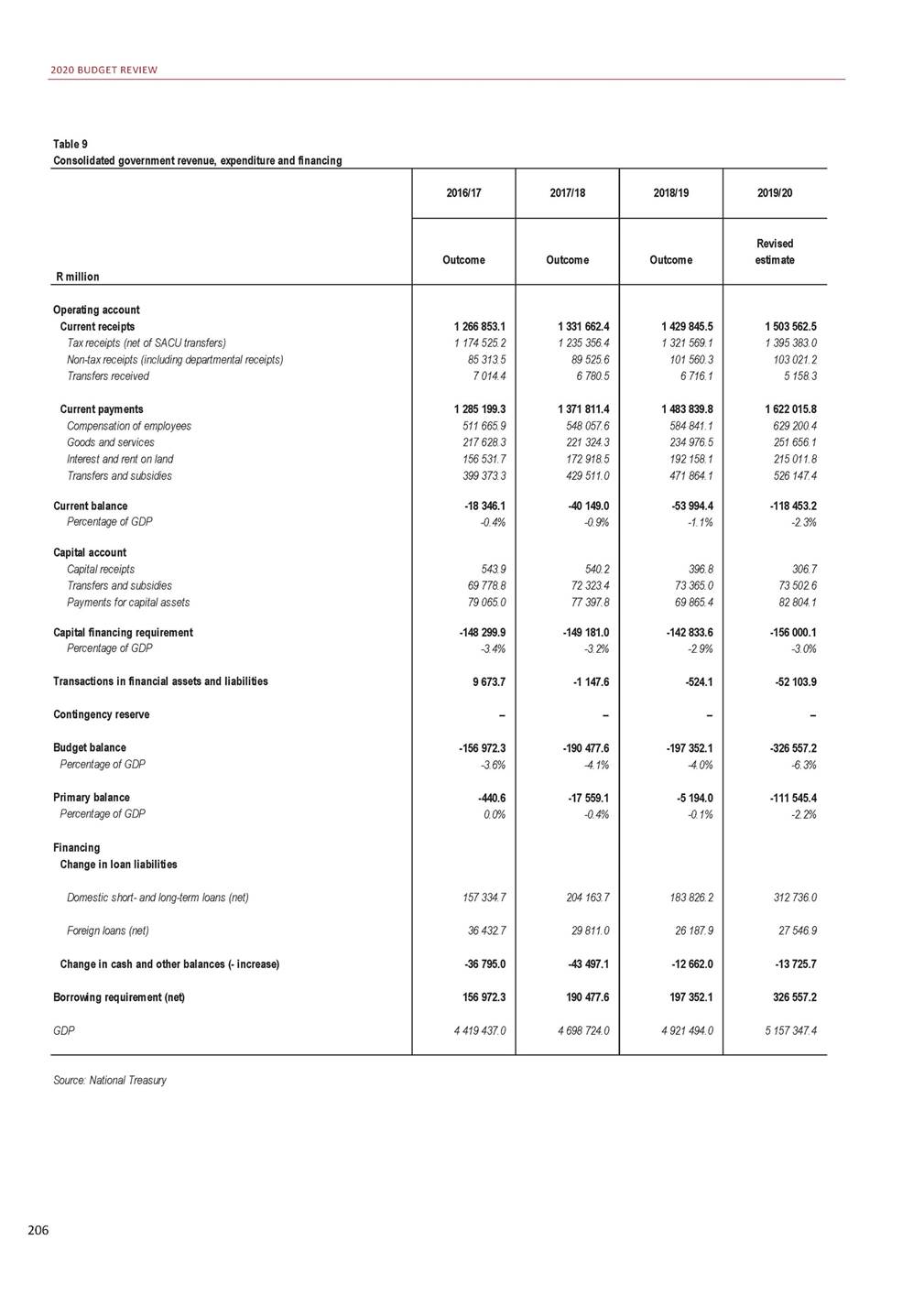

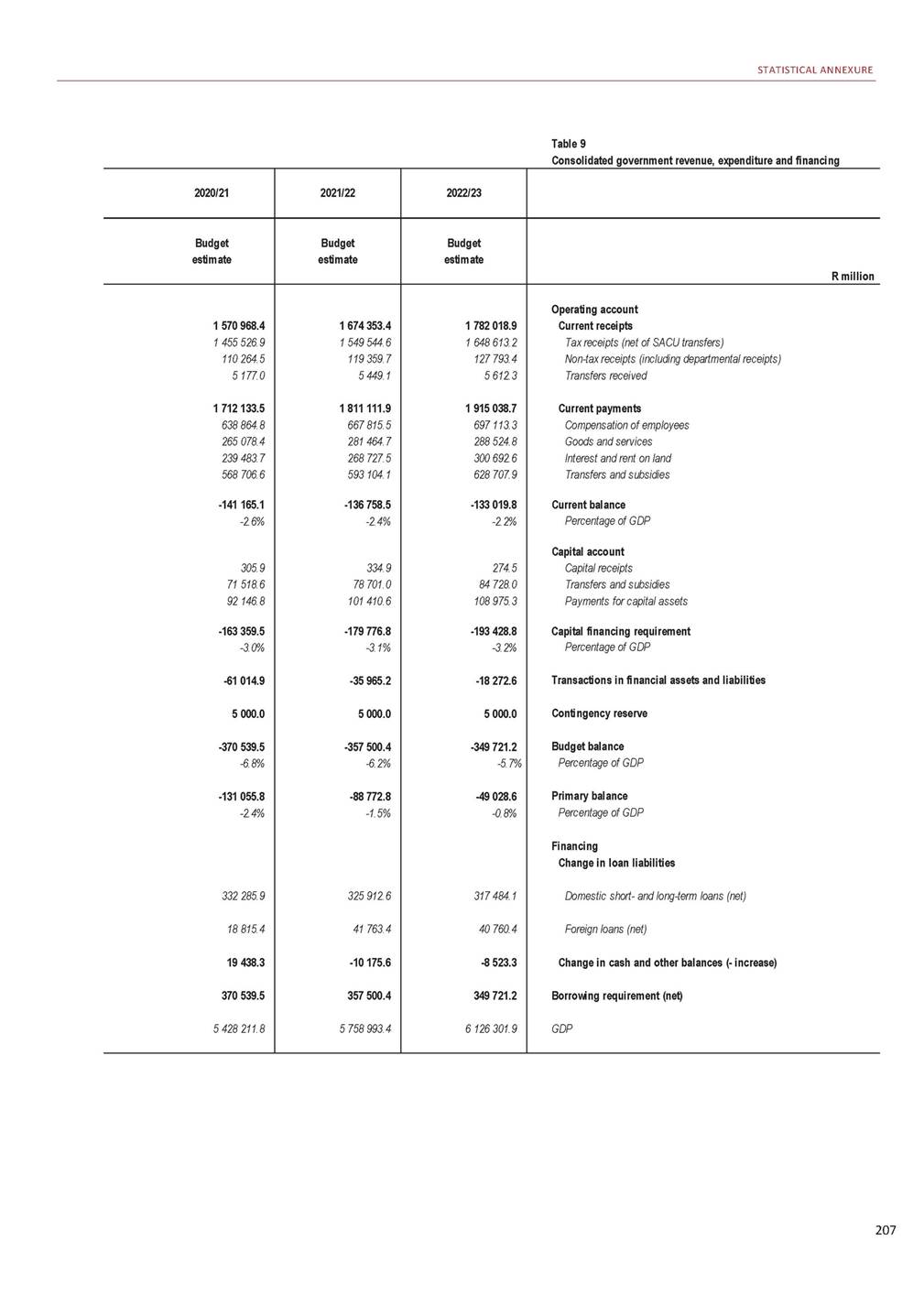

See “Public Finance—2019-2020 National Budget and Consolidated Government Budgets” and “Public Finance—Consolidated Government Revenue,” pages 76-78 and pages 81-82, respectively, of Exhibit 99.E.

(7) (a) If any foreign exchange control, not previously reported, has been established by the registrant, briefly describe the effect of any such action, not previously reported.

See “Monetary and Financial System—Exchange Controls,” pages 52-54 of Exhibit 99.E. No foreign exchange control not previously reported was established by the registrant during fiscal year 2019.

(a) If any foreign exchange control previously reported has been discontinued or materially modified, briefly describe the effect of any such action, not previously reported.

See “Monetary and Financial System—Exchange Controls,” pages 52-54 of Exhibit 99.E.

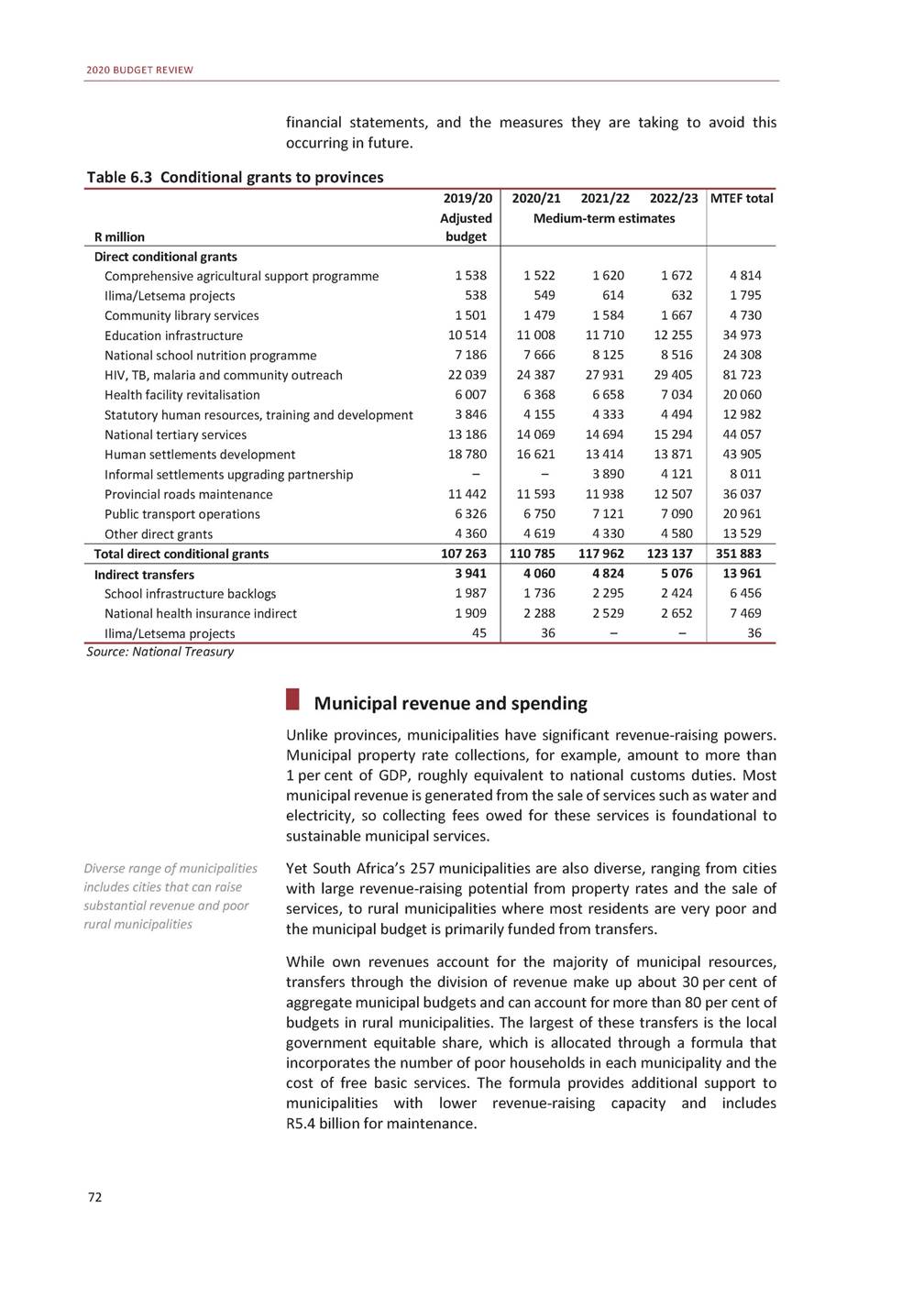

(8) Brief statements as of a date reasonably close to the date of the filing of this report (indicating such date), in respect of the note issue and gold reserves of the central bank of issue of the registrant, and of any further gold stocks held by the registrant.

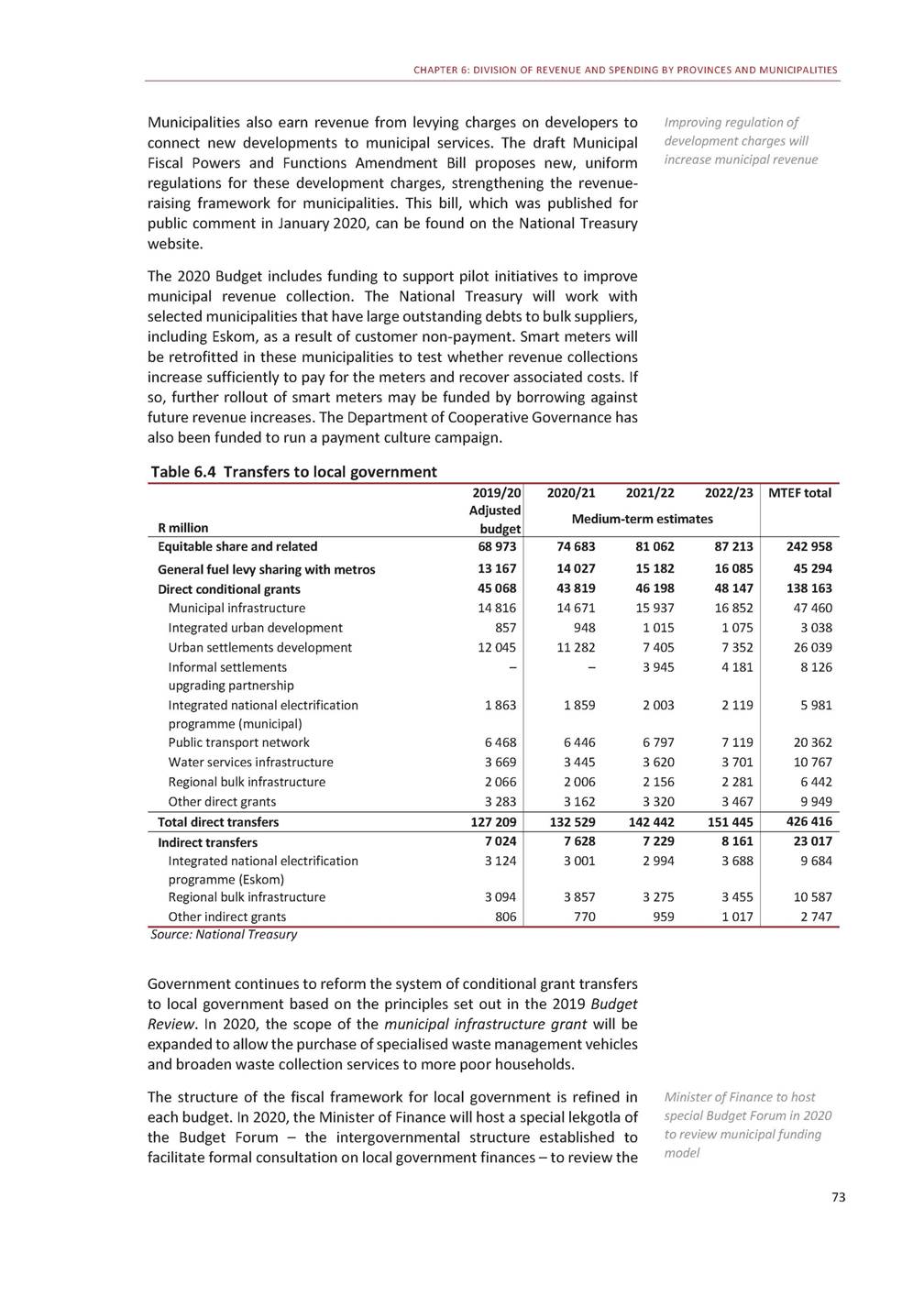

See “Monetary and Financial System—Gold and Foreign Exchange Contingency Reserve Account (GFECRA),” page 54 of Exhibit 99.E.

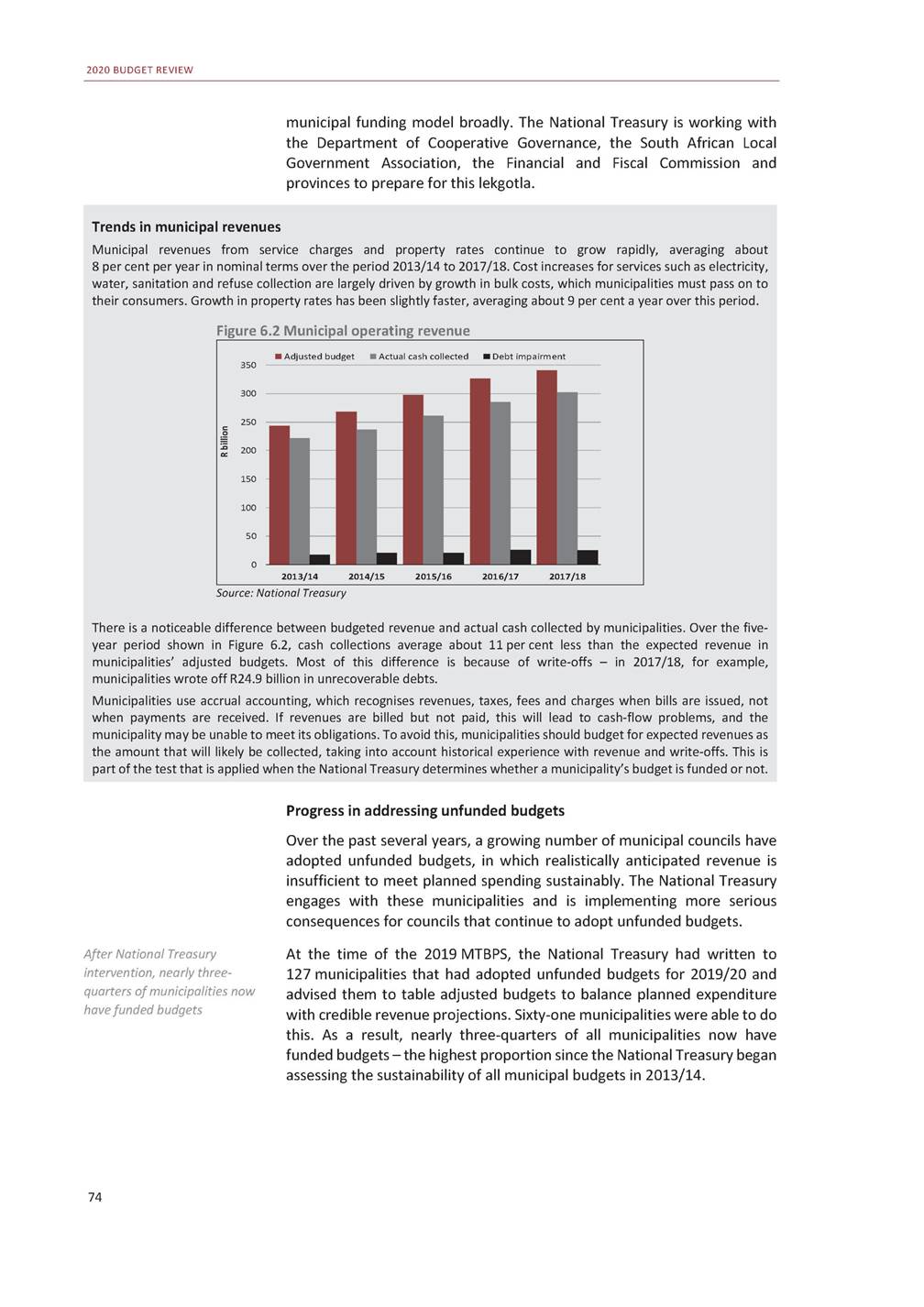

(9) Statements of imports and exports of merchandise for each year ended since the close of the latest year for which such information was previously reported. Such statements should be reasonably itemized so far as practicable as to commodities and as to countries. They should be set forth in terms of value and of weight or quantity; if statistics have been established only in terms of value, such will suffice.

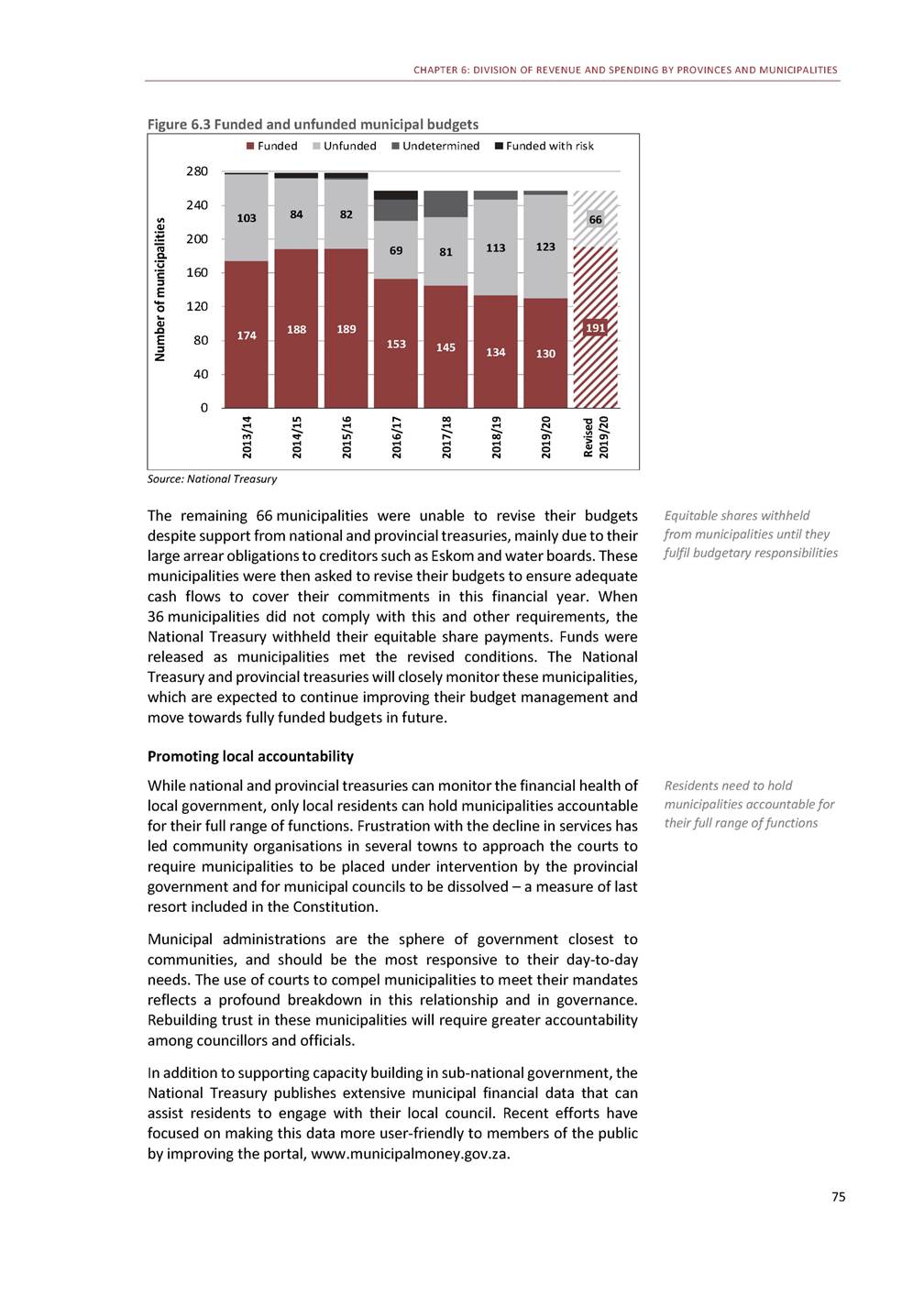

See “The External Sector of the Economy—Foreign Trade,” pages 54-56 of Exhibit 99.E.

(10) The balances of international payments of the registrant for each fiscal year ended since the close of the latest fiscal year for which such information was previously reported. The statements for such balances should conform, if possible, to the nomenclature and form used in the “Statistical Handbook of the League of Nations.” (These statements need be furnished only if the registrant has published balances of international payments.)

See “The External Sector of the Economy—Balance of Payments,” pages 56-60 of Exhibit 99.E.

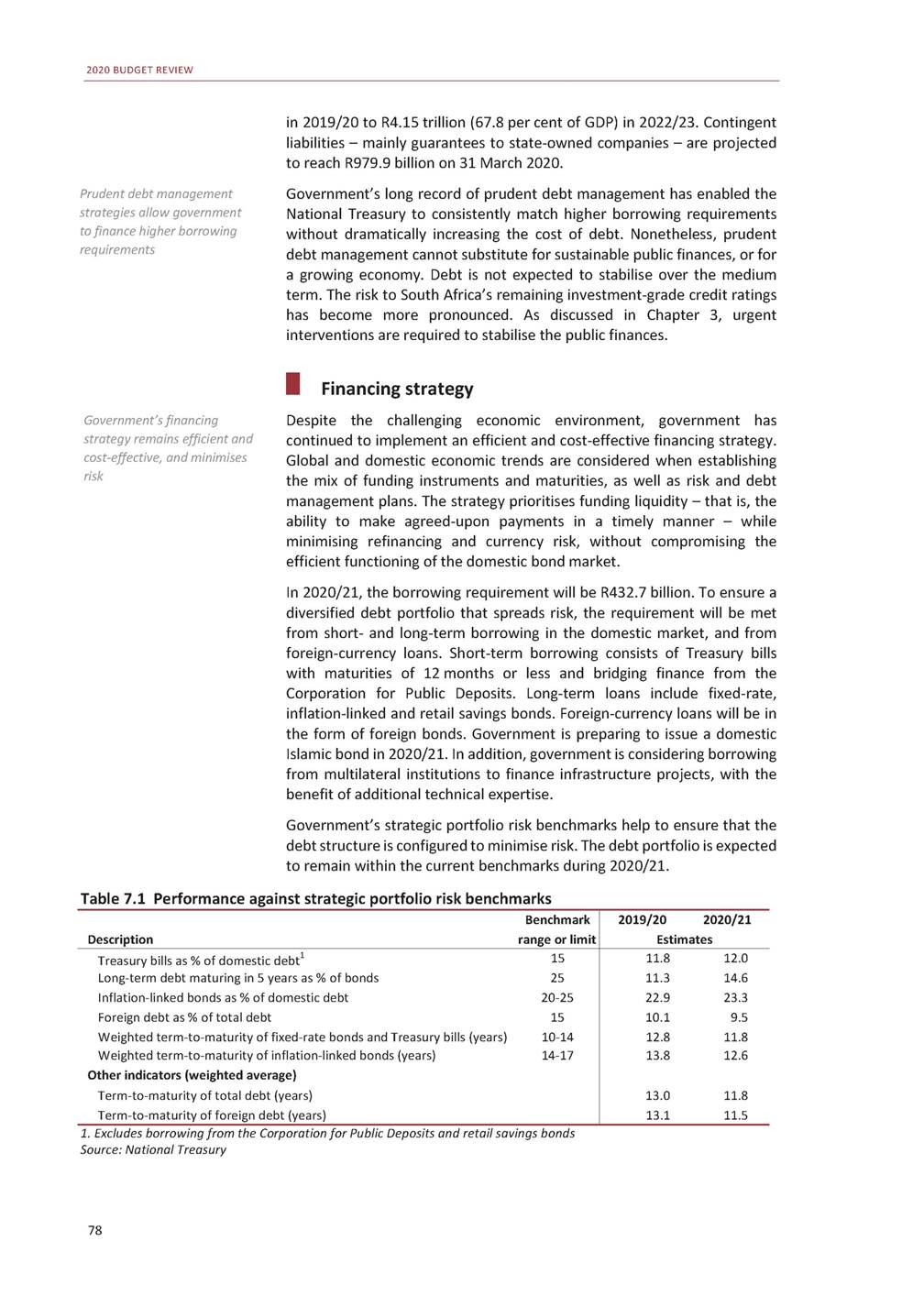

This annual report comprises:

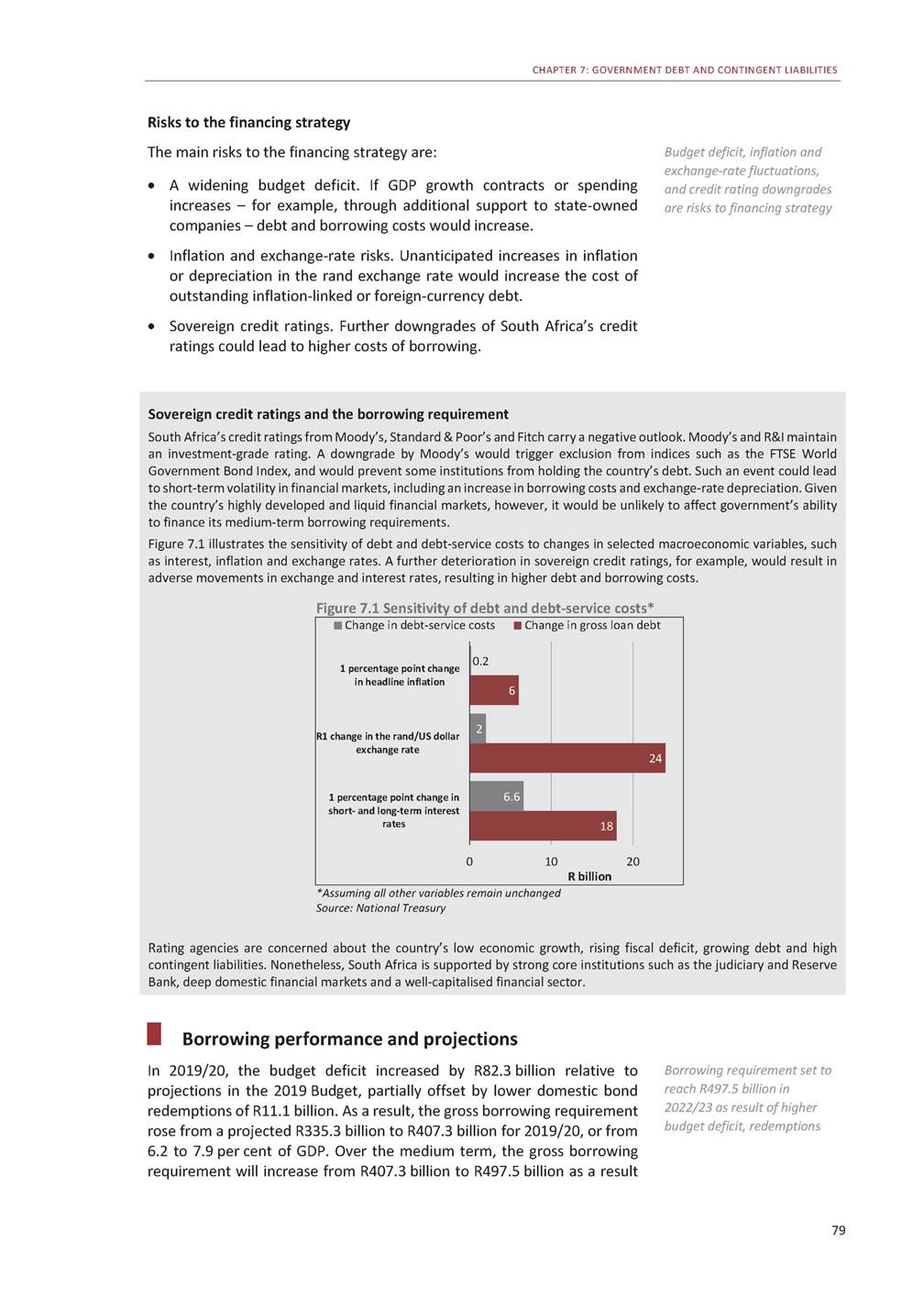

(1) Pages numbered i to v consecutively.

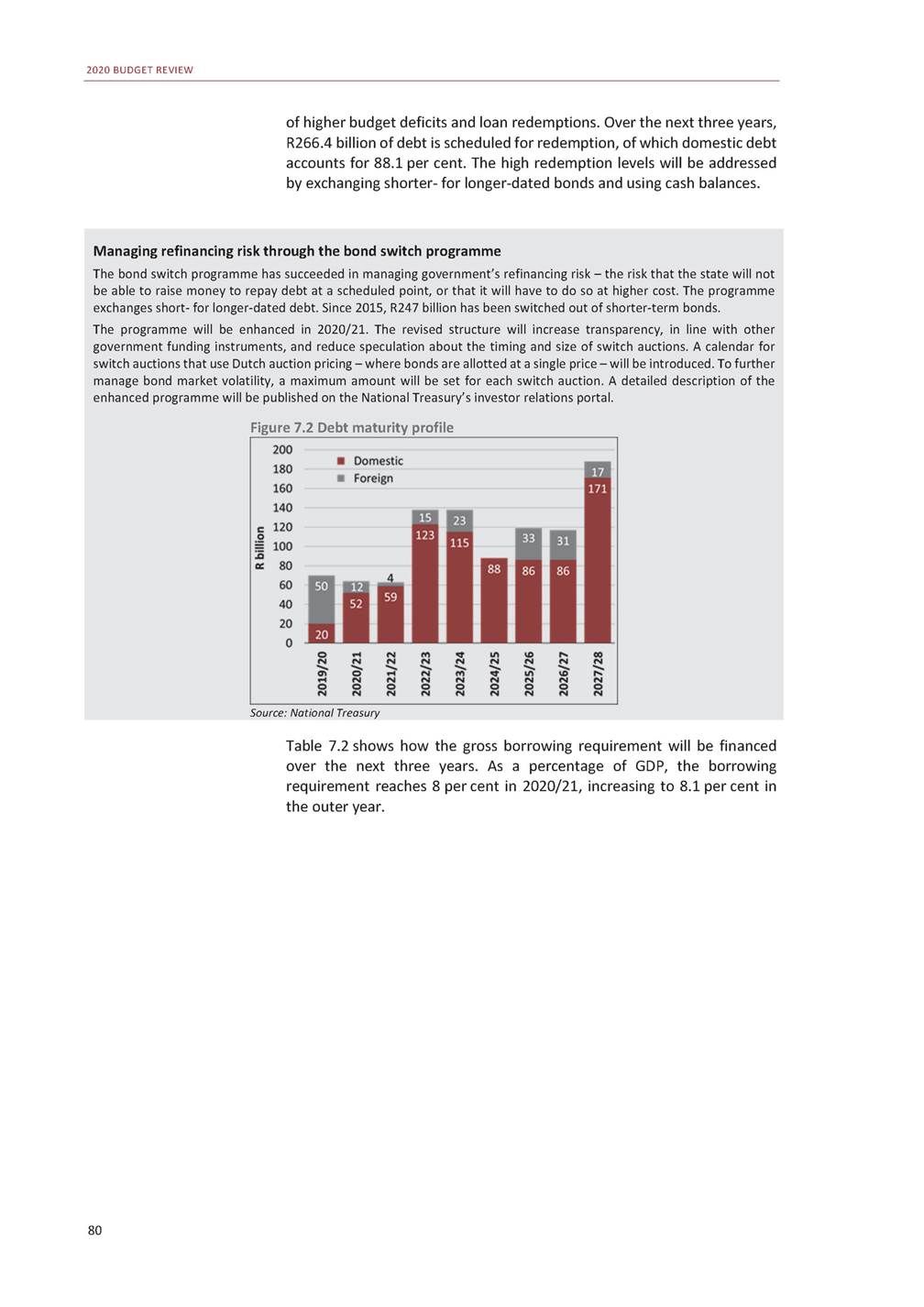

(2) The following exhibits:

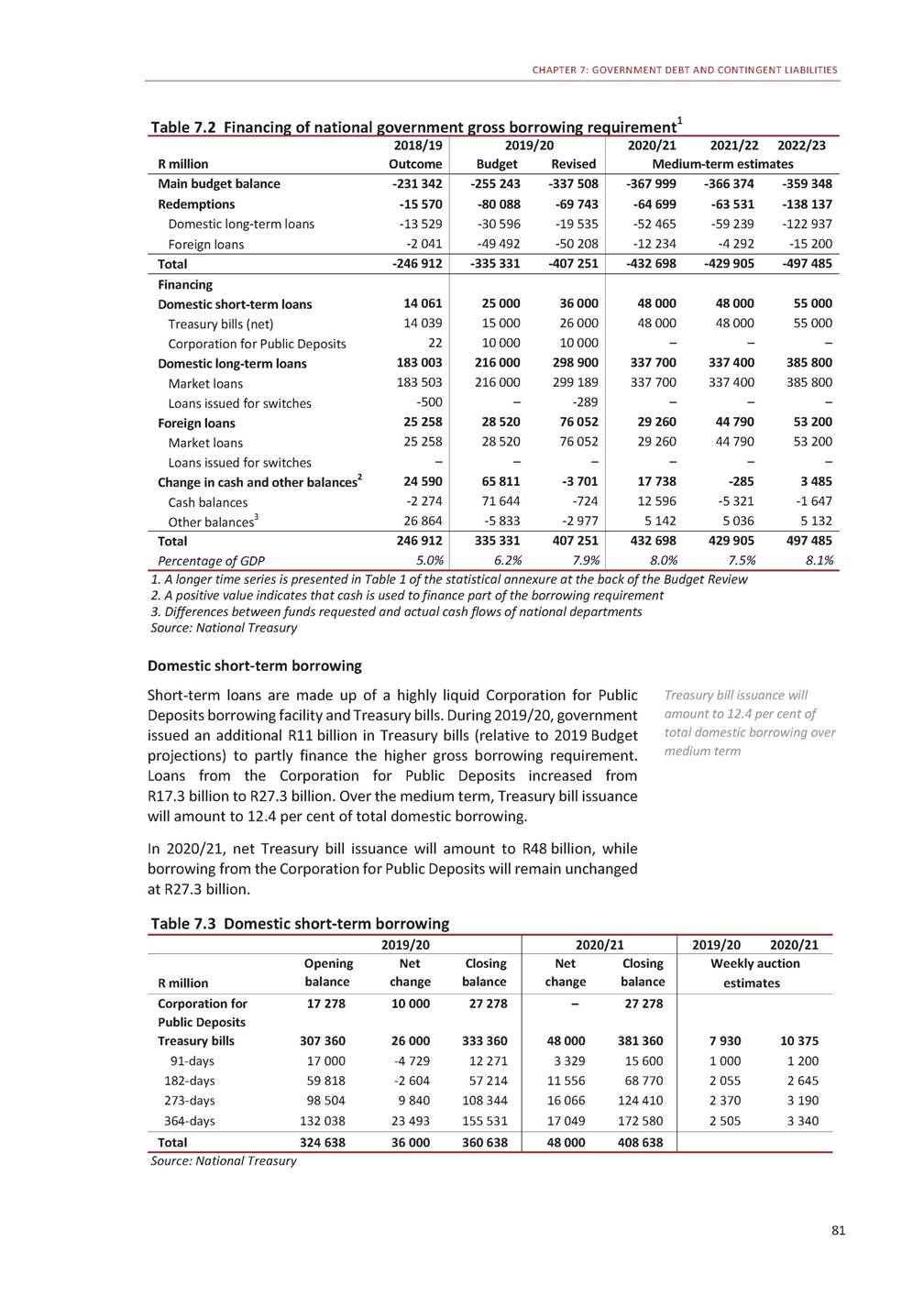

Exhibit A — None.

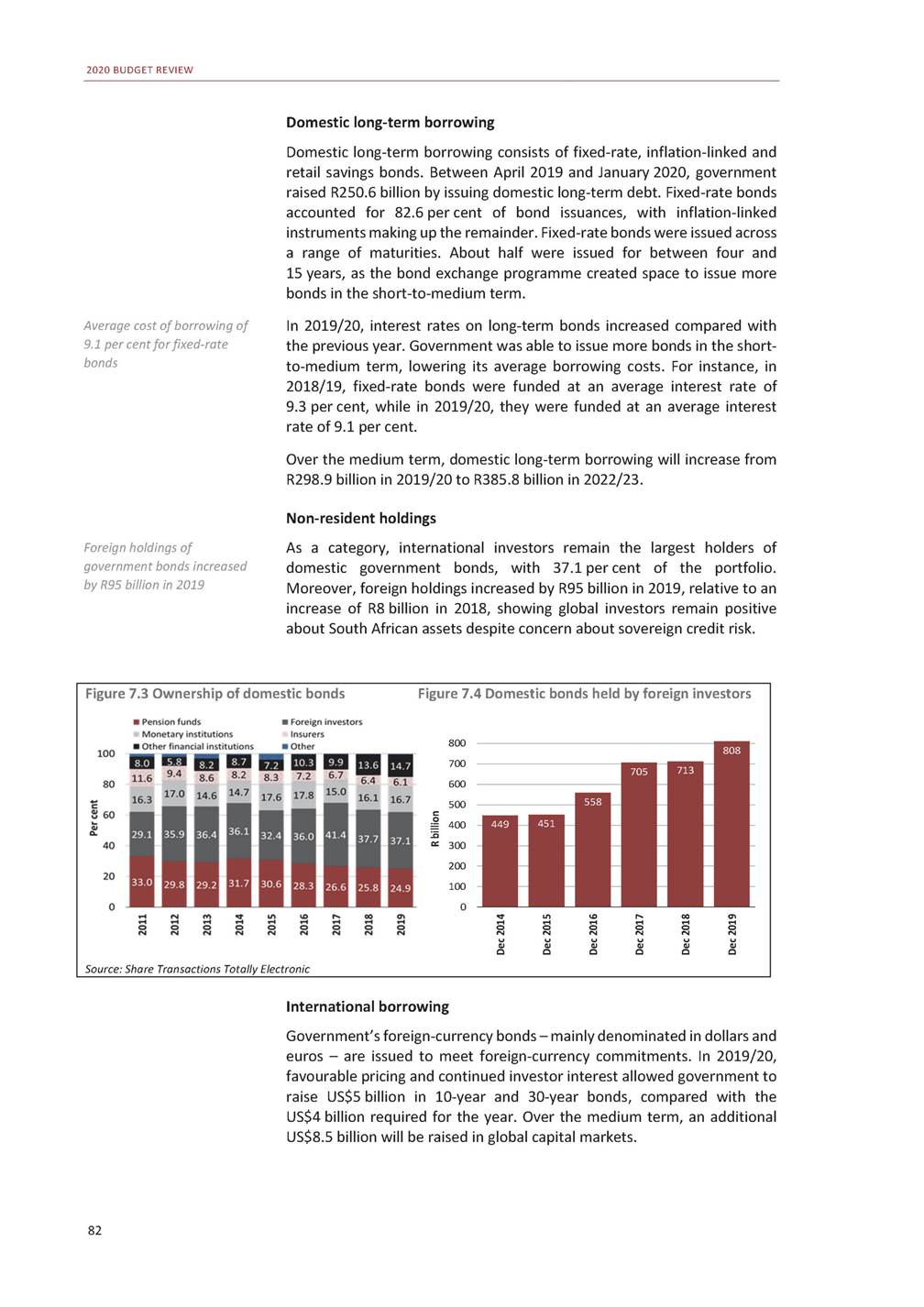

Exhibit B — None.

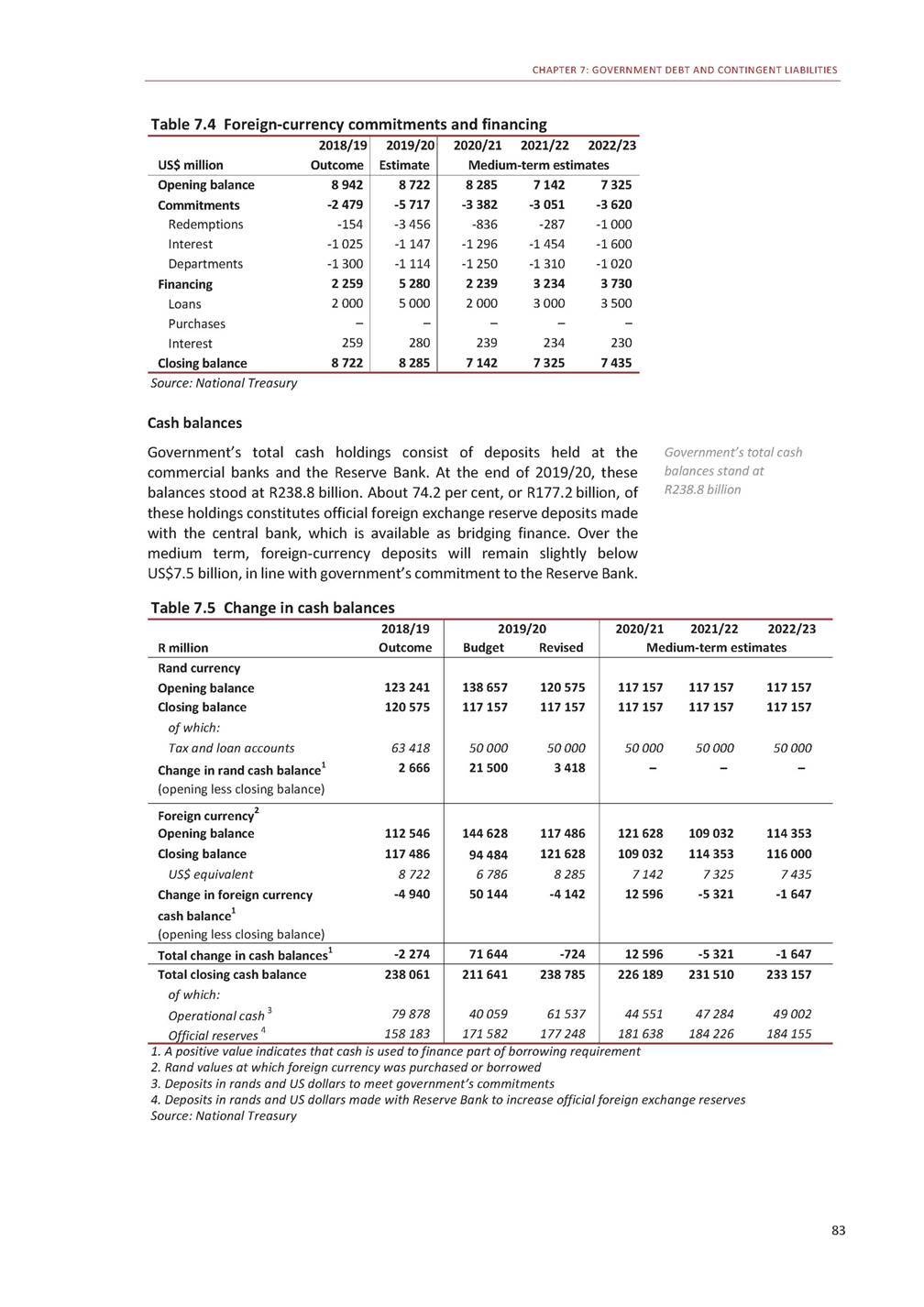

Exhibit 24 — Power of Attorney, dated February 14, 2020.

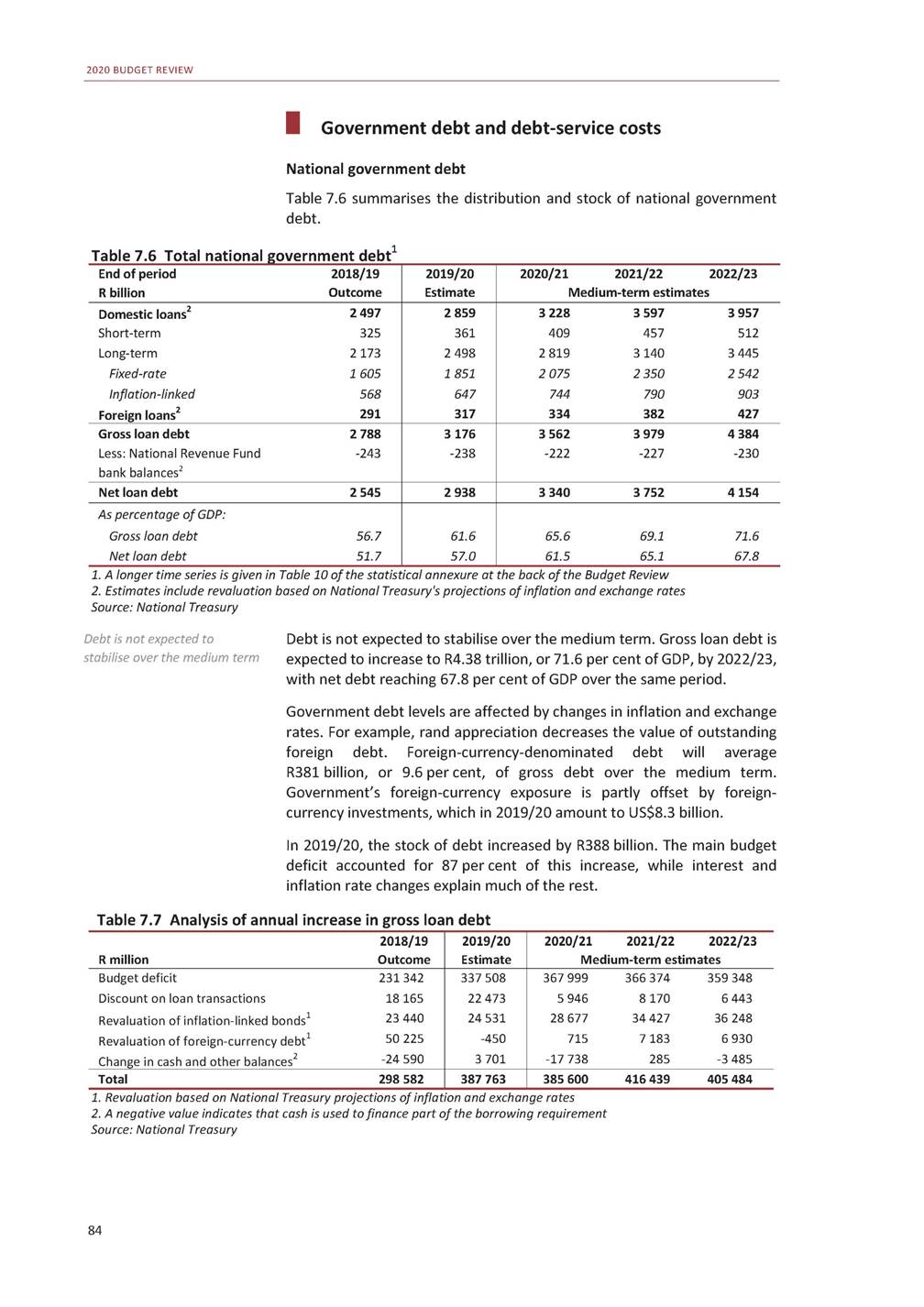

Exhibit 99.C — Republic of South Africa Budget Review 2020.

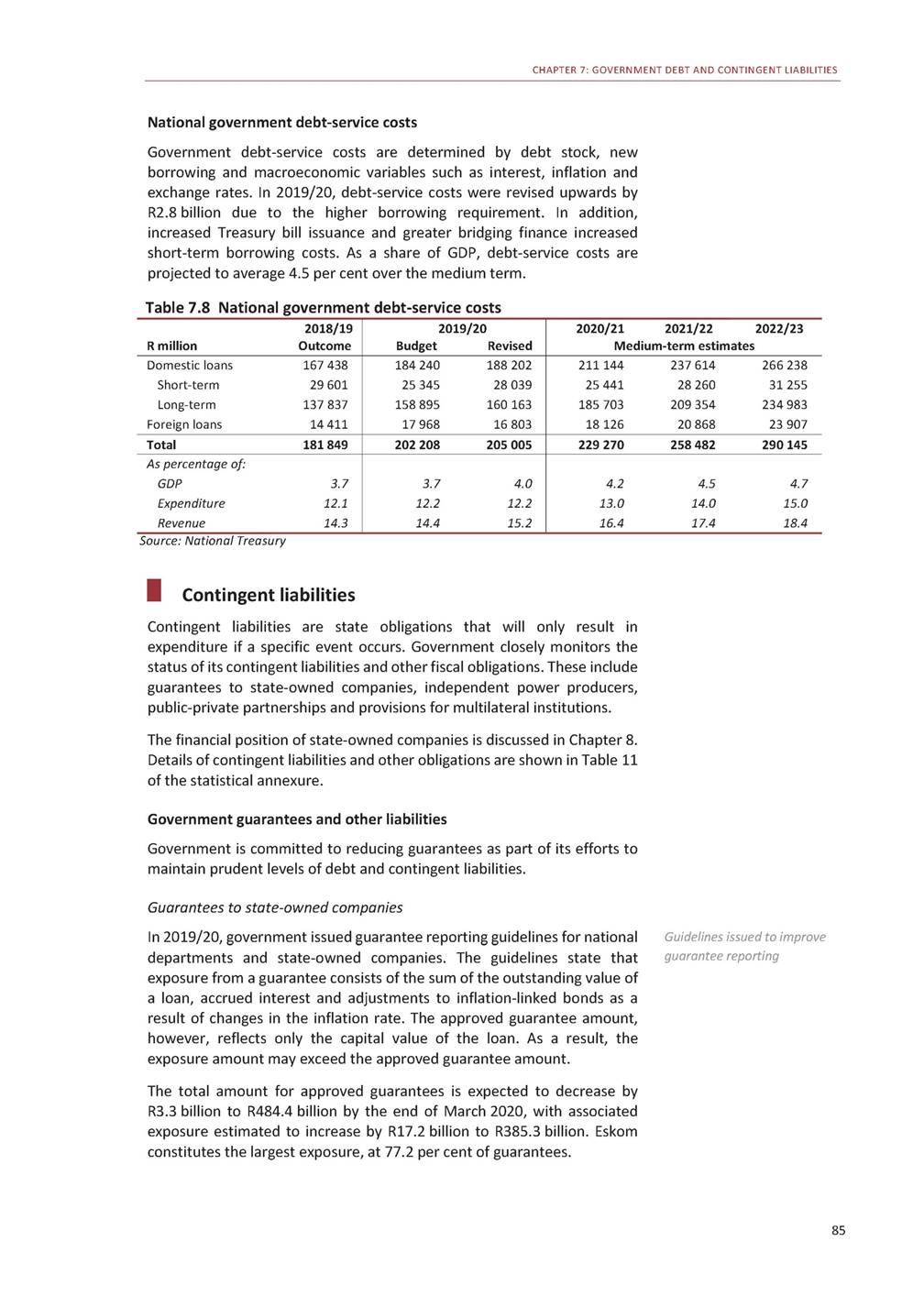

Exhibit 99.D — Republic of South Africa Medium Term Budget Policy Statement 2019.

Exhibit 99.E — Description of the Republic of South Africa dated March 19, 2020.

Exhibit 99.F — Quarterly Bulletin No. 294 dated December 2019, published by the South African Reserve Bank.

This annual report is filed subject to the Instructions for Form 18-K for Foreign Governments and Political Subdivisions thereof.

SIGNATURE

Pursuant to the requirements of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, the Registrant, Republic of South Africa, has duly caused this annual report to be signed on its behalf by the undersigned, thereunto duly authorized, in Pretoria, South Africa, on March 19, 2020.

|

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA |

| |

|

|

| |

|

By: |

/s/ Siyabonga Shange |

|

|

|

Attorney-in-fact for |

|

|

|

TT Mboweni |

|

|

|

Minister of Finance |

|

|

|

Republic of South Africa |

|

EXHIBIT INDEX

POWER OF ATTORNEY

KNOW ALL PERSONS BY THESE PRESENTS, that the undersigned Minister of Finance of the Republic of South Africa (the “Republic”), by his execution hereof, does hereby constitute and appoint Dondo Mogajane, Tshepiso Moahloli and Siyabonga Shange or any of them acting individually as his true and lawful attorney-in-fact and agent, for him and in his name, place and stead, to execute and deliver the Republic’s Annual Report on Form 18-K (the “Form 18-K”) for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2019 and all amendments thereto, as fully to all intents and purposes as the undersigned might or could do in person, hereby ratifying and confirming all the acts of said attorney-in-fact and agent which he may lawfully do or cause to be done by virtue hereof;

PROVIDED THAT, this Power of Attorney shall not constitute a delegation of the Minister of Finance’s powers to borrow money on behalf of the Republic in terms of section 72 of the Public Finance Management Act, 1999, as amended.

|

Dated: 14 February 2020 |

By: |

/s/ TT Mboweni |

|

|

|

TT Mboweni |

|

|

|

Minister of Finance |

|

|

|

Republic of South Africa |

ISBN: RP: 9780621481013 19/2020 The Budget Review is compiled using the latest available information from departmental and other sources. Some of this information is unaudited or subject to revision. To obtain additional copies of this document, please contact: Communications Directorate National Treasury Private Bag X115 Pretoria 0001 South Africa Tel: +27 12 315 5944 Fax: +27 12 407 9055 The document is also available on the internet at: www.treasury.gov.za. ii

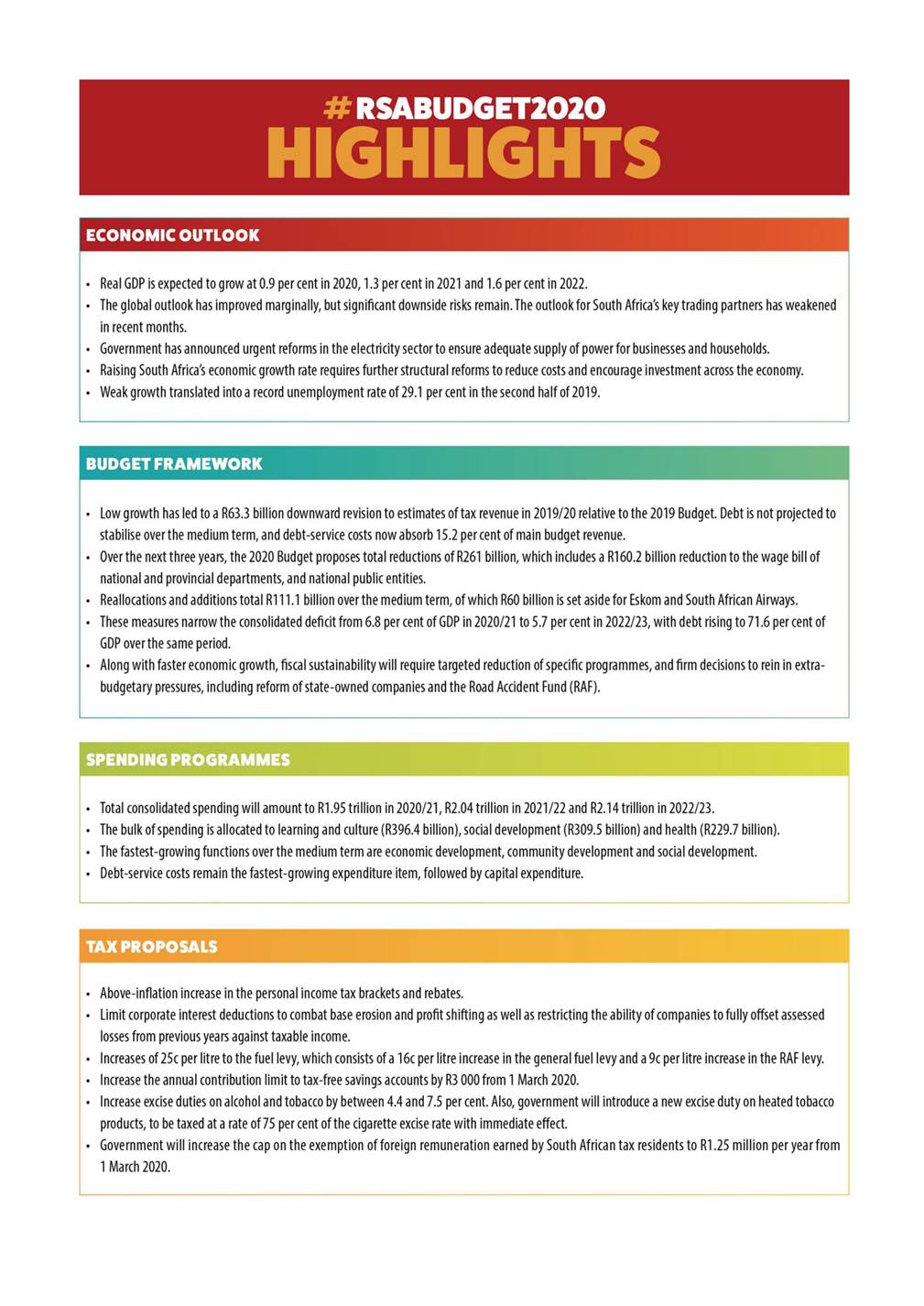

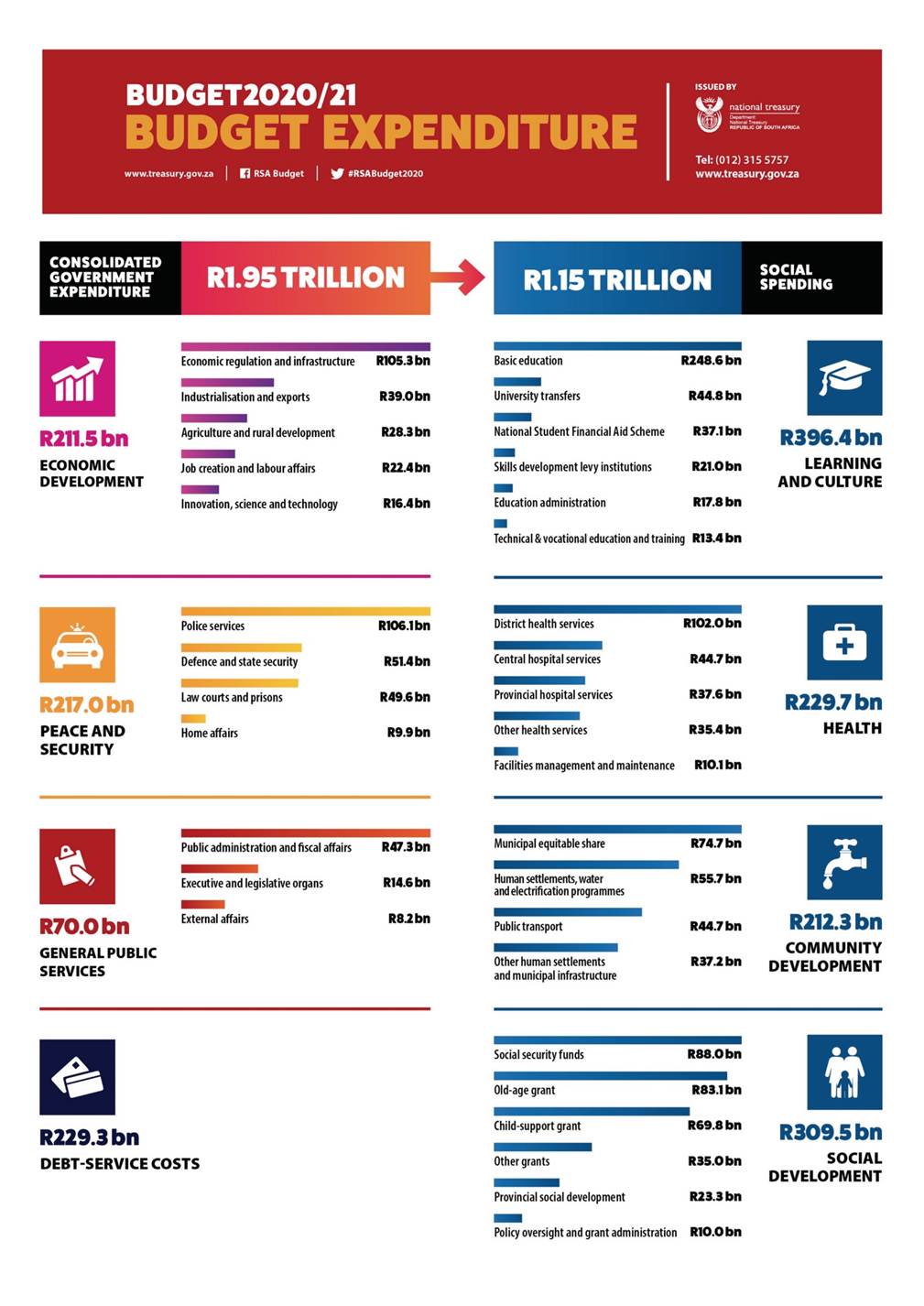

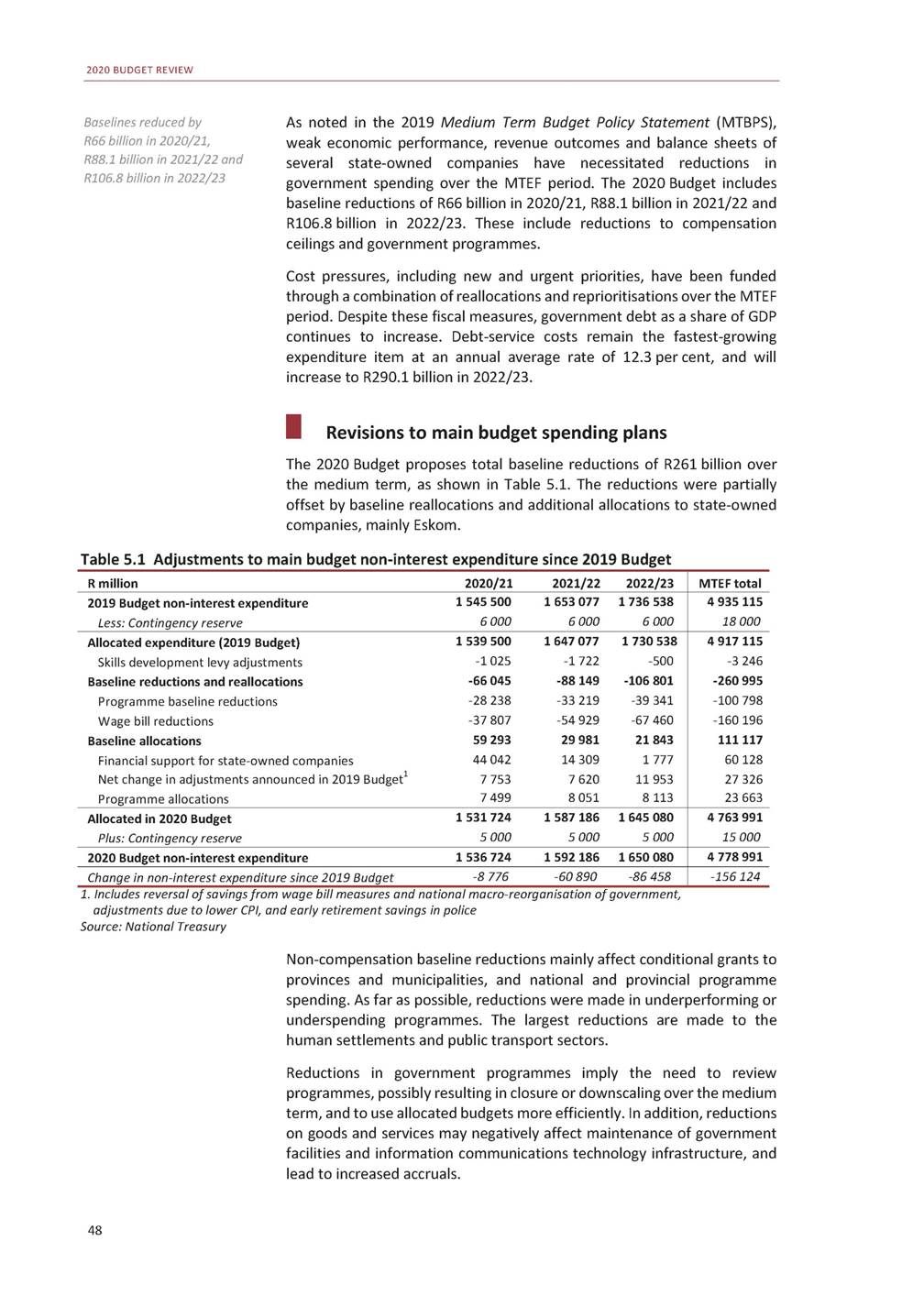

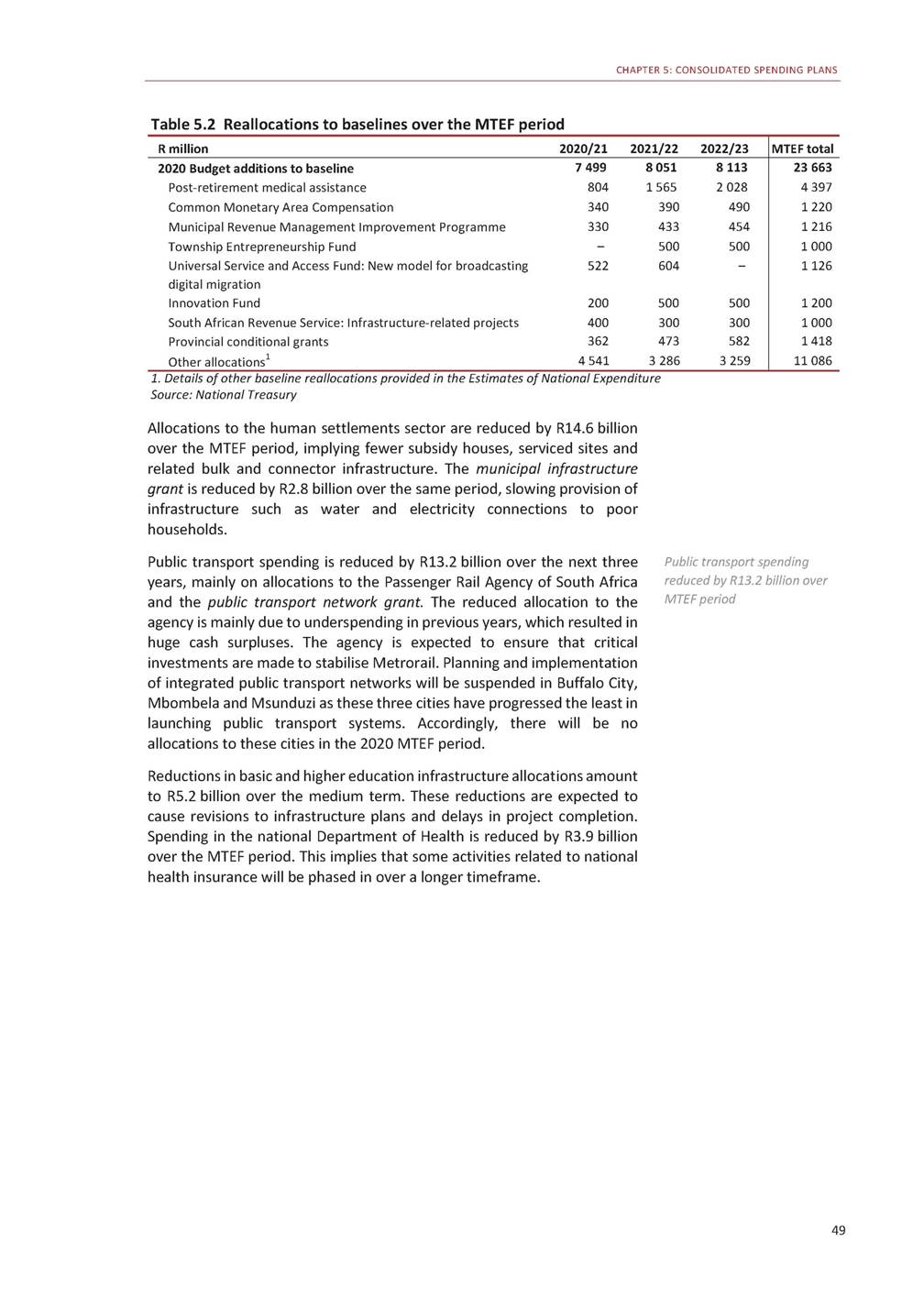

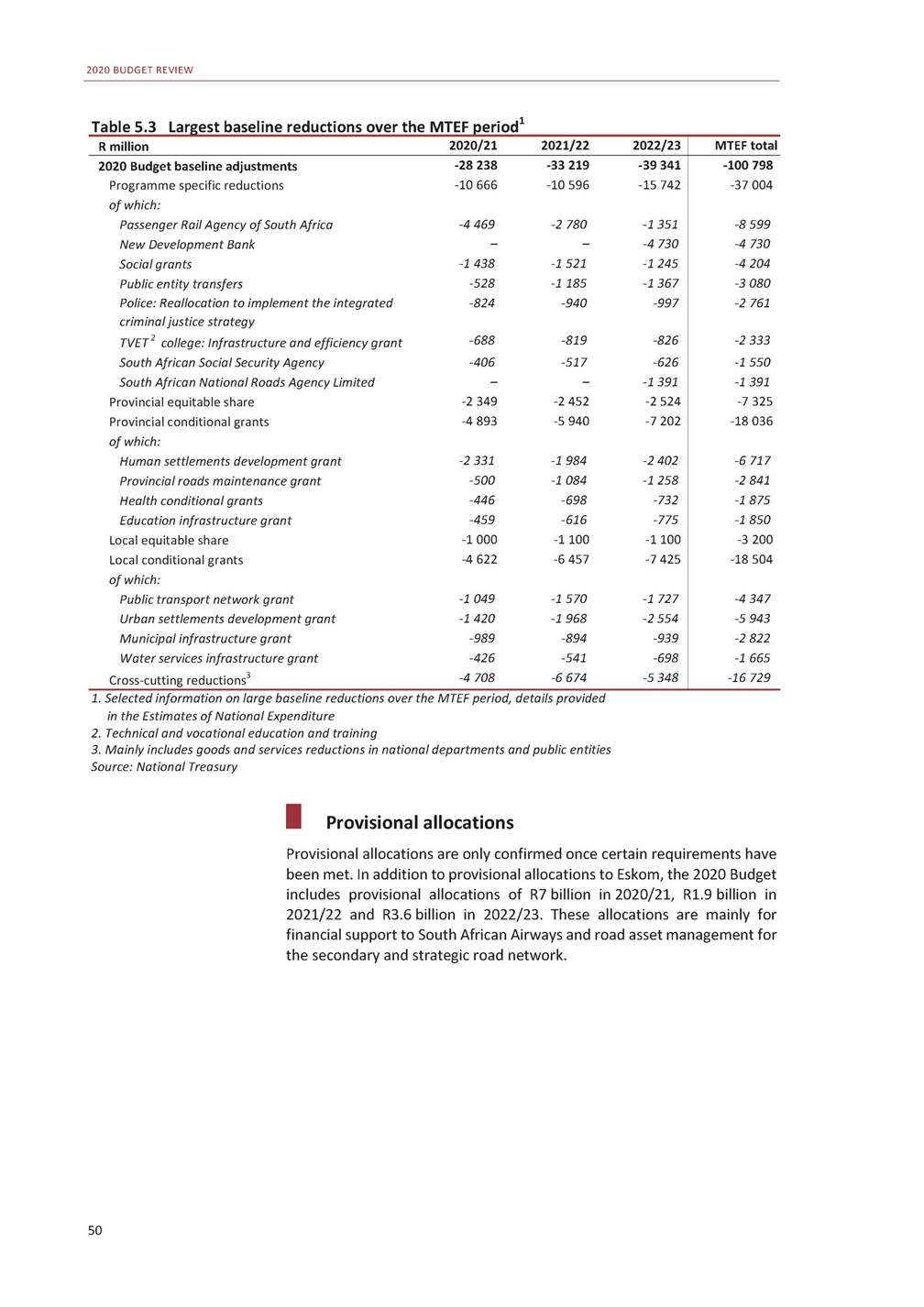

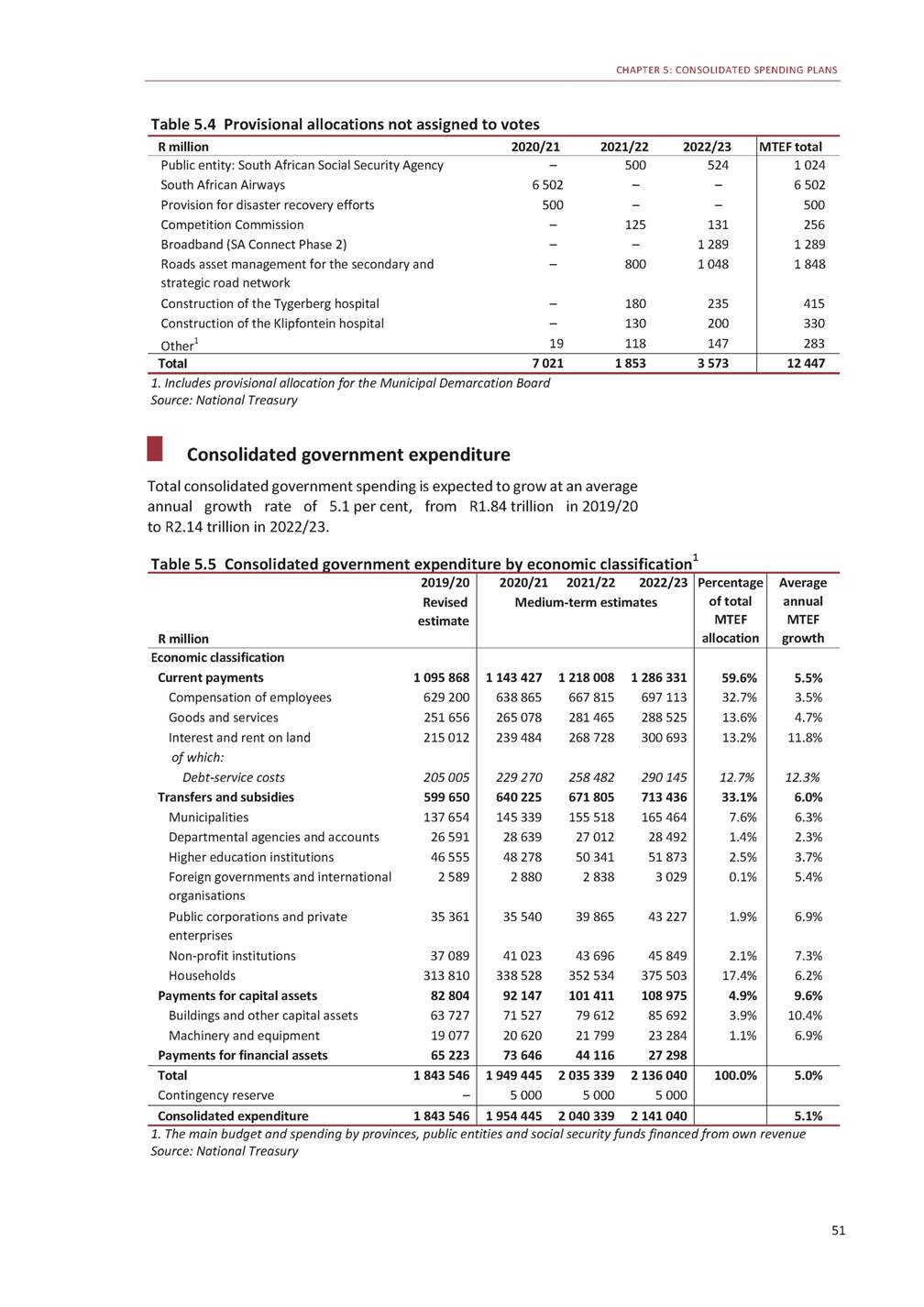

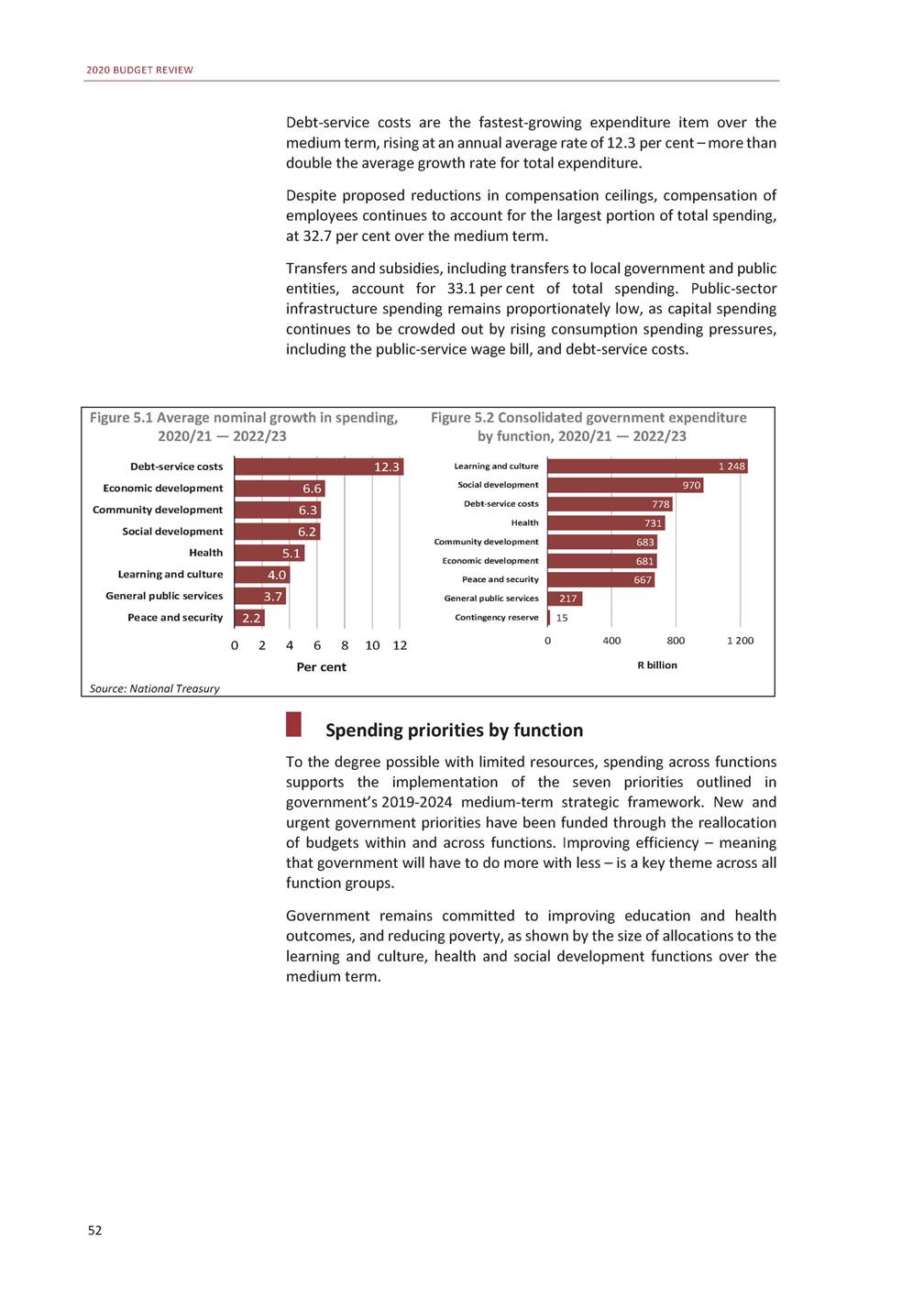

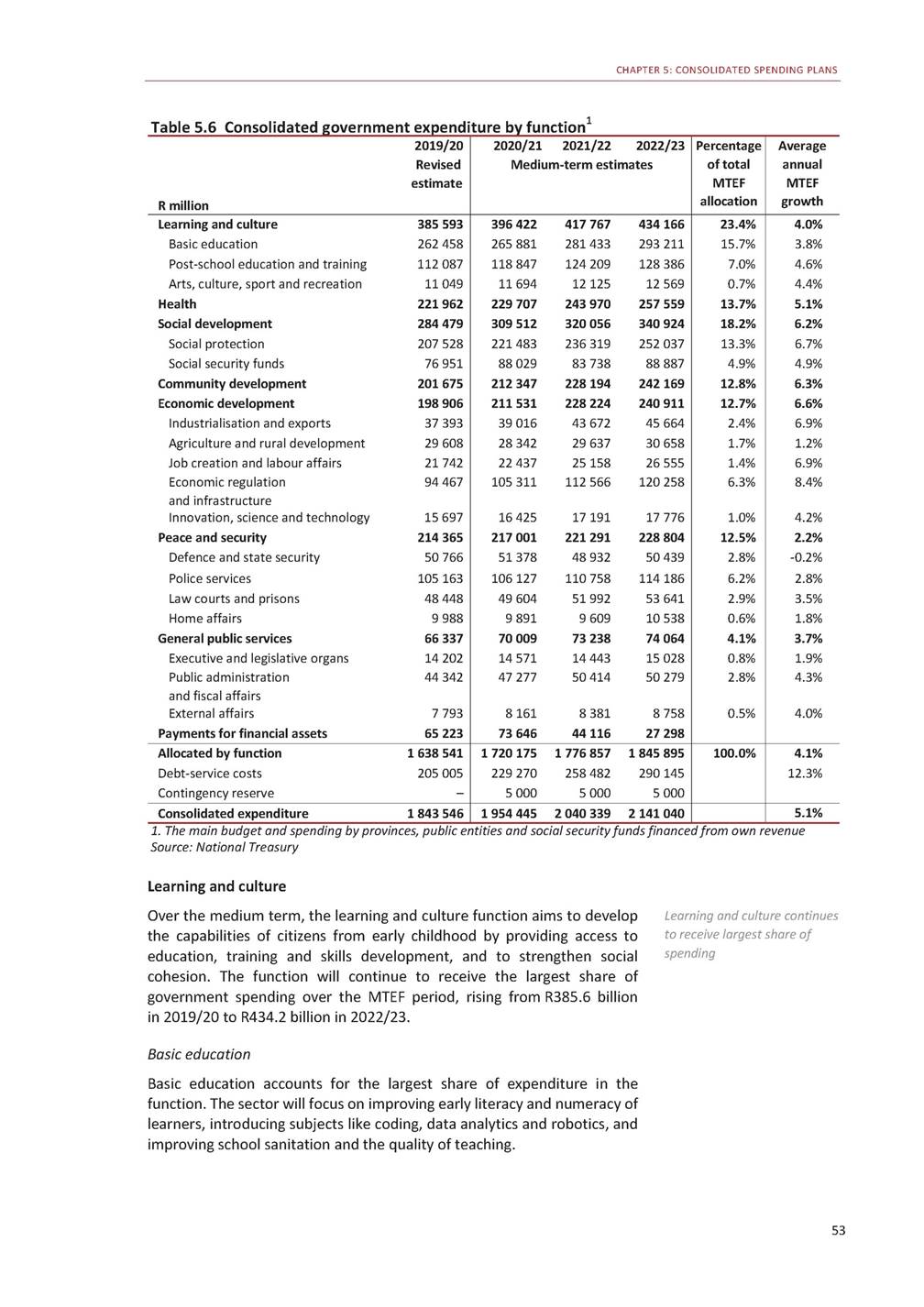

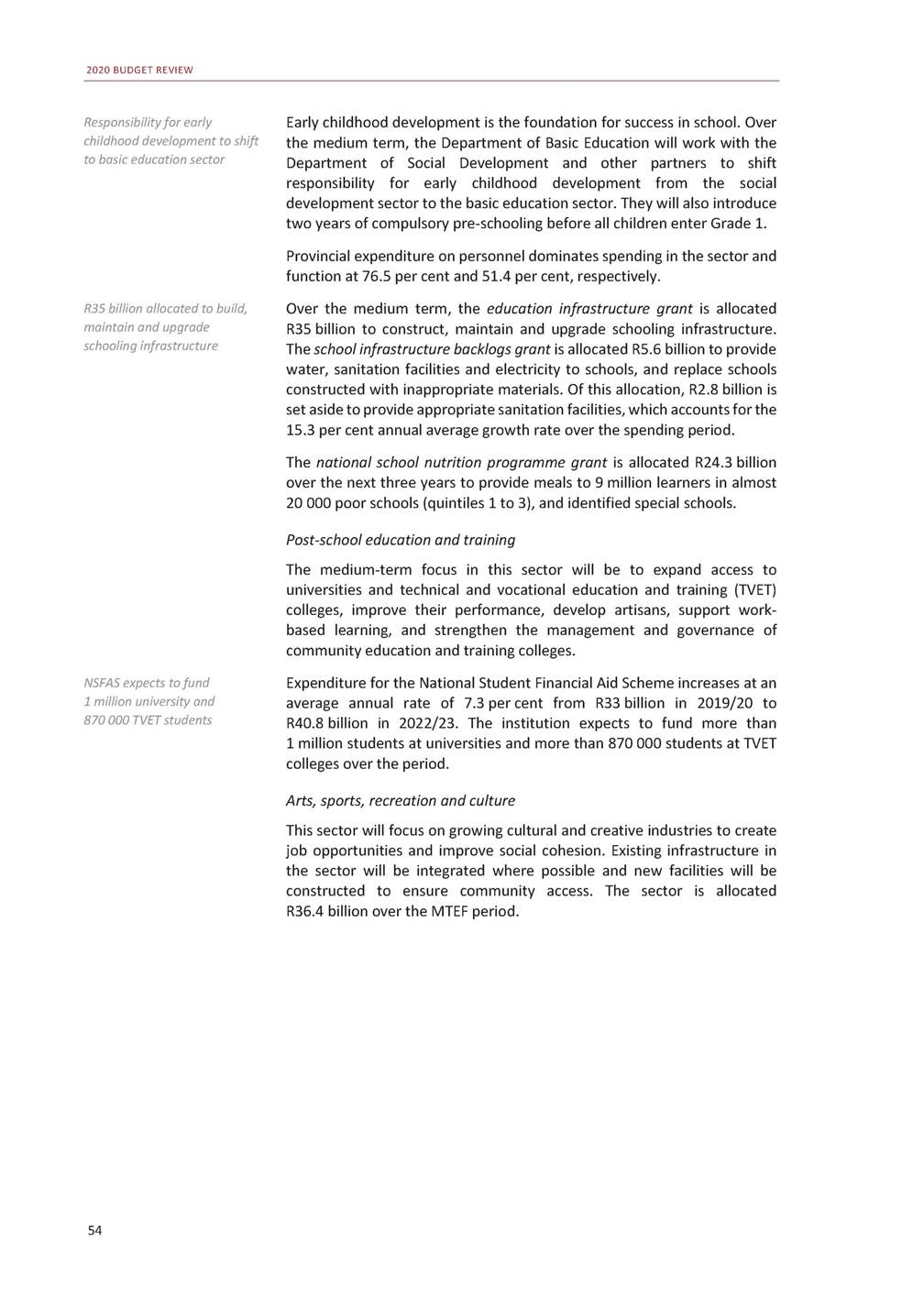

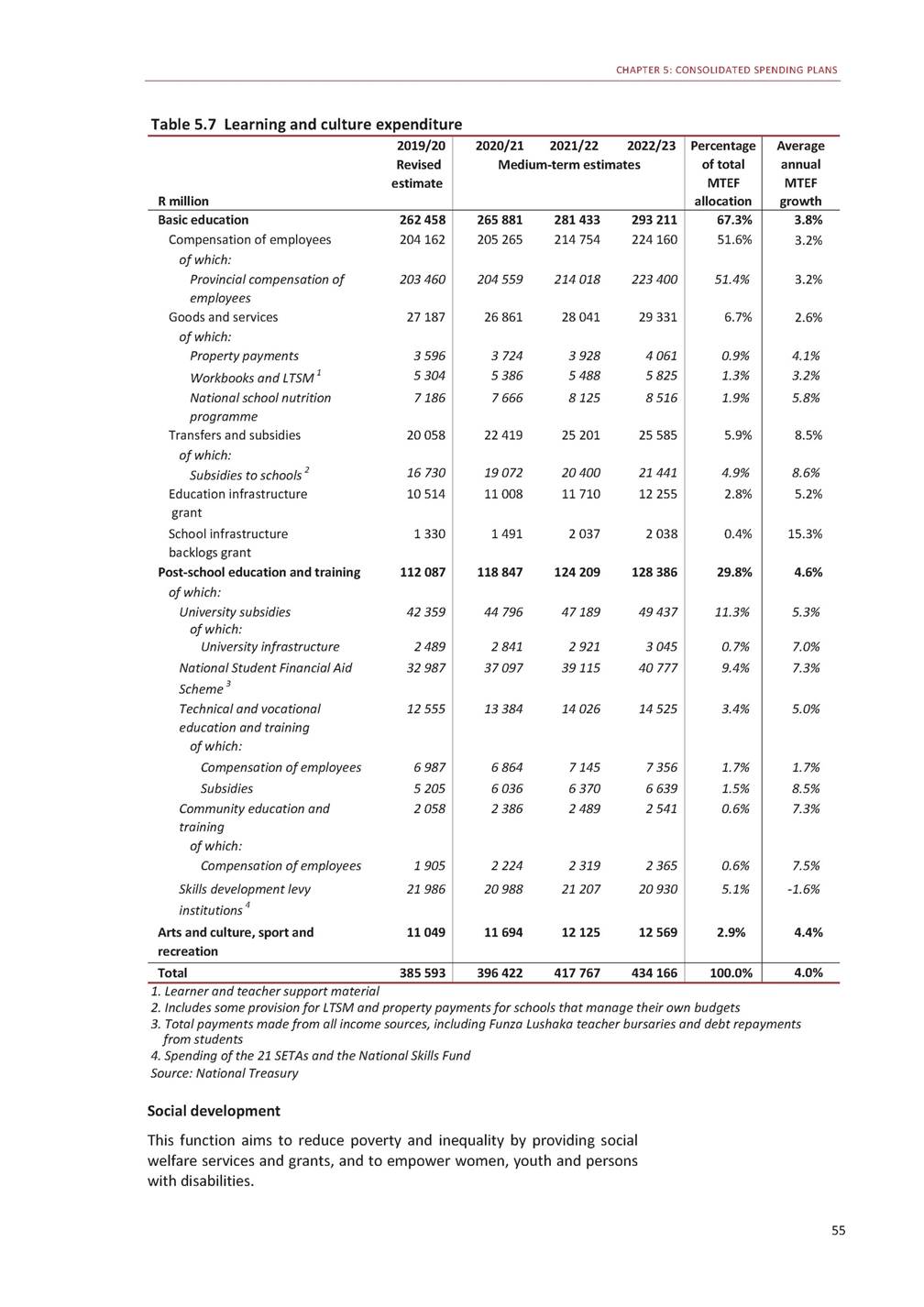

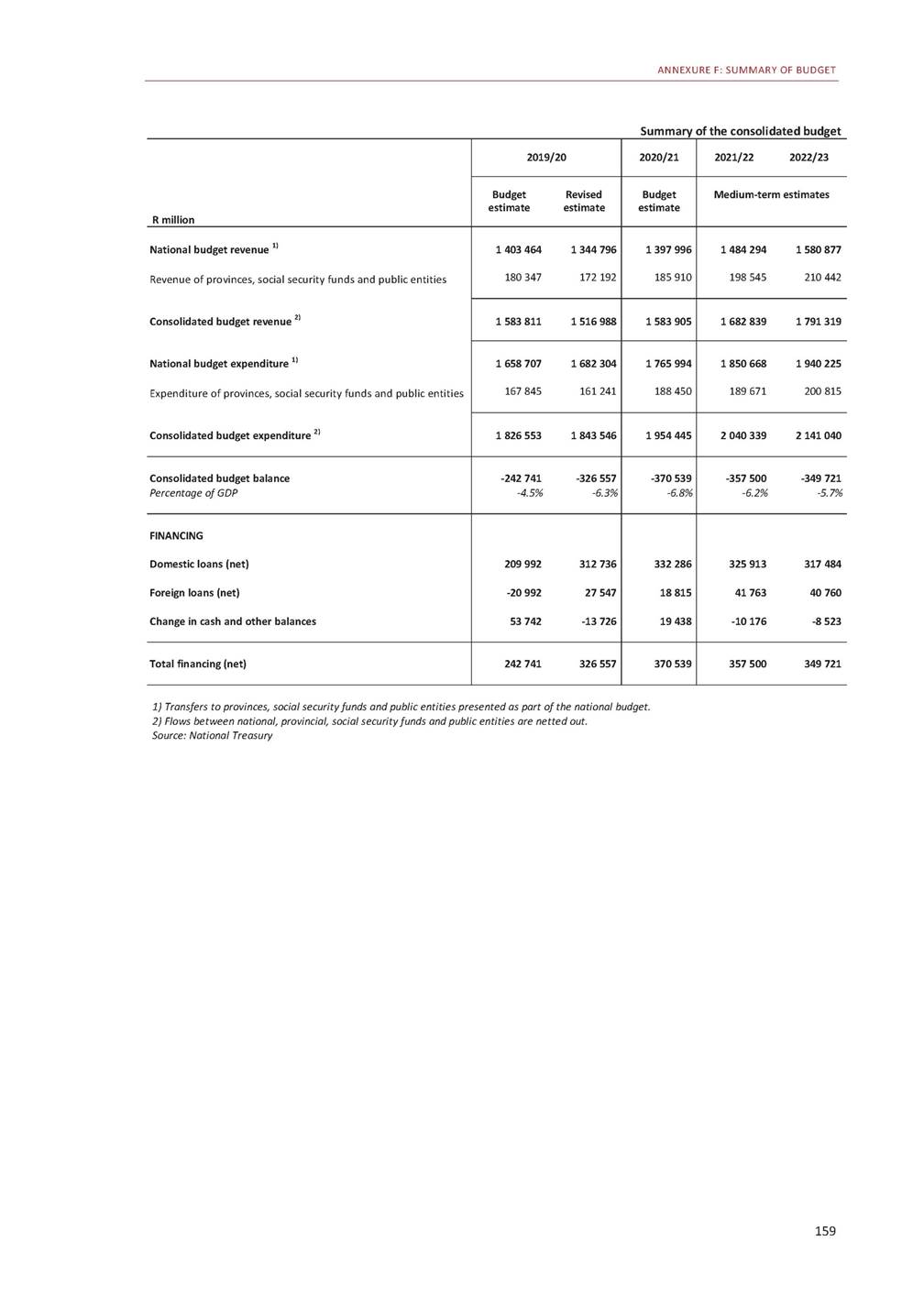

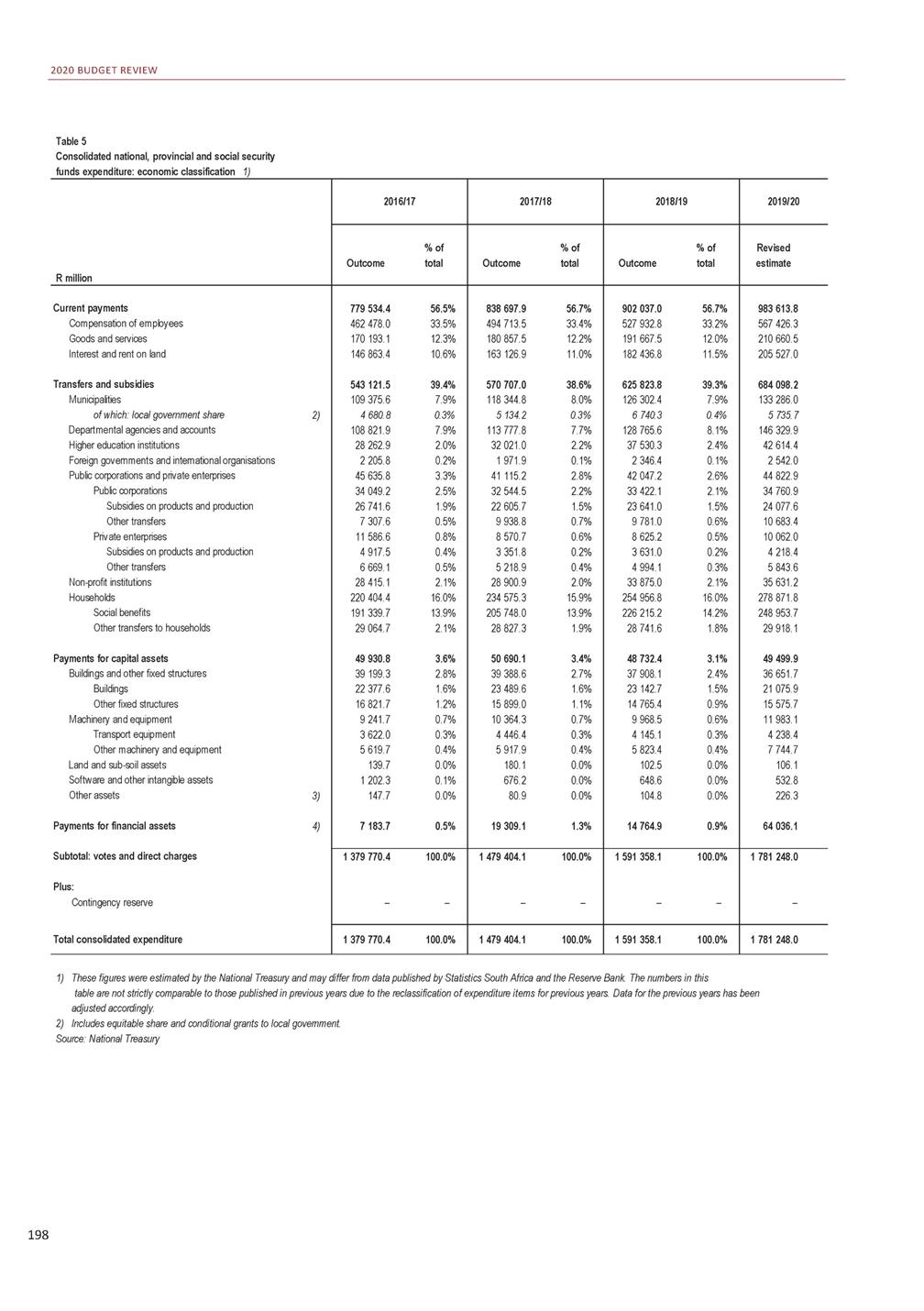

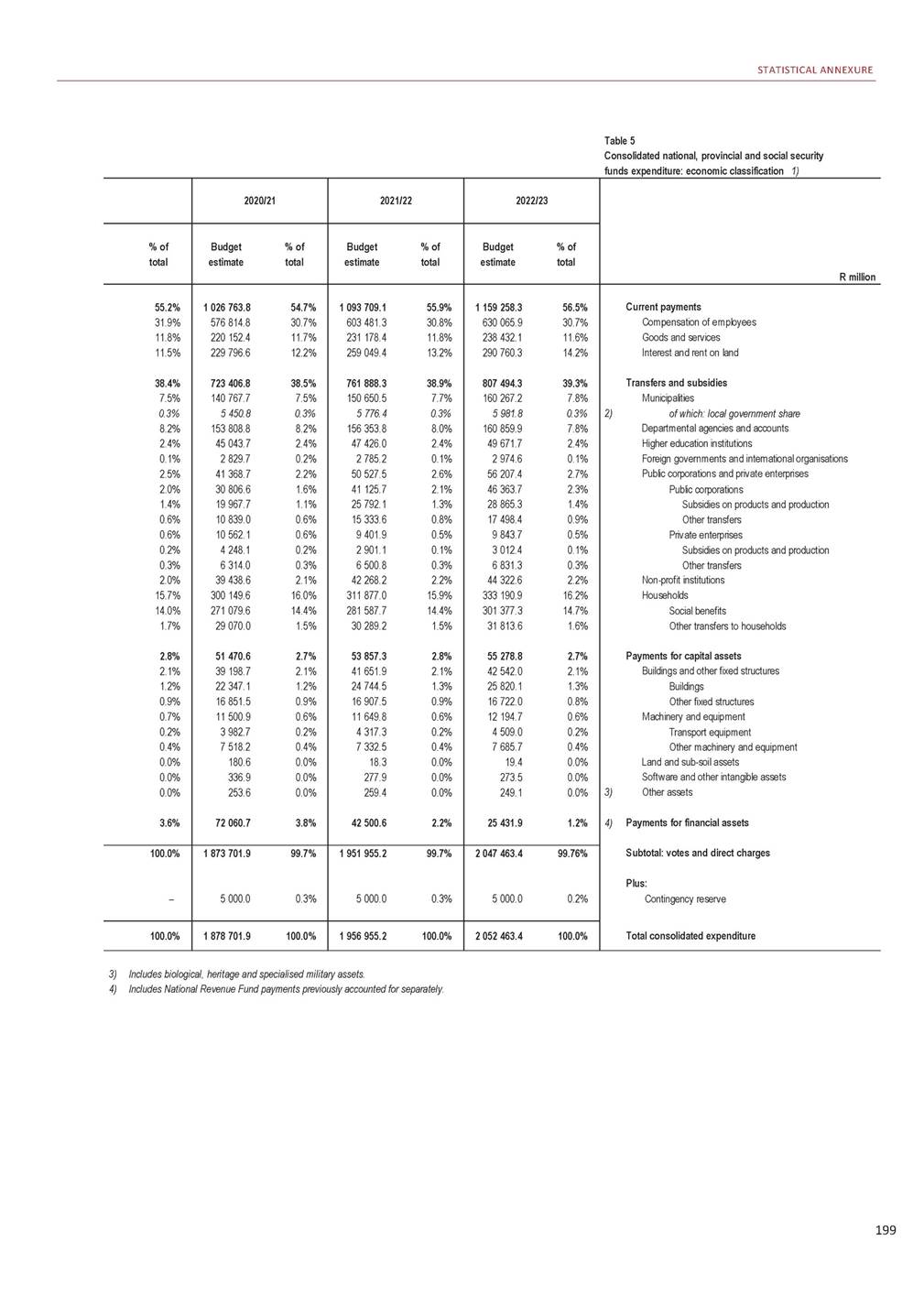

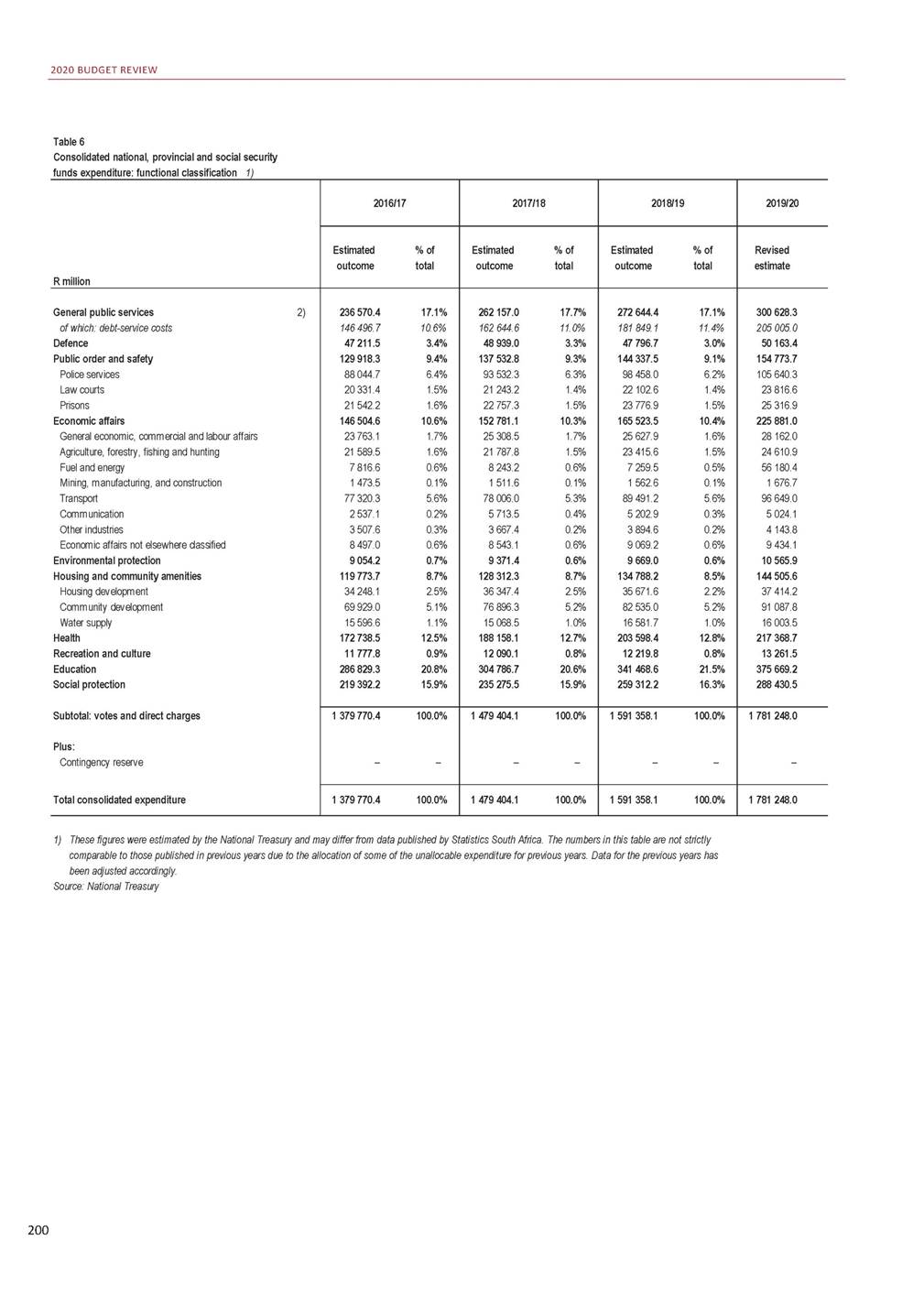

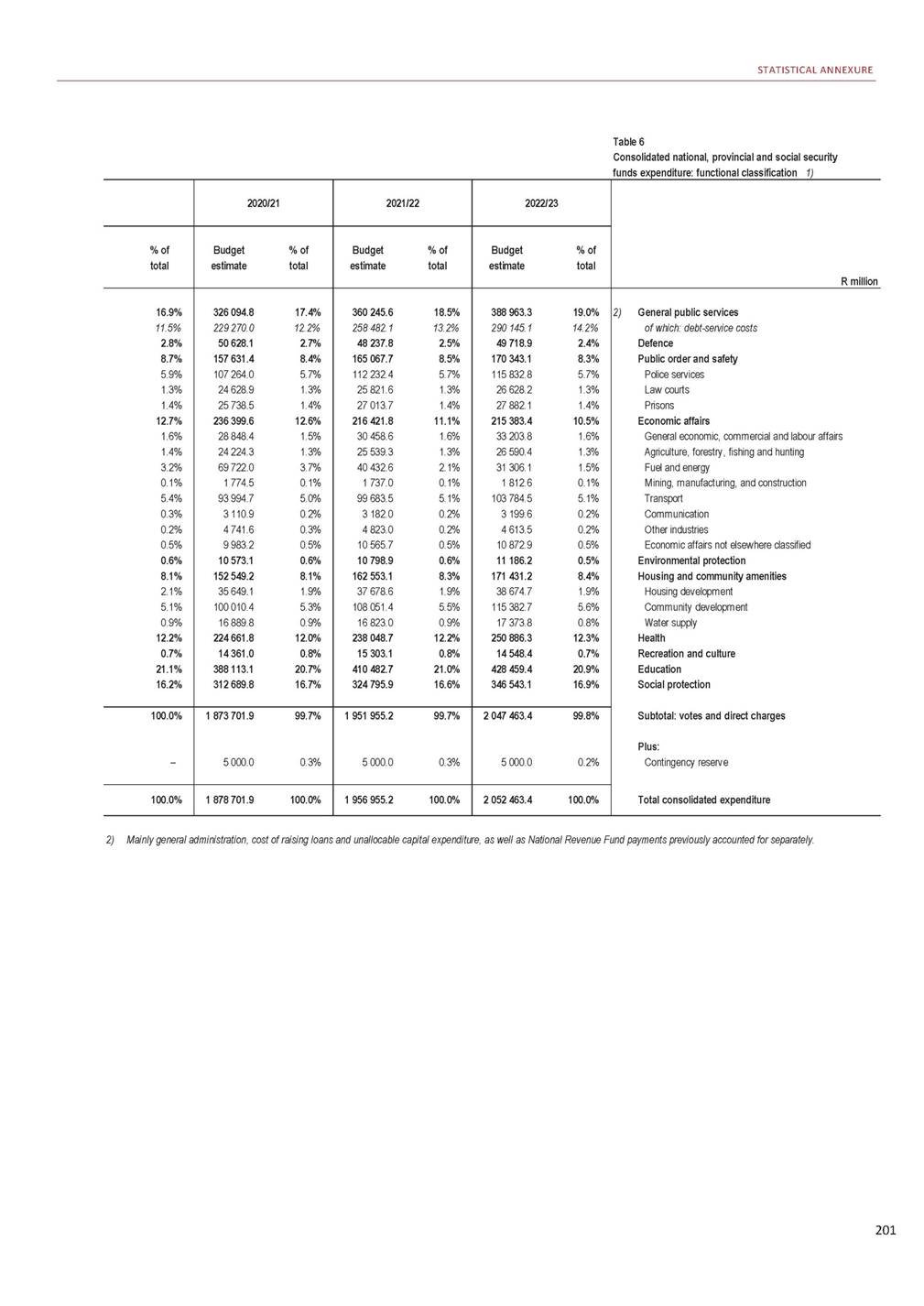

# HIGHLIGHTS Total consolidated spending willamount to R1.95 trillion in 2020/21,R2.04 trillion in 2021/22 and R2.14 trillion in 2022/23. The bulk of spending is allocated to learning and culture (R396.4 billion),socialdevelopment (R309.5 billion) and health (R229.7 billion). The fastest-growing functions over the medium term are economic development,community development and socialdevelopment. Debt-service costs remain the fastest-growing expenditure item,followed by capitalexpenditure. • • Above-inflation increase in the personalincome tax brackets and rebates. Limit corporate interest deductions to combat base erosion and profit shifting as well as restricting the ability of companies to fully offset assessed losses from previous years against taxable income. Increases of 25c per litre to the fuellevy,which consists of a 16c per litre increase in the generalfuel levy and a 9c per litre increase in the RAF levy. Increase the annualcontribution limit to tax-free savings accounts by R3 000 from 1 March 2020. Increase excise duties on alcoholand tobacco by between 4.4 and 7.5 per cent. Also,government will introduce a new excise duty on heated tobacco products,to be taxed at a rate of75 per cent of the cigarette excise rate with immediate effect. Government will increase the cap on the exemption of foreign remuneration earned by South African tax residents to R1.25 million per year from 1 March 2020. • • TAX PROPOSALS SPENDING PROGRAMMES • Low growth has led to a R63.3 billion downward revision to estimates of tax revenue in 2019/20 relative to the 2019 Budget. Debt is not projected to stabilise over the medium term,and debt-service costs now absorb 15.2 per cent of main budget revenue. Over the next three years,the 2020 Budget proposes total reductions of R261 billion,which includes a R160.2 billion reduction to the wage bill of nationaland provincialdepartments,and nationalpublic entities. Reallocations and additions totalR111.1 billion over the medium term,of which R60 billion is set aside for Eskom and South African Airways. • These measures narrow the consolidated deficit from 6.8 per cent of GOP in 2020/21 to 5.7 per cent in 2022/23, with debt rising to 71.6 per cent of GOP over the same period. • Along with faster economic growth,fiscalsustainability will require targeted reduction of specific programmes,and firm decisions to rein in extra budgetary pressures,including reform of state-owned companies and the Road Accident Fund (RAF). BUDGET FRAMEWORK • RealGOP is expected to grow at 0.9 per cent in 2020,1.3 per cent in 2021 and 1.6 per cent in 2022. The global outlook has improved marginally,but significant downside risks remain.The outlook for South Africa's key trading partners has weakened in recent months. Government has announced urgent reforms in the electricity sector to ensure adequate supply of power for businesses and households. • Raising South Africa's economic growth rate requires further structuralreforms to reduce costs and encourage investment across the economy. • Weak growth translated into a record unemployment rate of 29.1 per cent in the second half of 2019. ECONOMIC OUTLOOK RSABUDGET2020

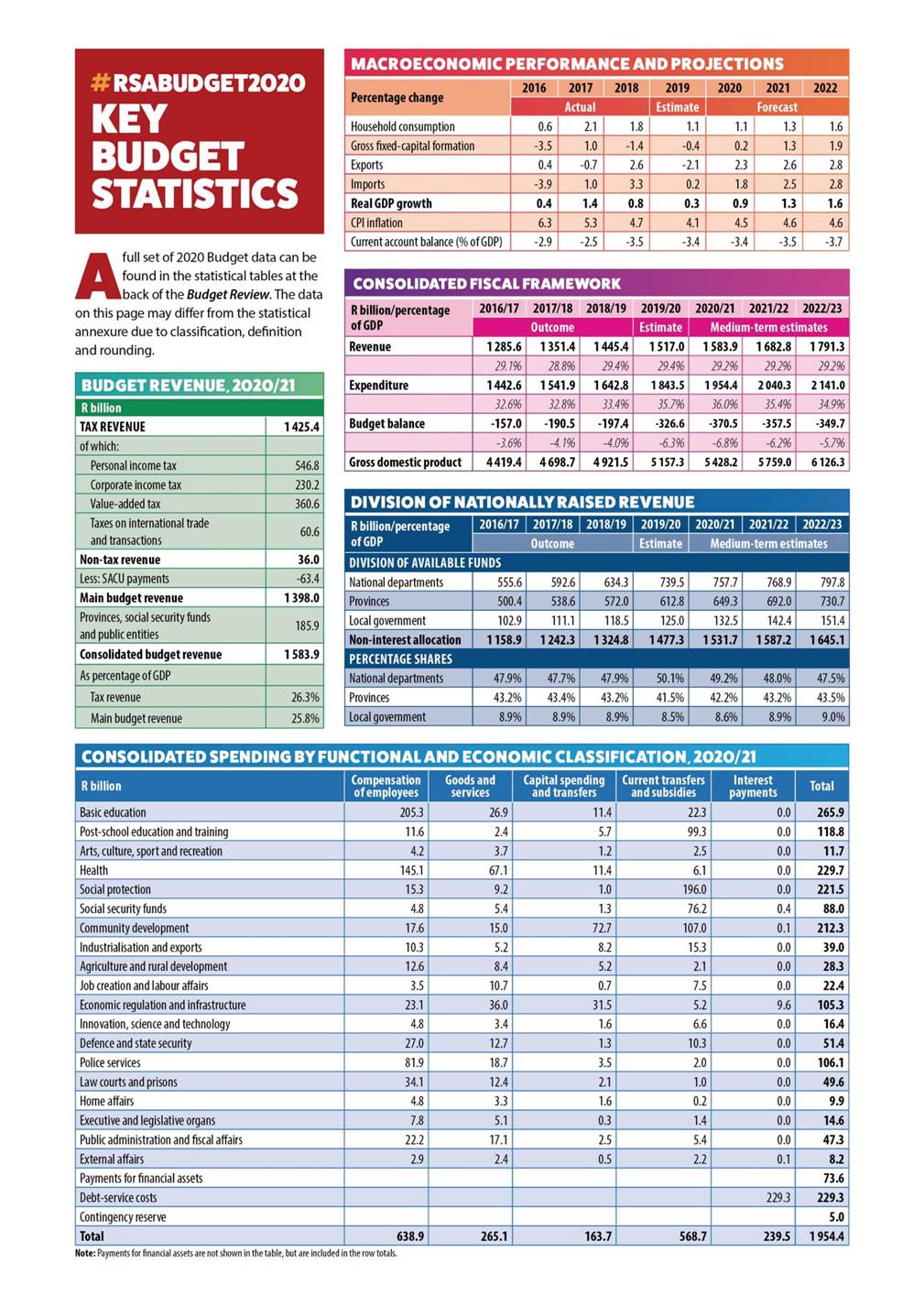

KEY Afull set of 2020 Budget data can be found in the statisticaltables at the back of the Budget Review.The data on this page may differ from the statistical annexure due to classification,definition and rounding. J2ill Note: Paymentsfor financial assets are not shown in the table, but a re included in the row totals. Non-interestallocation 1158.91242.3 1324.8 1477.31531.71587.21645.1 PERCENTAGE SHARES National departments 47.9% 47.7% 47.9% 50.1% 49.2% 48.0% 47.5% Provinces 43.2% 43.4% 43.2% 41.5% 42.2% 43.2% 43.5% Local government 8.9% 8.9% 8.9% 8.5% 8.6% 8.9% 9.0% BUDG ETREV ENUE.2020 R billion TAX REVENUE 1425.4 of which: Personalincome tax 546.8 Corporate income tax 230.2 Value-added tax 360.6 Taxes on international trade and transactions 60.6 Non-tax revenue 36.0 Less:SACU payments -63.4 Main budget revenue 1398.0 Provinces,socialsecurity funds and public entities 185.9 Consolidated budget revenue 1583.9 As percentage of GDP Tax revenue 26.3% Main budget revenue 25.8% # RSABUDGETZOZO BUDGET STATISTICS

ISSUED BY u national treasur =-r__, BUDGET EXPENDITURE • RE IIUCOFSOUTHMRICA I I ON NG a m -Basic education Economic regulation and infrastructure R105.3bn -University transfers R248.6bn Industrialisation and exports R39.0bn R44.8bn -National Student Financial Aid Scheme Agriculture and rural development R37.1bn R28.3bn RZ11.5bn ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT R396.4bn LEARNING AND CULTURE - - Skills development levy institutions R21.0bn Job creation and labour affairs R22.4bn -Education administration Innovation, science and technology R17.8bn R16.4bn Technical & vocational education and training R13.4bn m B District health services R102.0bn Police services R106.1bn • Central hospital services R44.7bn Defence and state security R51.4bn Provincial hospital services R37.6bn law courts and prisons - R49.6bn RZZ9.7bn RZ17.0bn PEACE AND SECURITY HEALTH Other health services R35.4bn Home affairs R9.9bn Facilities management and maintenanceR10.1bn Municipal equitable share R74.7bn Public administration and fiscal affairs R47.3bn - Humansettlements,water and electrification programmes RSS.7bn Executive and legislative organs R14.6bn External affairs R8.2bn RZ12.3bn COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT R70.0bn GENERAL PUBLIC SERVICES Public transport R44.7bn Other human settlements and municipal infrastructure R37.2bn 13 I! Social security funds R88.0bn Old-age grant R83.1bn Child-support grant R69.8bn R309.5bn SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT RZZ9.3bn DEBT-SERVICE COSTS Other grants R3S.Obn -Provincial social development R23.3bn Policy oversight and grant administration RlO.Obn R1.15TRILLION R1.95 TRILI CONSOLIDATED GOVERNMENT EXPENDITURE www.treasury.gov.za W #RSABudget2020 11 RSA Budget Tel:(012) 315 5757 www.treasury.gov.za BUDGET2020/21

[LOGO]

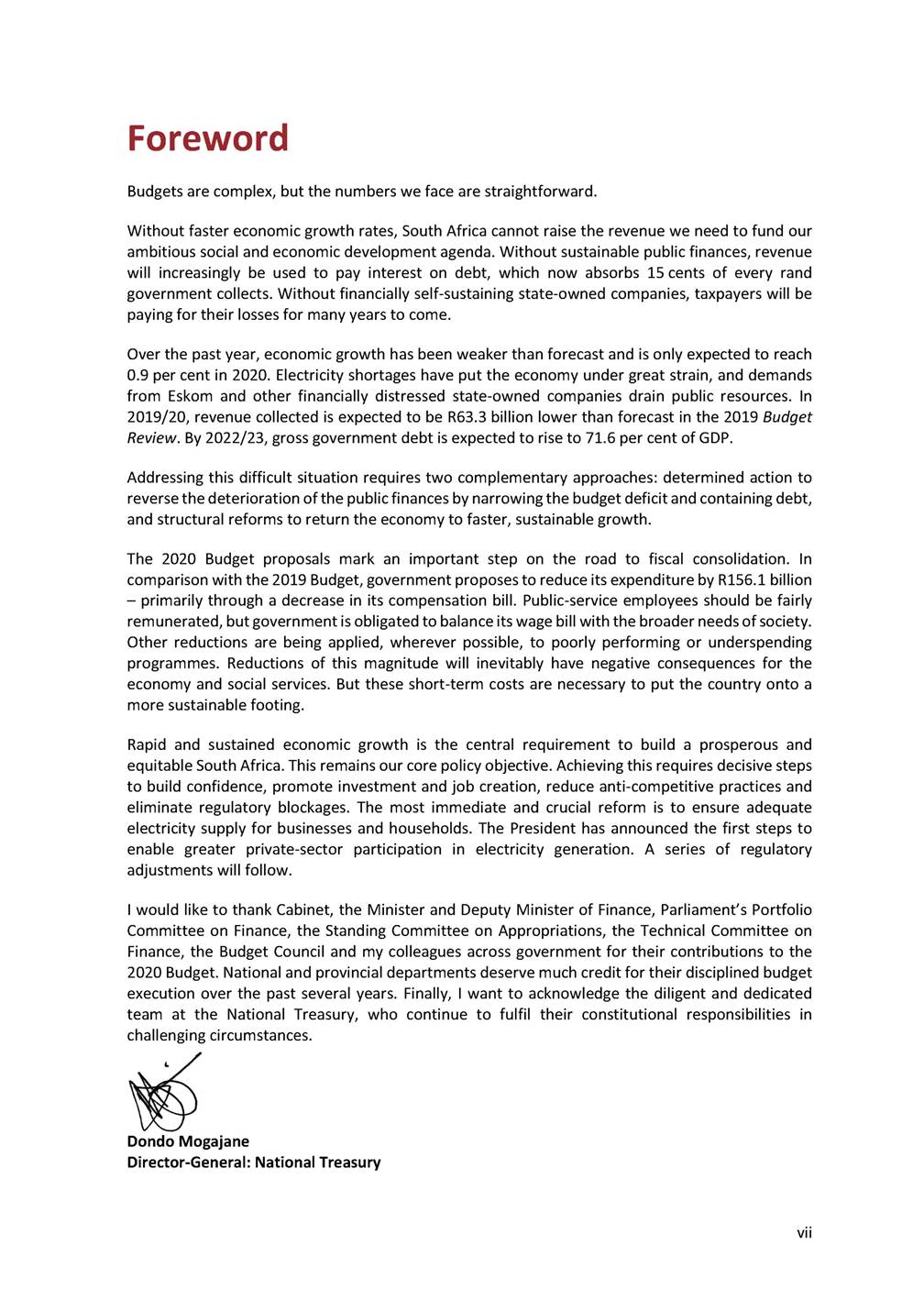

Foreword Budgets are complex, but the numbers we face are straightforward. Without faster economic growth rates, South Africa cannot raise the revenue we need to fund our ambitious social and economic development agenda. Without sustainable public finances, revenue will increasingly be used to pay interest on debt, which now absorbs 15 cents of every rand government collects. Without financially selfsustaining stateowned companies, taxpayers will be paying for their losses for many years to come. Over the past year, economic growth has been weaker than forecast and is only expected to reach 0.9 per cent in 2020. Electricity shortages have put the economy under great strain, and demands from Eskom and other financially distressed stateowned companies drain public resources. In 2019/20, revenue collected is expected to be R63.3 billion lower than forecast in the 2019 Budget Review. By 2022/23, gross government debt is expected to rise to 71.6 per cent of GDP. Addressing this difficult situation requires two complementary approaches: determined action to reverse the deterioration of the public finances by narrowing the budget deficit and containing debt, and structural reforms to return the economy to faster, sustainable growth. The 2020 Budget proposals mark an important step on the road to fiscal consolidation. In comparison with the 2019 Budget, government proposes to reduce its expenditure by R156.1 billion – primarily through a decrease in its compensation bill. Publicservice employees should be fairly remunerated, but government is obligated to balance its wage bill with the broader needs of society. Other reductions are being applied, wherever possible, to poorly performing or underspending programmes. Reductions of this magnitude will inevitably have negative consequences for the economy and social services. But these shortterm costs are necessary to put the country onto a more sustainable footing. Rapid and sustained economic growth is the central requirement to build a prosperous and equitable South Africa. This remains our core policy objective. Achieving this requires decisive steps to build confidence, promote investment and job creation, reduce anticompetitive practices and eliminate regulatory blockages. The most immediate and crucial reform is to ensure adequate electricity supply for businesses and households. The President has announced the first steps to enable greater privatesector participation in electricity generation. A series of regulatory adjustments will follow. I would like to thank Cabinet, the Minister and Deputy Minister of Finance, Parliament’s Portfolio Committee on Finance, the Standing Committee on Appropriations, the Technical Committee on Finance, the Budget Council and my colleagues across government for their contributions to the 2020 Budget. National and provincial departments deserve much credit for their disciplined budget execution over the past several years. Finally, I want to acknowledge the diligent and dedicated team at the National Treasury, who continue to fulfil their constitutional responsibilities in challenging circumstances. Dondo Mogajane DirectorGeneral: National Treasury vii

viii

Contents Overview…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Stabilising the public finances…………………………….…………………………………………………………………… Structural reforms for investment and growth….……………………………………………………………….……. Improving spending efficiency and reducing waste….……………………………………………………………… Summary of the budget…….…………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Budget documentation……………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Chapter 1 Consolidation, reform and growth………………………………………………………………………………………. 1 1 3 4 6 6 10 Chapter 2 Economic outlook……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Overview…..……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Reforms to boost confidence and investment..………….…………………………………………………………... Global outlook…..……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Domestic outlook……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Forecast trends…….……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….… Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 11 11 12 15 16 18 22 Chapter 3 Fiscal policy………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Overview………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…….. Changes in tax revenue and expenditure………….……………………………………….……….………………..… Achieving fiscal sustainability…………..…..………………………………………………………………………………… Fiscal framework……………………………..……………………………………………………………………………………… Elements of the consolidated budget……………………………………………………………………………………… Publicsector borrowing requirement…………………………………………………………………………………….. Risks to the fiscal outlook……………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 23 23 24 26 27 29 31 32 32 Chapter 4 Revenue trends and tax proposals….…………………………………………………………………………………… Overview………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Revenue collection and outlook…………..…………………………………………………………………………………. Tax policy………………………………..……….…………………………………………………………………………………….. Tax proposals……………………………………………….…………………………………………………………………………. Tax policy reviews and research………………………………………………………………………………………………. Measures to enhance tax administration…………………..…………………………………………………………… Conclusion…………………………………………….…………………..……………………………………………………………. 33 33 34 37 40 46 46 46 Chapter 5 Consolidated spending plans………………………………………………………………………………………………. Overview…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Revisions to main budget spending plans………………………………………………………………………………… Provisional allocations………………………..…………………………………………………………………………………… Consolidated government expenditure………………………………………………………………………………...... Spending priorities by function……………………………………………………………………………………………….. Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 47 47 48 50 51 52 63 Chapter 6 Division of revenue and spending by provinces and municipalities……………………………………… Overview…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Division of revenue…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Provincial revenue and spending…………………………………………………………………………………………….. Municipal revenue and spending…………………………………………………………………………………………….. Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 65 65 66 69 72 76 Chapter 7 Government debt and contingent liabilities………………………………………………………………………… Overview………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Financing strategy…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Borrowing performance and projections…….…………………………………………………………………………… Government debt and debtservice costs…….…………………………………………………………………………. Contingent liabilities……………………………..…….………………………………………………………………………….. Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 77 77 78 79 84 85 87 ix

Chapter 8 Financial position of publicsector institutions…………………………………………………………………….. Overview…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Stateowned companies ………………..………………………………………………………………………….……………. Development finance institutions………………………….…………………………………………………..…………… Social security funds…………………………………………………..…………………………………………………………… Government Employees Pension Fund……………………………………………………………………………………. 89 89 90 95 96 98 Annexure A Annexure B Annexure C Annexure D Annexure E Annexure F Report of the Minister of Finance to Parliament………………………………………………………………….. Tax expenditure statement…………….…………………………………………………………………………………… Additional tax policy and administrative adjustments…………………………………………………………. Publicsector infrastructure update…..………………………………………………………………………………… Financial sector update…....……………………………………………………………………………………………….. Summary of the budget …………………………………………………………..…….………………………………….. 101 119 125 143 153 157 161 177 Glossary………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Statistical annexure………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Two annexures are available on the National Treasury website (www.treasury.gov.za): W1 W2 Explanatory memorandum to the division of revenue Structure of the government accounts x

Tables 7.9 7.10 Government guarantee exposure ..................................... 86 Provision for multilateral institutions and other contingent liabilities.......................................................... 87 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Macroeconomic outlook – summary ............................ Consolidated government fiscal framework ................. Impact of tax proposals on 2020/21 revenue ............... Consolidated government expenditure by function ..... Division of revenue ....................................................... 7 7 8 8 9 8.1 Combined balance sheets of state owned companies……………………………………………………………….. ..... 90 Summary of recapitalisation and bailouts of state owned companies………………………………………………… 91 Borrowing requirement of selected state owned companies ........................................................................ 93 Financial position of selected development finance institutions…………………………………………………… ..... 95 Borrowing requirement for development finance institutions ....................................................................... 96 Financial position of social security funds ........................ 97 Selected income and expenditure of GEPF ....................... 98 Breakdown of assets under management by PIC ............. 98 8.2 Projected state debt and debt service costs ................. 10 Combined financial position of public institutions ........ 10 8.3 2.1 2.2 2.3 Economic growth in selected countries ........................ 15 Macroeconomic performance and projections ............. 16 Sector performance ...................................................... 22 8.4 8.5 3.1 3.2 3.3 Macroeconomic performance and projections ............. 23 Revised gross tax revenue projections .......................... 24 Adjustments to main budget non interest expenditure since 2019 Budget .................................... 25 Consolidated fiscal framework...................................... 26 Main budget expenditure ceiling, budgeted estimates and outcomes ............................................... 27 Consolidated operating and capital accounts ............... 28 Main budget framework ............................................... 30 Revisions to main budget revenue and expenditure estimates ……………………………………… ............................. 31 Consolidated budget balances ...................................... 31 Public sector borrowing requirement ........................... 32 8.6 8.7 8.8 3.4 3.5 Figures 1.1 1.2 Gross debt to GDP outlook .............................................. 2 Debt service costs as proportion of main budget revenue ............................................................................ 2 Compensation of employees as share of consolidated expenditure................................................. 2 Financial support provided for state owned companies ........................................................................ 2 3.6 3.7 3.8 1.3 3.9 3.10 1.4 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Budget estimates and revenue outcomes..................... 35 Budget revenue............................................................. 36 Impact of tax proposals on 2020/21 revenue ............... 40 Personal income tax rates and bracket adjustments.................................................................. 41 Estimates of individual taxpayers and taxable income ......................................................................... 41 Transfer duty rate adjustments..................................... 43 Changes in specific excise duties................................... 44 Total combined fuel taxes on petrol and diesel ............ 44 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 2.10 Government spending composition ................................. 12 Confidence and private investment.................................. 12 Rising debt in developing countries.................................. 16 Emerging market currencies ............................................ 16 GDP growth scenarios ...................................................... 18 Growth by expenditure, 2019........................................... 18 Growth by sector, 2019 .................................................... 18 Investment contribution................................................... 20 Core inflationary pressures .............................................. 21 Administered price inflation ............................................. 21 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 5.1 Adjustments to main budget non interest expenditure since 2019 Budget ....................................................... 48 Reallocations to baselines over the MTEF period ......... 49 Largest baseline reductions over the MTEF period............................................................................ 50 Provisional allocations not assigned to votes................ 51 Consolidated government expenditure by economic classification.................................................................. 51 Consolidated government expenditure by function ..... 53 Learning and culture expenditure ................................. 55 Social protection expenditure ....................................... 56 Average monthly social grant values............................. 57 Health expenditure ....................................................... 58 Community development expenditure ......................... 59 Economic development expenditure ............................ 60 Peace and security expenditure .................................... 62 General public services expenditure ............................. 63 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Main budget revenue and expenditure ............................ 24 Budget deficit ................................................................... 24 Composition of consolidated government spending ........ 26 Average nominal growth in consolidated spending.......... 29 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 4.1 Tax burdens for countries at different levels of development .................................................................... 38 Corporate income tax rate movements............................ 39 4.2 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.1 5.2 Average nominal growth in spending………………………....... 52 Consolidated government expenditure by function ......... 52 6.1 6.2 6.3 Transfers increase in line with population growth ........... 67 Municipal operating revenue……… ................................... 74 Funded and unfunded municipal budgets ........................ .75 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Sensitivity of debt and debt service costs ........................ 79 Debt maturity profile........................................................ 80 Ownership of domestic bonds .......................................... 82 Domestic bonds held by foreign investors........................ 82 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Division of nationally raised revenue………………….………. 66 Provincial equitable share………………………………………….. 70 Conditional grants to provinces .................................... 72 Transfers to local government ...................................... 73 8.1 8.2 Negative cash flows at state owned companies............... 91 Debt maturity profile of major state owned companies ........................................................................ 92 Borrowing costs of state owned companies and development finance institutions, 2018/19 ..................... .92 RAF liabilities .................................................................... 97 RAF annual deficit............................................................. 97 7.1 Performance against strategic portfolio risk benchmarks ................................................................... 78 Financing of national government gross borrowing requirement................................................................... 81 Domestic short term borrowing .................................... 81 Foreign currency commitments and financing .............. 83 Change in cash balances ................................................ 83 Total national government debt .................................... 84 Analysis of annual increase in gross loan debt............... 84 National government debt service costs ....................... 85 8.3 7.2 8.4 8.5 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 xi

xii

1 Consolidation, reform and growth Overview Iof the economy, spending plans based on an assumption of economic n 2019, consolidated government spending reached a historic high of Government spending has reached a historic high of 36 per cent of GDP 36 per cent of GDP. This increase reflects downward revisions to the size growth that has not materialised, and increased demands from financially distressed state-owned companies. While government makes a significant contribution to development, this level of spending is unsustainable, and results in continued high deficits and debt accumulation. A year ago, the Budget Review projected real economic growth of 1.5 per cent in 2019 and 1.7 per cent in 2020. We now expect real growth of only 0.3 per cent in 2019 and 0.9 per cent in 2020. The impact of low growth on revenue collection has been considerable. Government expects to collect R63.3 billion less revenue than projected at the time of the 2019 Budget. The state is borrowing at an increased rate to The state is borrowing at an increased rate – not to build infrastructure, but to fund operations 1 In brief •The 2020 Budget proposes total consolidated spending of R1.95 trillion in 2020/21, with the largest allocations going to learning and culture (R396.4 billion), health (R229.7 billion) and social development (R309.5 billion). •The economic outlook is weak. Real GDP is expected to grow at 0.9 per cent in 2020, 1.3 per cent in 2021 and 1.6 per cent in 2022. Achieving faster economic growth requires far-reaching structural reforms. •The public finances continue to deteriorate. Low growth has led to a R63.3 billion downward revision to estimates of tax revenue in 2019/20 relative to the 2019 Budget. Debt is not projected to stabilise over the medium term, and debt-service costs now absorb 15.2 per cent of main budget revenue. •Halting the fiscal deterioration requires a combination of continued spending restraint, faster economic growth, and measures to contain financial demands from distressed state-owned companies. •As a first step, the 2020 Budget makes net non-interest spending reductions of R156.1 billion in total over the next three years compared with last year’s budget projections. This includes large reductions to the public-service wage bill.

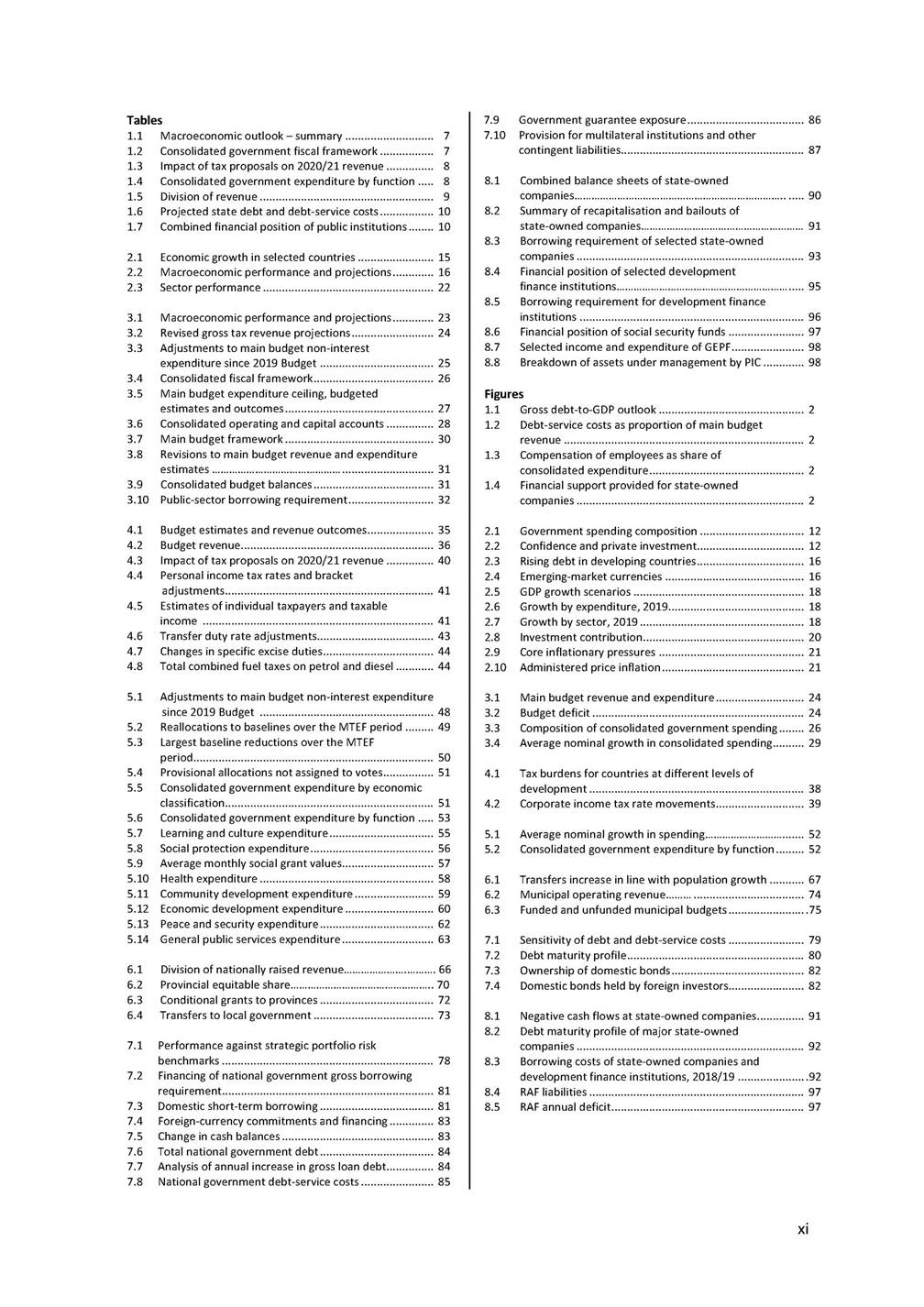

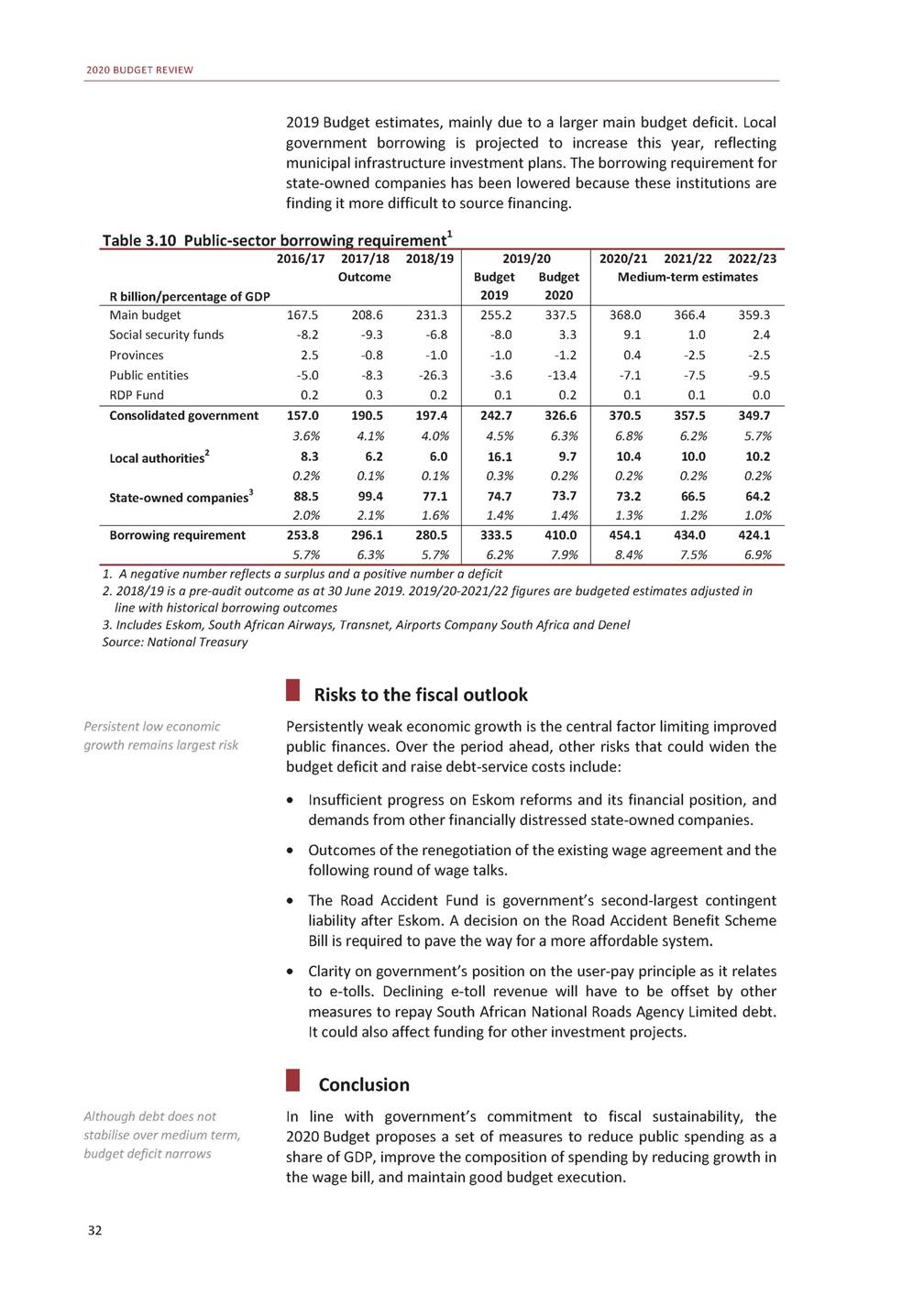

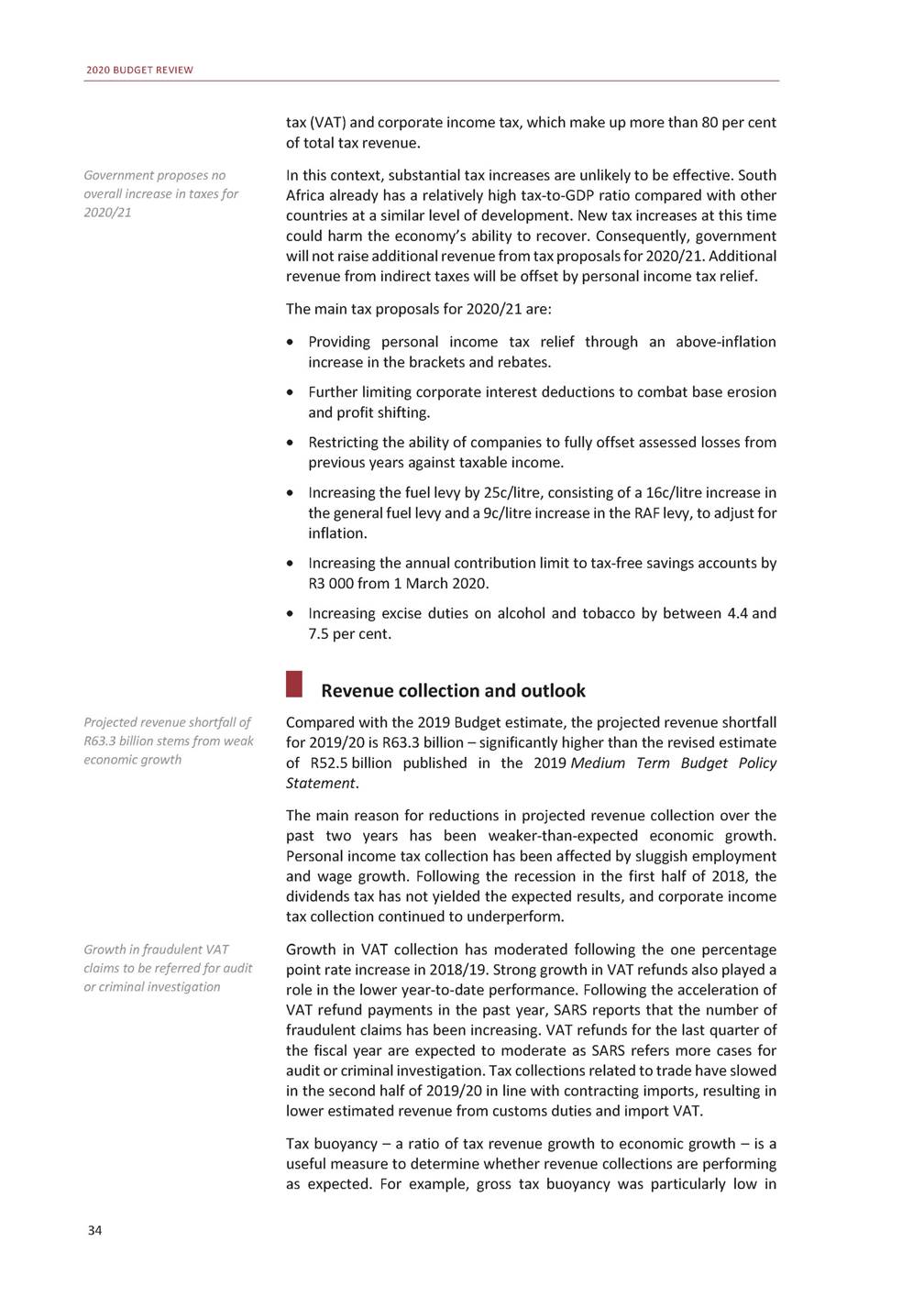

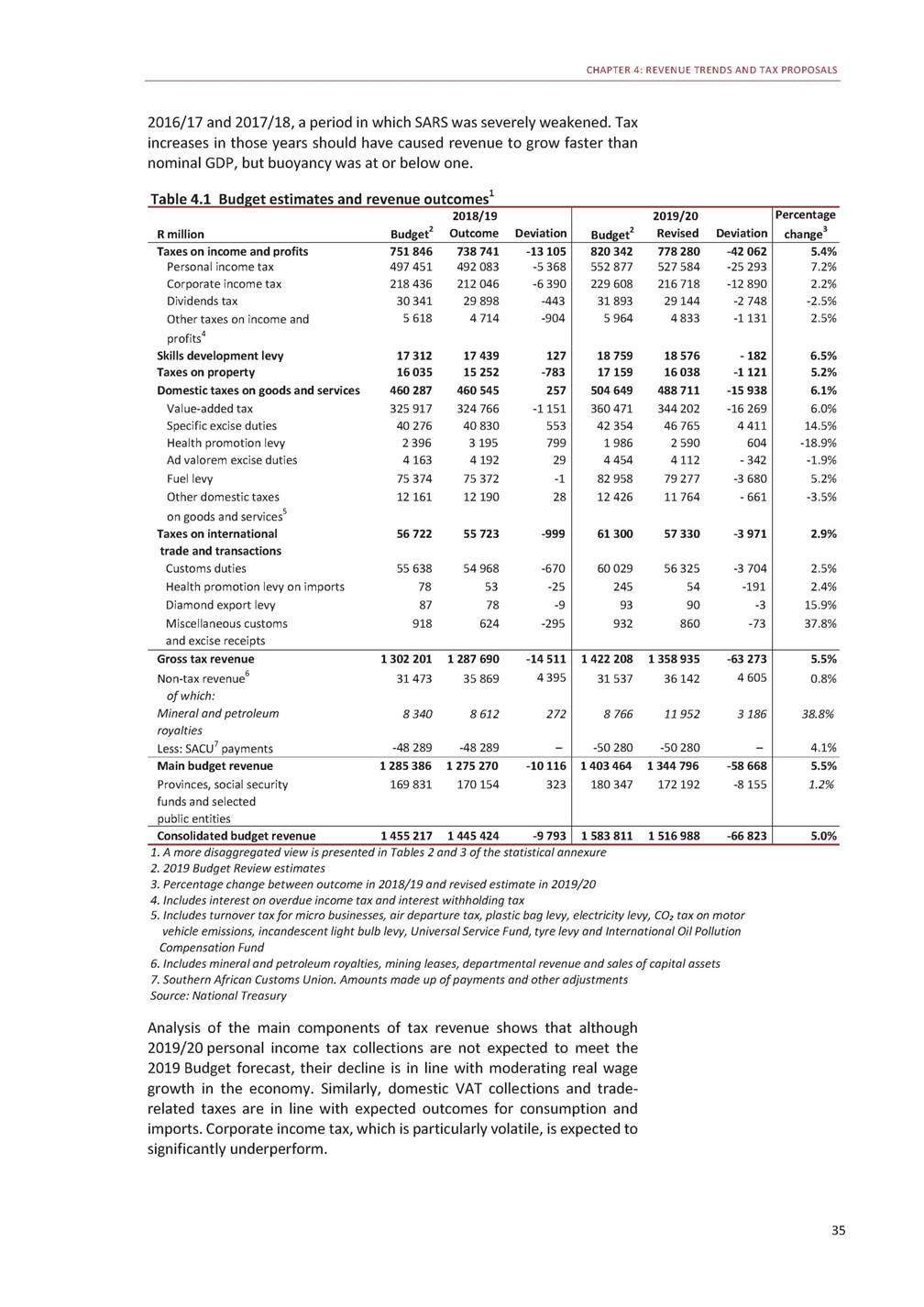

2020 BUDGET REVIEW fund operations, with the deficit projected at 6.3 per cent of GDP this year. Debt-service costs now absorb 15 cents of every rand government collects. By 2022/23, interest payments will exceed health spending. As a major step towards fiscal sustainability, government has reduced the main budget expenditure baseline by R156.1 billion over the next three years in comparison with 2019 Budget projections. This is approximately 1 per cent of GDP per year. The net reduction is mainly the result of the following changes over the medium term: • Reductions to baselines of R261 billion, which includes a R160.2 billion reduction to the wage bill of national and provincial departments, and national public entities. • Reallocations and additions totalling R111.1 billion, of which R60.1 billion is set aside for Eskom and South African Airways (SAA). Non-interest expenditure is forecast to grow at 3.8 per cent over the next three years, down from an average of 8.4 per cent over the past three years. Despite slower growth in spending, the deficit is forecast to remain in excess of 6 per cent of GDP next year, as a result of lower economic growth and tax revenue projections. The scale of the challenge requires fundamental changes to support economic growth, continued restraint in spending growth and improved spending efficiency. Baseline expenditure reductions of R261 billion partially offset by R60 billion set aside for Eskom and SAA 2019 Budget 2020 Budget 20 69. 14 12 61.6 59.7 56.7 58.9 56.2 53.0 55.6 6 4 48.9 36.5 36 35.6 60 35.5 2 Per cent Per cent of GDP 2005/06 2006/07 2007/08 2008/09 2009/10 2010/11 2011/12 2012/13 2013/14 2014/15 2015/16 2016/17 2017/18 2018/19 2015/16 2016/17 2017/18 2018/19 2019/20 2020/21 2021/22 2022/23 R billion Per cent 2008/09 2009/10 2010/11 2011/12 2012/13 2013/14 2014/15 2015/16 2016/17 2017/18 2018/19 2019/20 2020/21 2021/22 2022/23 2010/11 2011/12 2012/13 2013/14 2014/15 2015/16 2016/17 2017/18 2018/19 2019/20 2020/21 2021/22 2022/23 Figure 1.1 Gross debt-to-GDP outlookFigure 1.2 Debt-service costs as proportion of main budget revenue 72 71.6 18 16 65.6 64 10 56 57.8 8 50.5 48 2 0 Figure 1.3 Compensation of employees as share ofFigure 1.4 Financial support provided for consolidated expenditurestate-owned companies 37 80 South African Broadcasting Corporation 70 South African Express 35.7 35 35.2 50 34.6 40 34 30 33 32.9 33.2 20 32.6 32.7 10 32 0 Source: National Treasury Denel South African Airways Eskom 1

CHAPTER 1: CONSOLIDATION, REFORM AND GROWTH To achieve faster economic growth, South Africa requires structural reforms in a number of areas. Most urgently, the regulatory path should be cleared to enable the private sector to generate electricity, contributing both financial and technical capacity to the country’s energy needs. In other areas, cumbersome and unpredictable regulatory frameworks are undermining private investment. The President’s State of the Nation Address made several announcements in this regard, and more decisive steps will be required in the months ahead. Most urgent structural reform is to clear path for private-sector electricity generation Stabilising the public finances Achieving fiscal sustainability requires a combination of continued spending restraint, faster economic growth and measures to contain extra-budgetary pressures – including reform of state-owned companies. Since 2012/13, government has taken steps to reduce spending growth and raise tax revenue. As a result of lower nominal GDP and revenue growth, however, these interventions have not stabilised debt. Revenue and expenditure are near or at historic highs as a share of GDP. Over the same period, the composition of spending has deteriorated. Debt-service costs have been the fastest-growing area of spending, rising from 9.8 per cent of main budget revenue in 2010/11 to 15.2 per cent in 2019/20. The wage bill has grown strongly over this period, averaging 35.4 per cent of total consolidated expenditure. Over the past five years, the majority of efforts to reduce the deficit have come through tax increases. The 2020 Budget centres the consolidation effort on expenditure, by reducing compensation growth. The aim is to reduce spending as a share of GDP, and improve the composition of spending. Government will not raise additional revenue from tax proposals for 2020/21. Debt-service costs have been fastest-growing category of expenditure Towards a sustainable wage bill Government recognises that public-service employees should be fairly remunerated, but is obligated to balance compensation demands with the broader needs of society as reflected in the budget. Civil servants’ salaries have grown by about 40 per cent in real terms over the past 12 years, without equivalent increases in productivity. Growth in the wage bill has begun crowding out spending on capital projects for future growth and items that are critical for service delivery. The 2020 Budget Review includes R160.2 billion in medium-term reductions to the wage bill. This will affect national and provincial departments, and national public entities that receive transfers from government. Government has tabled an agenda item on the management of the public-service wage bill at the Public Service Co-ordinating Bargaining Council, and will discuss with unions options for achieving the required reduction. This target can be achieved through a combination of modifications to cost-of-living adjustments, pay progression and other benefits. The proposed wage reductions will see consolidated compensation spending contract by 1 per cent in real terms over the medium term. Goods and services and capital budgets will continue to grow in real terms. Government is obligated to balance fair compensation with needs of broader society 3

2020 BUDGET REVIEW Revenue considerations In preparing the 2020 Budget, government considered but decided against proposing tax increases. The main factors in this decision were the weakness of the economy and, in the context of the muted growth outlook, the elevated tax-to-GDP ratio of 26.3 per cent. Government’s short-term focus is to rebuild the capacity of the South African Revenue Service (SARS) and public trust in the institution. No overall tax increase proposed for 2020/21 State-owned companies Over the past 12 years, government has allocated R162 billion to financially distressed state-owned companies, of which Eskom accounts for 82 per cent. Fiscal support for Eskom, as outlined in Annexure C of the 2019 Medium Term Budget Policy Statement (MTBPS), remains unchanged. The roadmap on Eskom, published by the Minister of Public Enterprises, outlines the reform process. Eskom has begun the process of separating its three operating activities – generation, transmission and distribution – each of which will soon have its own board and management structure. These are the first steps in the necessary restructuring of South Africa’s electricity sector for the 21st century. SAA’s board placed the airline into voluntary business rescue in December 2019 as a result of its inability to meet financial obligations. Since 2008/09, SAA has incurred net losses of over R32 billion. Government has set aside R16.4 billion for SAA over the medium term to repay the airline’s guaranteed debt and to cover debt-service costs. The costs of this adjustment are still being finalised, and will be financed from existing provisional allocations for state-owned companies. R16.4 billion set aside for SAA to repay guaranteed debt and cover debt-service costs Structural reforms for investment and growth South Africa needs much faster economic growth to promote investment, create jobs, and enable the state to sustainably grow the revenue that pays for social and developmental programmes. These objectives underpin Economic Transformation, Inclusive Growth, and Competitiveness: Towards an Economic Strategy for South Africa – a discussion document released by the National Treasury in August 2019. The barriers to economic growth are complex and require structural reforms. In other words, the cost of doing business, the cost of finding or conducting work, and the cost of living must be meaningfully reduced. Such reforms will help to transform the economy by improving the profitability of existing businesses, encouraging the start-up of new enterprises, boosting private-sector investment, creating jobs and reducing unemployment, and improving the purchasing power of all households. South Africa’s macroeconomic policy provides a sound platform for the success of structural reforms. Government is committed to low and stable inflation, a flexible exchange rate and a sustainable fiscal framework. These policy commitments in turn reduce uncertainty and risk in investment decisions, and support business and consumer confidence. The Constitution entrenches the rule of law, and commits South Africa to transparent public finances, accompanied by expenditure controls, and a central bank that executes its functions independently. Reforms needed to promote investment, create jobs and enable state to sustainably grow revenue Low and stable inflation, flexible exchange rate, rule of law and transparent public finances promote certainty 4

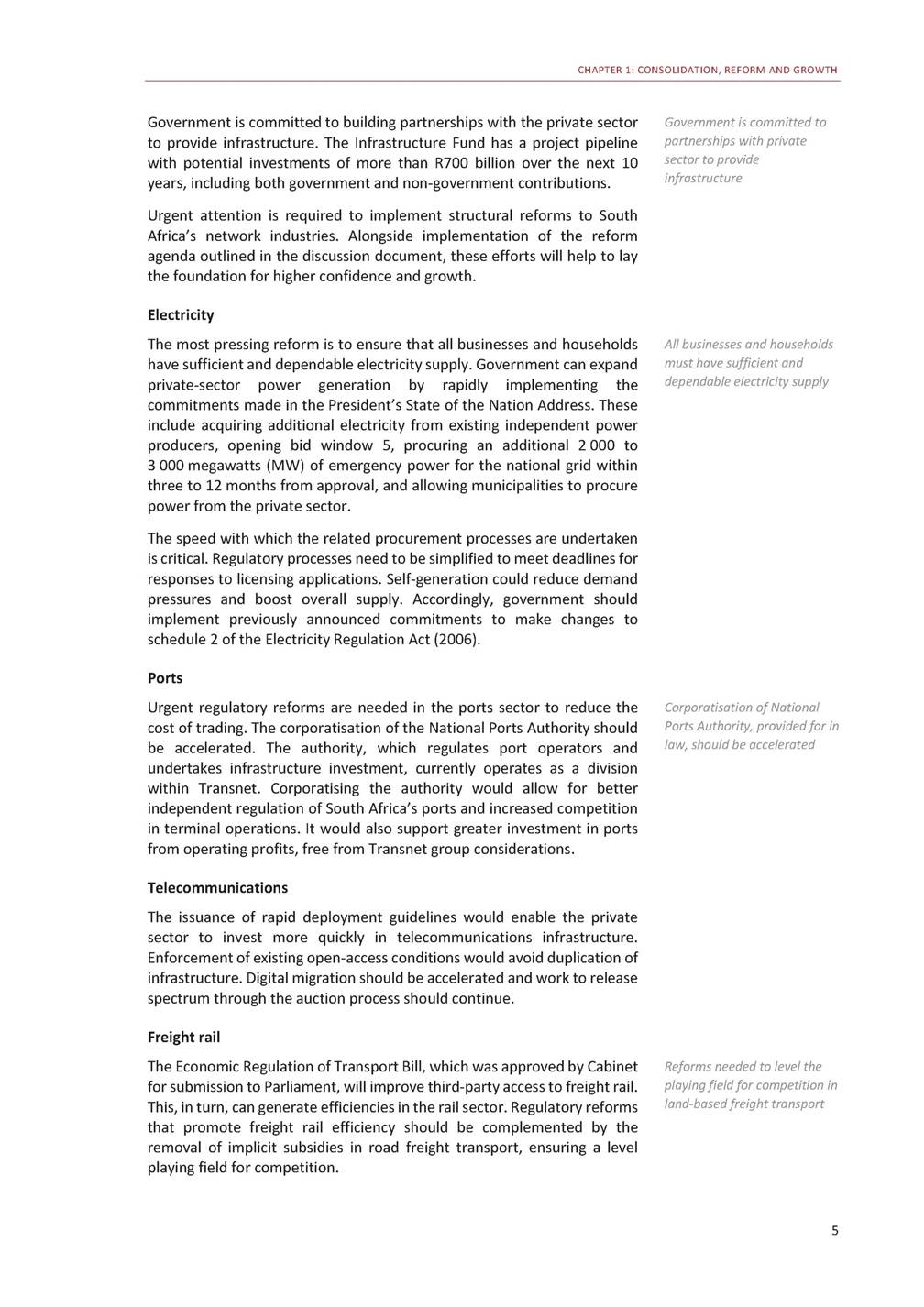

CHAPTER 1: CONSOLIDATION, REFORM AND GROWTH Government is committed to building partnerships with the private sector to provide infrastructure. The Infrastructure Fund has a project pipeline with potential investments of more than R700 billion over the next 10 years, including both government and non-government contributions. Urgent attention is required to implement structural reforms to South Africa’s network industries. Alongside implementation of the reform agenda outlined in the discussion document, these efforts will help to lay the foundation for higher confidence and growth. Government is committed to partnerships with private sector to provide infrastructure Electricity The most pressing reform is to ensure that all businesses and households have sufficient and dependable electricity supply. Government can expand private-sector power generation by rapidly implementing the commitments made in the President’s State of the Nation Address. These include acquiring additional electricity from existing independent power producers, opening bid window 5, procuring an additional 2 000 to 3 000 megawatts (MW) of emergency power for the national grid within three to 12 months from approval, and allowing municipalities to procure power from the private sector. The speed with which the related procurement processes are undertaken is critical. Regulatory processes need to be simplified to meet deadlines for responses to licensing applications. Self-generation could reduce demand pressures and boost overall supply. Accordingly, government should implement previously announced commitments to make changes to schedule 2 of the Electricity Regulation Act (2006). All businesses and households must have sufficient and dependable electricity supply Ports Urgent regulatory reforms are needed in the ports sector to reduce the cost of trading. The corporatisation of the National Ports Authority should be accelerated. The authority, which regulates port operators and undertakes infrastructure investment, currently operates as a division within Transnet. Corporatising the authority would allow for better independent regulation of South Africa’s ports and increased competition in terminal operations. It would also support greater investment in ports from operating profits, free from Transnet group considerations. Corporatisation of National Ports Authority, provided for in law, should be accelerated Telecommunications The issuance of rapid deployment guidelines would enable the private sector to invest more quickly in telecommunications infrastructure. Enforcement of existing open-access conditions would avoid duplication of infrastructure. Digital migration should be accelerated and work to release spectrum through the auction process should continue. Freight rail The Economic Regulation of Transport Bill, which was approved by Cabinet for submission to Parliament, will improve third-party access to freight rail. This, in turn, can generate efficiencies in the rail sector. Regulatory reforms that promote freight rail efficiency should be complemented by the removal of implicit subsidies in road freight transport, ensuring a level playing field for competition. Reforms needed to level the playing field for competition in land-based freight transport 5

2020 BUDGET REVIEW Improving spending efficiency and reducing waste Government’s contribution to the economy is not matched by adequate spending efficiency. Reports by the Auditor-General have consistently highlighted patterns of wasteful expenditure. Reforms under way include: Reforms under way to improve procurement, strengthen provincial grants, reduce claims against the state • Procurement – The state maintains a complex and often ineffective procurement system. Some measures have had the unintended effect of severely hampering government’s ability to efficiently contract for goods and services. Many of these regulations can be reformed to make legitimate procurement easier without undermining the necessary anti-corruption safeguards. As a first step, the draft Public Procurement Bill has been gazetted for public comment. • Provincial unfunded municipal grants – Government has made progress in reducing municipal budgets and is piloting initiatives to improve revenue collection. Following a review, government is introducing several changes to the provincial grant system. Medico-legal claims – Medical malpractice claims and litigation against the state have increased rapidly in recent years. Although in many cases the quality of care is insufficient, the increase in claims is inconsistent with certain indicators of health outcomes in the public sector. Work has begun to limit unreasonable claims against the state. Public office bearers – There will be no increase in the salaries of public office bearers in 2020/21. This follows a reduction in benefits stemming from changes to the Ministerial Handbook. • • Over the period ahead, the following interventions will be undertaken: Tax incentives to be reviewed and expenditure to be assessed to improve efficiency • South Africa’s tax incentive system favours incumbents and those able to afford specialist tax advice. Over the medium term, government will conduct a review of such incentives, repealing or redesigning those that are redundant, inefficient or inequitable. The National Treasury and the Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation will undertake a new round of expenditure reviews to identify cost savings and improve efficiency. Government will publish a new law this year introducing a remuneration framework for public entities and state-owned companies. One goal of this legislation is to eliminate excessive salaries and bonuses being awarded to executives and managers. • • Over the next year, the National Treasury and the Department of Public Service and Administration will improve the wage-setting mechanism; report on the causes of unauthorised and wasteful expenditure; and examine ways to reduce state litigation, accommodation and information technology costs. Summary of the budget Economic outlook The economic growth outlook has weakened since the 2019 MTBPS, following lower-than-expected growth in the second half of the year. 6

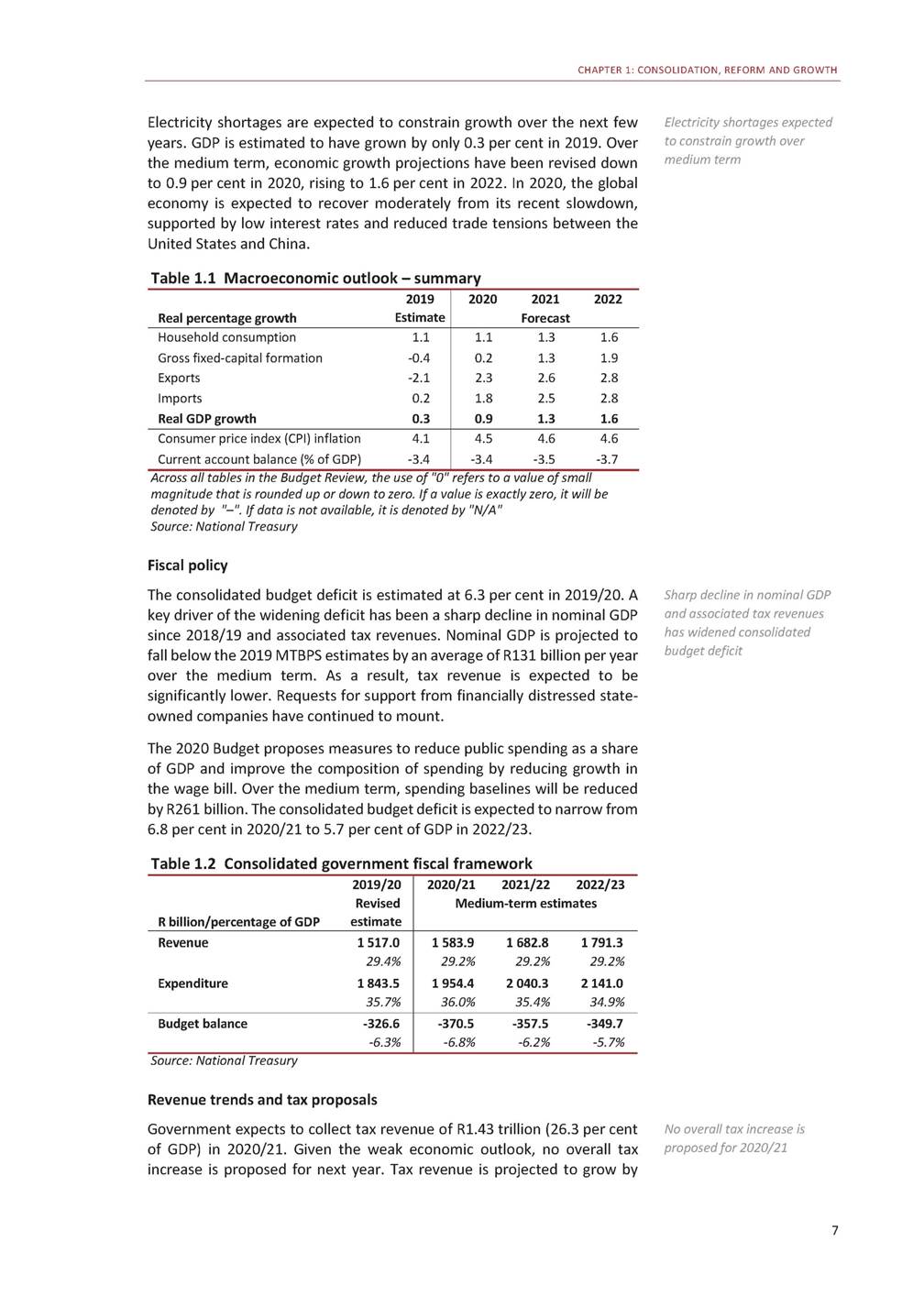

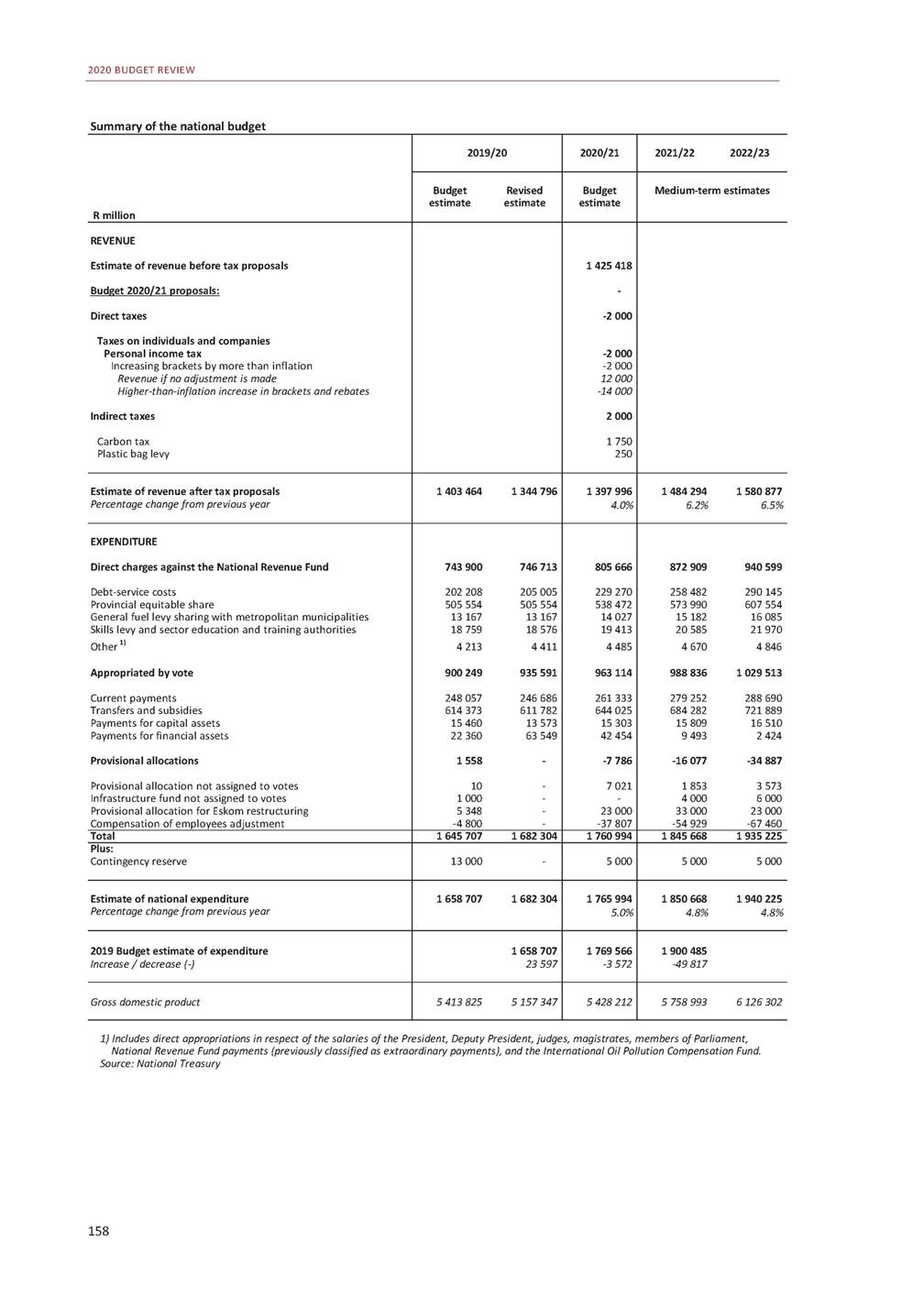

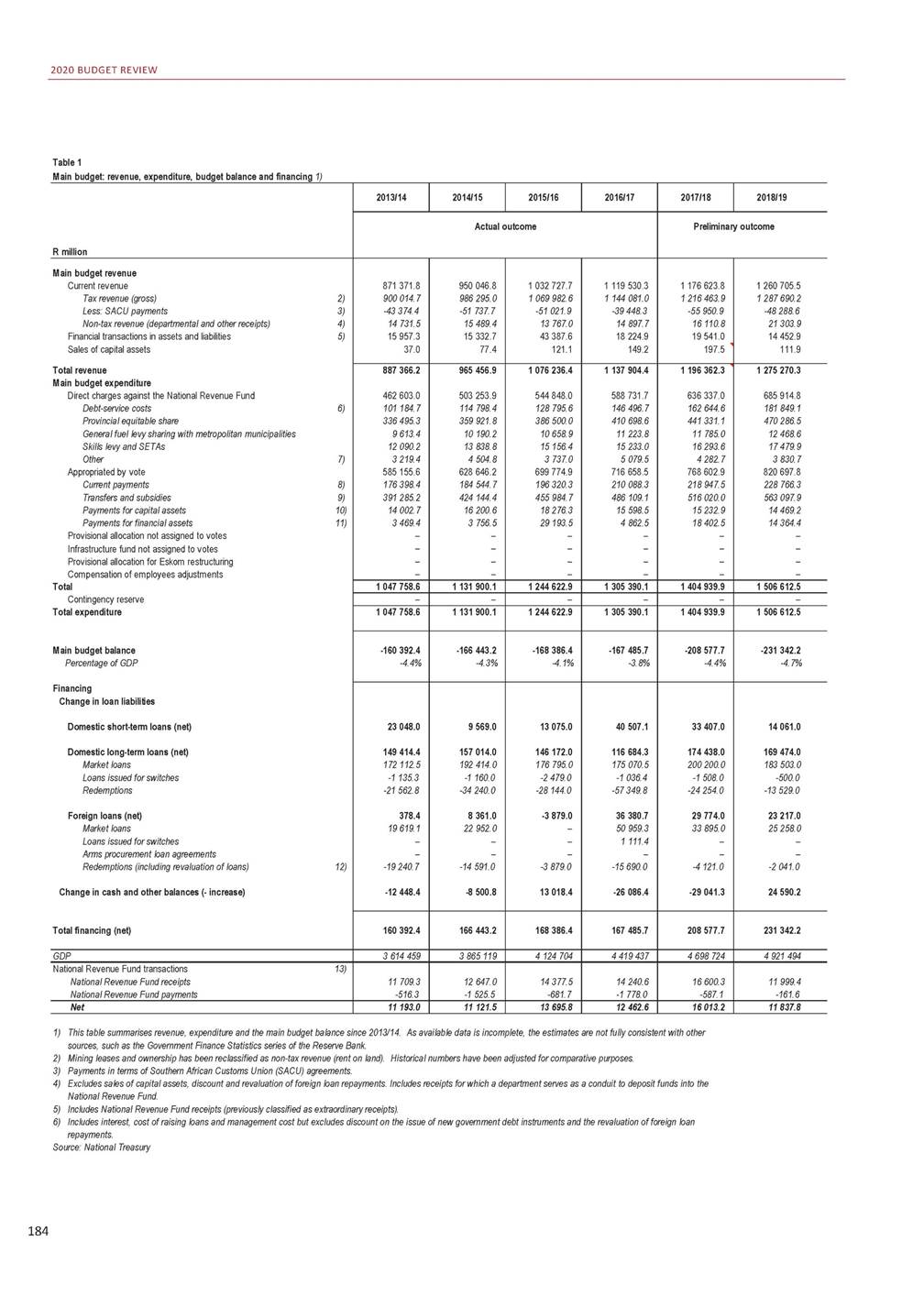

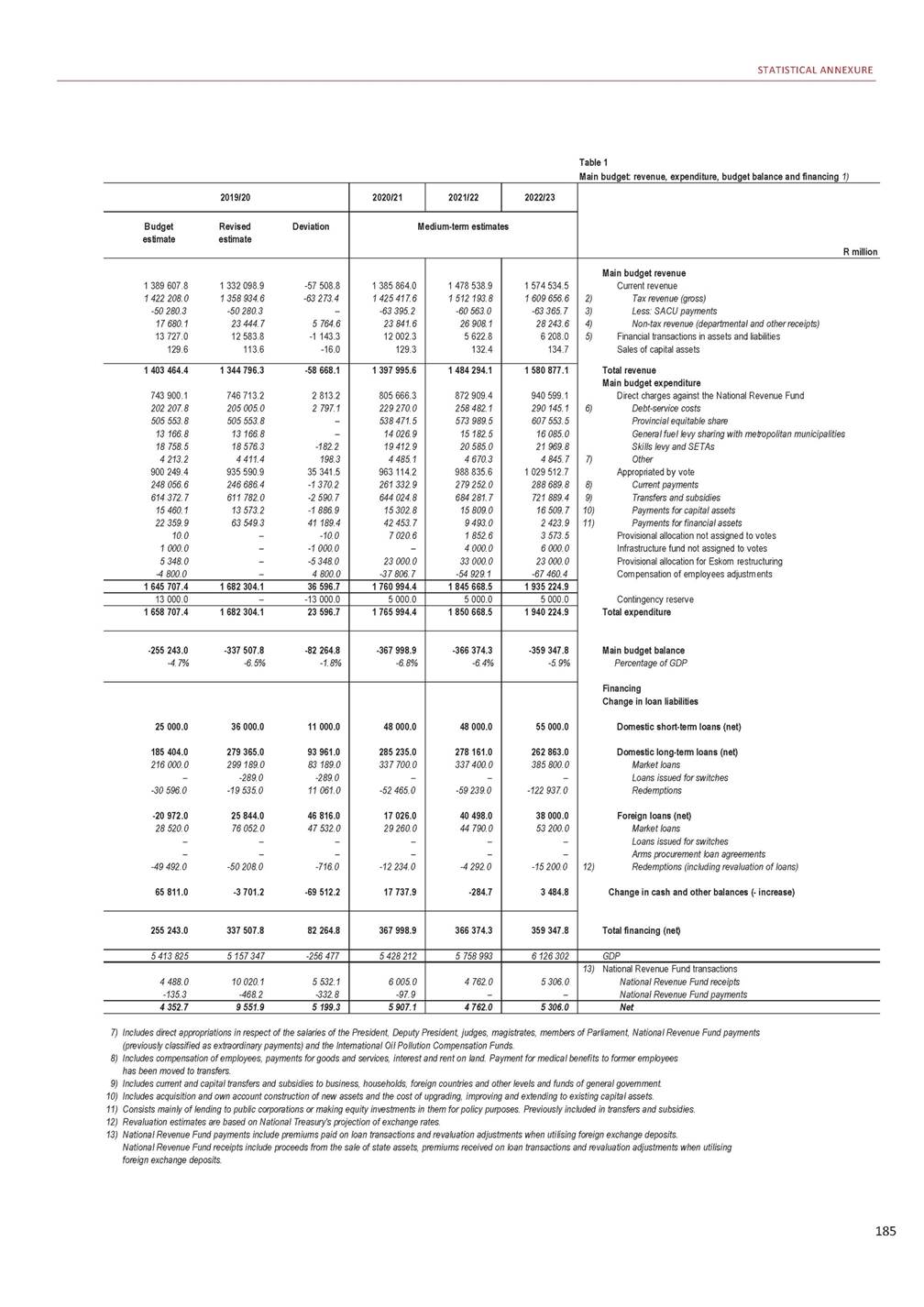

CHAPTER 1: CONSOLIDATION, REFORM AND GROWTH Electricity shortages are expected to constrain growth over the next few years. GDP is estimated to have grown by only 0.3 per cent in 2019. Over the medium term, economic growth projections have been revised down to 0.9 per cent in 2020, rising to 1.6 per cent in 2022. In 2020, the global economy is expected to recover moderately from its recent slowdown, supported by low interest rates and reduced trade tensions between the United States and China. Electricity shortages expected to constrain growth over medium term Table 1.1 Macroeconomic outlook – summary Across all tables in the Budget Review, the use of "0" refers to a value of small magnitude that is rounded up or down to zero. If a value is exactly zero, it will be denoted by "–". If data is not available, it is denoted by "N/A" Source: National Treasury Fiscal policy The consolidated budget deficit is estimated at 6.3 per cent in 2019/20. A key driver of the widening deficit has been a sharp decline in nominal GDP since 2018/19 and associated tax revenues. Nominal GDP is projected to fall below the 2019 MTBPS estimates by an average of R131 billion per year over the medium term. As a result, tax revenue is expected to be significantly lower. Requests for support from financially distressed state-owned companies have continued to mount. The 2020 Budget proposes measures to reduce public spending as a share of GDP and improve the composition of spending by reducing growth in the wage bill. Over the medium term, spending baselines will be reduced by R261 billion. The consolidated budget deficit is expected to narrow from 6.8 per cent in 2020/21 to 5.7 per cent of GDP in 2022/23. Table 1.2 Consolidated government fiscal framework Sharp decline in nominal GDP and associated tax revenues has widened consolidated budget deficit Source: National Treasury Revenue trends and tax proposals Government expects to collect tax revenue of R1.43 trillion (26.3 per cent of GDP) in 2020/21. Given the weak economic outlook, no overall tax increase is proposed for next year. Tax revenue is projected to grow by No overall tax increase is proposed for 2020/21 7 2019/20 Revised R billion/percentage of GDPestimate 2020/212021/222022/23 Medium-term estimates Revenue1 517.0 29.4% Expenditure1 843.5 35.7% 1 583.91 682.81 791.3 29.2%29.2%29.2% 1 954.42 040.32 141.0 36.0%35.4%34.9% Budget balance-326.6 -6.3% -370.5-357.5-349.7 -6.8%-6.2%-5.7% 2019 Real percentage growthEstimate 202020212022 Forecast Household consumption1.1 Gross fixed-capital formation-0.4 Exports-2.1 Imports0.2 Real GDP growth0.3 1.11.31.6 0.21.31.9 2.32.62.8 1.82.52.8 0.91.31.6 Consumer price index (CPI) inflation4.1 Current account balance (% of GDP)-3.4 4.54.64.6 -3.4-3.5-3.7

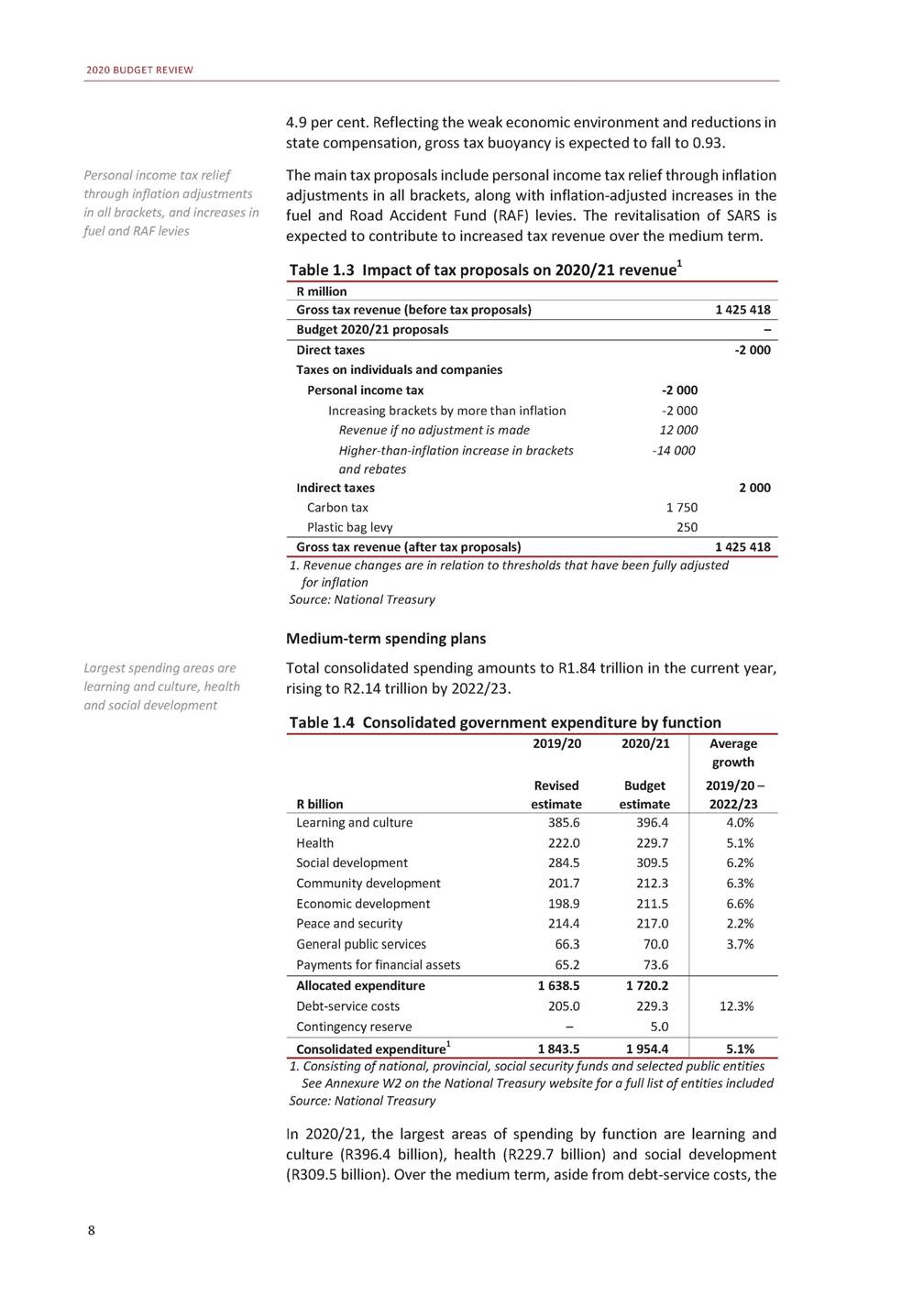

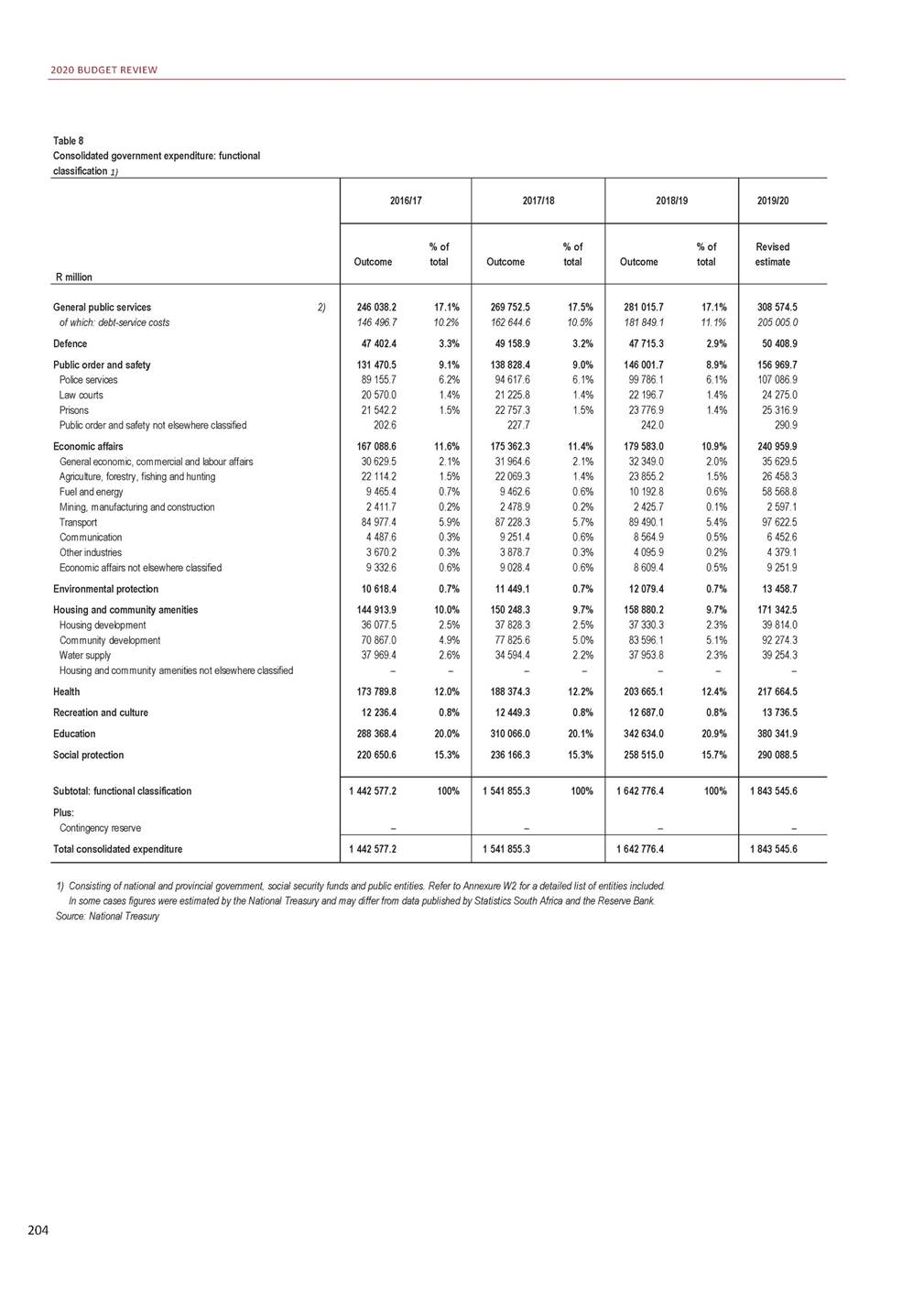

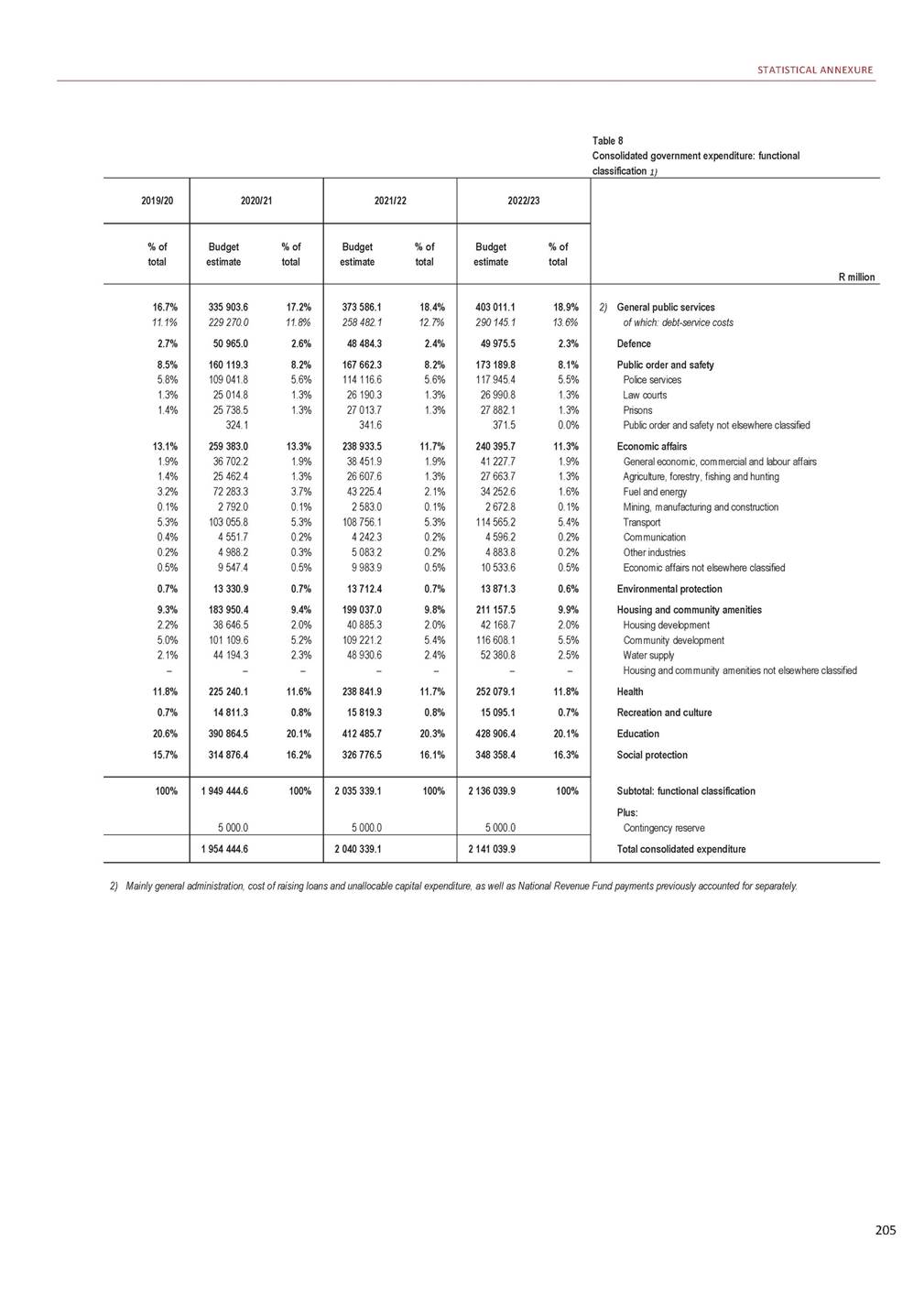

2020 BUDGET REVIEW 4.9 per cent. Reflecting the weak economic environment and reductions in state compensation, gross tax buoyancy is expected to fall to 0.93. The main tax proposals include personal income tax relief through inflation adjustments in all brackets, along with inflation-adjusted increases in the fuel and Road Accident Fund (RAF) levies. The revitalisation of SARS is expected to contribute to increased tax revenue over the medium term. Table 1.3 Impact of tax proposals on 2020/21 revenue1 Personal income tax relief through inflation adjustments in all brackets, and increases in fuel and RAF levies R million Gross tax revenue (before tax proposals) 1 425 418 Budget 2020/21 proposals – Direct taxes Taxes on individuals and companies Personal income tax Increasing brackets by more than inflation Revenue if no adjustment is made Higher-than-inflation increase in brackets and rebates Indirect taxes Carbon tax Plastic bag levy -2 000 -2 000 -2 000 12 000 -14 000 2 000 1 750 250 Gross tax revenue (after tax proposals) 1 425 418 1. Revenue changes are in relation to thresholds that have been fully adjusted for inflation Source: National Treasury Medium-term spending plans Total consolidated spending amounts to R1.84 trillion in the current year, rising to R2.14 trillion by 2022/23. Largest spending areas are learning and culture, health and social development Table 1.4 Consolidated government expenditure by function 1. Consisting of national, provincial, social security funds and selected public entities See Annexure W2 on the National Treasury website for a full list of entities included Source: National Treasury In 2020/21, the largest areas of spending by function are learning and culture (R396.4 billion), health (R229.7 billion) and social development (R309.5 billion). Over the medium term, aside from debt-service costs, the 8 2019/202020/21 RevisedBudget R billionestimateestimate Average growth 2019/20 – 2022/23 Learning and culture385.6396.4 Health222.0229.7 Social development284.5309.5 Community development201.7212.3 Economic development198.9211.5 Peace and security214.4217.0 General public services66.370.0 Payments for financial assets65.273.6 4.0% 5.1% 6.2% 6.3% 6.6% 2.2% 3.7% Allocated expenditure1 638.51 720.2 Debt-service costs205.0229.3 Contingency reserve–5.0 12.3% Consolidated expenditure11 843.51 954.4 5.1%

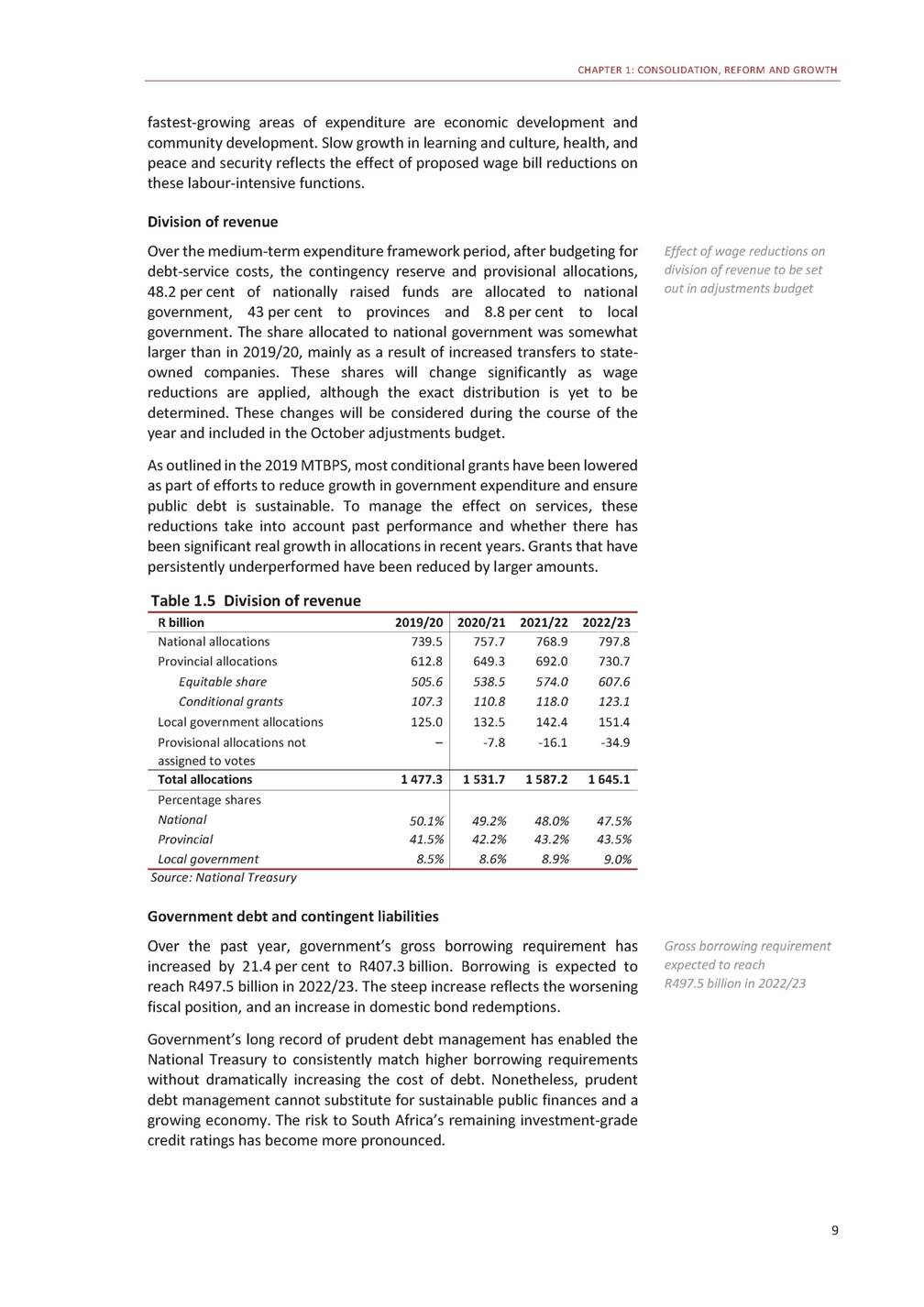

CHAPTER 1: CONSOLIDATION, REFORM AND GROWTH fastest-growing areas of expenditure are economic development and community development. Slow growth in learning and culture, health, and peace and security reflects the effect of proposed wage bill reductions on these labour-intensive functions. Division of revenue Over the medium-term expenditure framework period, after budgeting for debt-service costs, the contingency reserve and provisional allocations, 48.2 per cent of nationally raised funds are allocated to national government, 43 per cent to provinces and 8.8 per cent to local government. The share allocated to national government was somewhat larger than in 2019/20, mainly as a result of increased transfers to state-owned companies. These shares will change significantly as wage reductions are applied, although the exact distribution is yet to be determined. These changes will be considered during the course of the year and included in the October adjustments budget. As outlined in the 2019 MTBPS, most conditional grants have been lowered as part of efforts to reduce growth in government expenditure and ensure public debt is sustainable. To manage the effect on services, these reductions take into account past performance and whether there has been significant real growth in allocations in recent years. Grants that have persistently underperformed have been reduced by larger amounts. Effect of wage reductions on division of revenue to be set out in adjustments budget Table 1.5 Division of revenue Source: National Treasury Government debt and contingent liabilities Over the past year, government’s gross borrowing requirement has increased by 21.4 per cent to R407.3 billion. Borrowing is expected to reach R497.5 billion in 2022/23. The steep increase reflects the worsening fiscal position, and an increase in domestic bond redemptions. Government’s long record of prudent debt management has enabled the National Treasury to consistently match higher borrowing requirements without dramatically increasing the cost of debt. Nonetheless, prudent debt management cannot substitute for sustainable public finances and a growing economy. The risk to South Africa’s remaining investment-grade credit ratings has become more pronounced. Gross borrowing requirement expected to reach R497.5 billion in 2022/23 9 R billion2019/20 2020/21 2021/22 2022/23 National allocations739.5 Provincial allocations612.8 Equitable share505.6 Conditional grants107.3 Local government allocations125.0 Provisional allocations not– assigned to votes 757.7768.9797.8 649.3692.0730.7 538.5574.0607.6 110.8118.0123.1 132.5142.4151.4 -7.8-16.1-34.9 Total allocations1 477.3 1 531.71 587.21 645.1 Percentage shares National 50.1% Provincial 41.5% Local government 8.5% 49.2%48.0%47.5% 42.2%43.2%43.5% 8.6%8.9%9.0%

2020 BUDGET REVIEW Table 1.6 Projected state debt and debt-service costs Source: National Treasury Financial position of public-sector institutions The financial performance of state-owned companies has deteriorated sharply. Liability growth has outpaced that of assets, with a consequent decline in net asset value. This erosion of financial value is largely a result of weak revenue growth, high compensation costs and rapidly growing debt-service costs. The net asset value of the three largest development finance institutions – the Development Bank of Southern Africa, the Industrial Development Corporation and the Land Bank – increased by 4.7 per cent in 2018/19 to R139.4 billion. With the exception of the RAF, the financial positions of the social security funds and the Government Employees Pension Fund are strong. They are able to meet their long-term obligations. Net asset value of state-owned companies has declined sharply in recent years Table 1.7 Combined financial position of public institutions R billion/net asset value 2016/17 2017/18 2018/19 State-owned companies Development finance institutions1 Social security funds Other public entities2 354.0 126.8 1.0 674.9 362.1 133.1 -27.0 719.0 342.0 139.4 -90.2 751.7 1. Institutions listed in schedule 2 of the PFMA 2. State-owned institutions without a commercial mandate and listed in either schedule 1 or 3 of the PFMA such as the National Library of South Africa Source: National Treasury Budget documentation The 2020 Budget Review accompanies several other documents and submissions tabled in Parliament on Budget Day. These include: • • • • The Budget Speech The Division of Revenue Bill The Appropriation Bill The Estimates of National Expenditure. These and other fiscal and financial publications, including the People’s Guide to the Budget, are available at www.treasury.gov.za. 10 R billion/percentage of GDP2019/20 2020/212021/222022/23 Gross loan debt3 176.1 61.6% Debt-service costs205.0 4.0% 3 561.73 978.14 383.6 65.6%69.1%71.6% 229.3258.5290.1 4.2%4.5%4.7%

2 Economic outlook Overview MThis remains government’s core policy objective. Higher growth ore rapid and sustained economic growth is the central Decisions required that build confidence and boost investment to create jobs and raise growth requirement to build a prosperous and equitable South Africa. would also reduce pressure on the public finances. Achieving this requires decisive steps to build confidence, promote investment and employment, reduce anti-competitive practices and eliminate regulatory blockages. The economic outlook has weakened since the 2019 MTBPS, following lower-than-expected growth in the second half of the year. Real GDP is estimated to have grown by only 0.3 per cent in 2019, partly as a result of electricity supply failures. Weak growth translated into a record unemployment rate of 29.1 per cent in the second half of 2019. Economic growth projections have been revised down to 0.9 per cent in 2020, rising to just 1.6 per cent in 2022. Electricity shortages are expected to constrain the economy over the forecast period. Global growth is expected to rise moderately over the forecast period, but considerable downside risks remain. The outlook for South Africa’s key trading partners has weakened in recent months. 11 In brief •Since the 2019 Medium Term Budget Policy Statement (MTBPS), economic growth has been revised lower, in part due to electricity supply shortages. Real GDP is expected to grow at 0.9 per cent in 2020. •Global growth is expected to rise moderately over the forecast period, but considerable downside risks remain. The outlook for South Africa’s key trading partners has weakened in recent months. •Government has announced urgent reforms in the electricity sector to ensure adequate supply of power for businesses and households. •Raising South Africa’s economic growth rate requires structural reforms, including substantial changes in the network industries, to reduce costs and encourage investment across the economy.

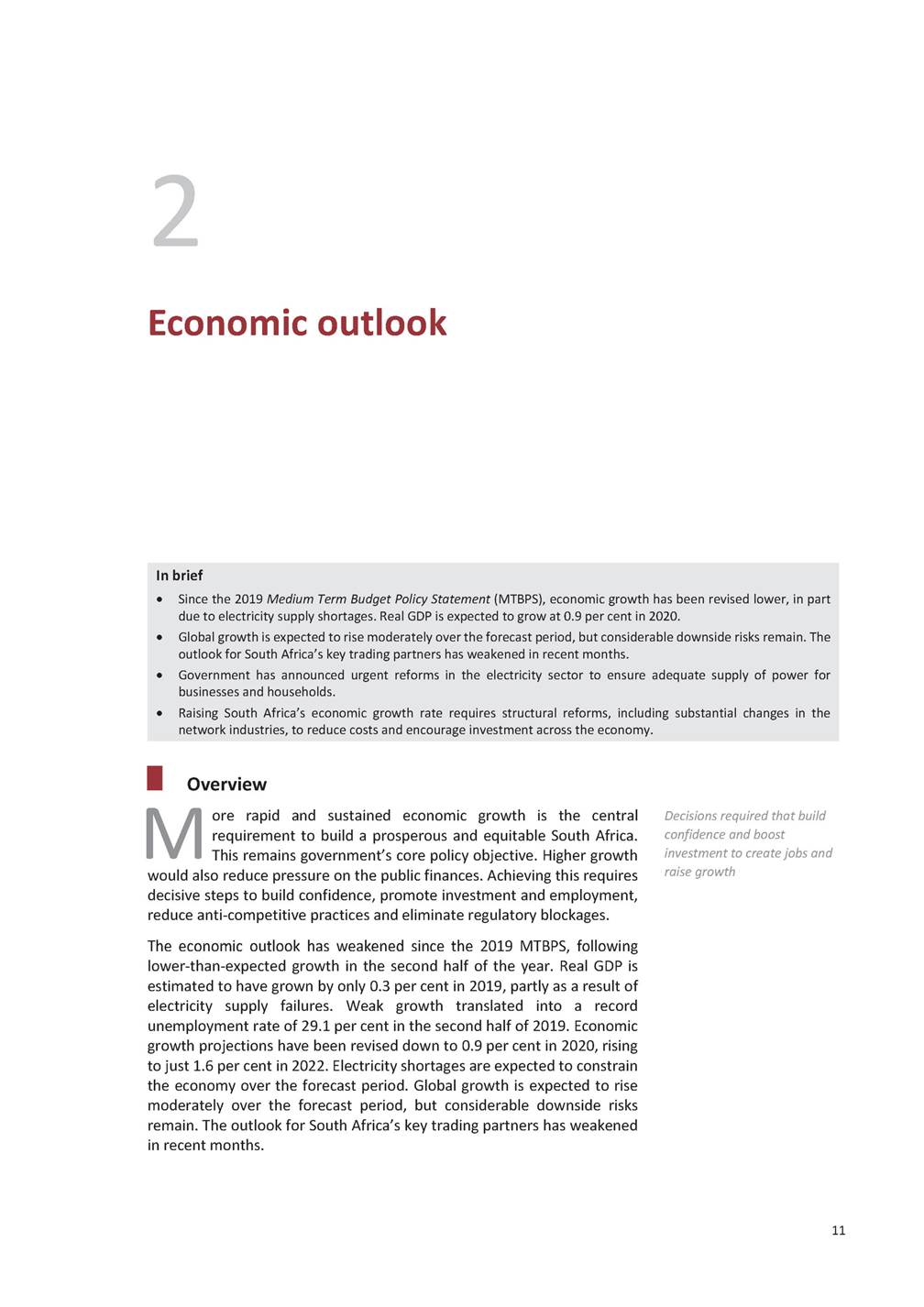

2020 BUDGET REVIEW To jump-start growth, South Africa requires stronger investment by, and partnerships with, the private sector. Recent network industry failures – in particular in electricity, but also in ports – have increased the cost of doing business. Yet these failures also offer opportunities to draw in private-sector skills and investment, reduce operating costs and build confidence. The 2019 MTBPS noted that policy certainty and a conducive business environment are critical to support the confidence of business and households. South Africa’s monetary policy framework has provided certainty. Enhancing the state’s contribution to the economy requires greater spending efficiency and a shift in the composition of spending from consumption towards capital infrastructure. It also requires a clear vision for the role of state-owned companies within a robust framework for financial and operational management. The macroeconomic framework needs to be complemented by a range of reforms that are within government’s control, many of which do not require significant funding. The overriding priority is to enact structural reforms that enable the economy to break from the spiral of low growth and deteriorating public finances. Private-sector skills and investment can expand electricity generation and improve ports’ performance 60 15 Reforms to boost confidence and investment The foundations for economic growth include prudent and credible fiscal and monetary policy, reliable electricity supply, a well-functioning financial system and respect for the rule of law. The speed at which an economy can grow will then be determined by factors affecting the costs of doing business, including the regulatory environment, support for innovation and competition, and the quality and cost of infrastructure. As highlighted in the 2019 MTBPS, government is focused on structural reforms to support competitiveness, investment and employment, by: Structural reforms needed that lower costs of living and of doing business • Reducing costs for households and businesses by modernising and reforming network industries, restructuring inefficient state-owned companies and inviting private-sector participation. Increasing exports through evidence-based, export-orientated industrial policy, and supporting labour-intensive sectors such as agriculture and tourism. Promoting competition and supporting small business. • • 12 Index level 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 Annual growth (per cent) Figure 2.1 Government spending compositionFigure 2.2 Confidence and private investment RMB/BER Business Confidence Index Private investment (RHS) 50 10 5 40 0 30 -5 20 -10 -15 10 -20 0 -25 Source: Statistics South Africa and National Treasury calculationsSource: Global Insight

CHAPTER 2: ECONOMIC OUTLOOK Initial steps to expand electricity supply Facilitating faster private-sector involvement in the power sector will catalyse confidence and growth more broadly. The President announced a set of urgent reforms to address the Eskom crisis in his February 2020 State of the Nation Address. To facilitate large-scale additional power production, the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy is assessing information to procure 2 000 to 3 000 megawatts of power through its risk mitigation programme. This power will be connected to the national grid within three to 12 months from approval. Efforts are under way to acquire additional electricity from existing independent power producers (IPPs). Government has committed to open bid window 5 and make it possible for municipalities in good financial standing to buy electricity from IPPs. These efforts will be supported by operational changes announced by the new Eskom CEO, which include separating the utility into three divisions, resuming scheduled maintenance practices, fixing defects at Medupi and Kusile, and buying energy from entities with excess supply. Eskom will also reinstate its demand management strategy, with a clear schedule that allows users to mitigate the most disruptive effects of unplanned outages. Awareness campaigns will help to reduce pressure on the national grid. A commitment to minimum response times by the National Energy Regulator of South Africa would be supported by introducing simpler, standardised and more transparent licensing requirements for connecting to the grid. This in turn would support the emergence of smaller electricity providers. Efforts are under way to acquire additional electricity from existing IPPs Simpler and more transparent licensing arrangements needed from energy regulator Clearing blockages in transport, logistics and communications In other network industries, work continues to expand access, draw in private investment and reduce the costs of doing business. These include: • Rail transport reforms – In November 2019, Cabinet approved the Economic Regulation of Transport Bill for submission to Parliament. The bill – which consolidates economic regulations for the aviation, marine, rail and road transport sectors – will improve third-party access to rail. • Spectrum licensing – The broadband spectrum licensing plan was released in November 2019. Government is acting to make additional spectrum available from analogue television users. 13 The economic impact of Eskom supply disruptions Eskom, which has a near monopoly on South Africa’s electricity supply, is taking a large toll on the economy. Industry estimated that power cuts caused losses of about 0.1 per cent of GDP in the fourth quarter of 2019. However, without intervention, the impact of supply disruptions on growth will be greater in 2020. Power cuts – even scheduled ones – restrict production and investment, lower trade, increase the cost of doing business and put pressure on profits and employment. This in turn tends to reduce technology uptake and modernisation, particularly in small businesses. An uncertain and declining supply of electricity also contributes to low levels of confidence and investment, as well as lost capacity due to damage from power surges. The size of Eskom’s balance sheet and its dominance in the energy sector affect the cost of borrowing for government, which in turn affects the cost of borrowing for the entire economy. Taken together, these factors structurally lower South Africa’s competitiveness, employment and exports.

2020 BUDGET REVIEW Supporting competition, trade and policy certainty Actions to boost investment, trade and policy certainty include: • Reforms to benefit small business – The Companies and Intellectual Property Commission website now includes a single platform for company registration, including registering with social security funds and the South African Revenue Service. In addition, the Competition Commission made rulings in December 2019 that imply a decrease in data costs. Investment promotion – In support of the President’s initiative, R664 billion of investment commitments have been made. South Africa’s foreign-exchange control system will be modernised over the next year to support investment and the country’s position as a hub on the continent, as outlined in Annexure E. The Upstream Petroleum Development Bill, which will guide oil and gas exploration and production, was released for public comment in December 2019. • • Industrial policy – Government and industry continue to work master plans to raise growth and exports in 15 key sectors. on Maximising the long-term growth impact of the fiscal framework Government is exploring ways to maximise the long-term growth impact of the fiscal framework. This includes: • Improving the composition of spending, by rebalancing spending towards capital expenditure rather than compensation. 14 A just transition: Avoiding short-term policy responses that harm long-term growth South Africa’s low growth levels and high unemployment reinforce the desire to protect existing industries and jobs. All governments consider a range of trade-offs in such matters. However, policy decisions should not lock the economy into production patterns that will limit long-term growth. To achieve higher living standards, South Africa needs to adjust to global market demand. Climate change is starting to shape the manner in which the largest markets regulate imported and domestic products. Support for industries with high carbon emissions is likely to threaten long-term export demand and growth, and could lock South Africa into a position of a low-value exporter. Climate challenges also represent opportunities to generate new economic activity. Jobs and investment can be created by drawing on private-sector skills and capital, while demand for carbon-intensive products can be managed with incentives and penalties. Industrial policy should support businesses that can respond to these challenges – including producing new food technologies, electric cars, renewable-energy equipment, or energy-and water-saving devices. Targeted social interventions, including re-skilling and financial support, should be directed to workers in sunset industries, rather than providing support to affected companies. Future-focused policy that takes cognisance of climate change would support efforts to raise youth employment, as announced in the State of the Nation Address, in sectors such as business-process outsourcing, tourism and technology. Swift regulatory action to clear backlogs and modernise ports Commercial ports’ efficiency has declined sharply over the past year. This is the combined result of poor management, inadequate maintenance and resulting equipment failures, and industrial action at container terminals. Delays in modernising ports and digitising operations have compounded these problems. Backlogs for those importing and exporting container cargo have increased sharply, raising costs and damaging export competitiveness. South Africa needs a modern and efficient ports system to reduce the costs of living and of doing business, and to maintain its position as one of Africa’s main trading hubs. Swift and decisive regulatory action is needed. The corporatisation of the National Ports Authority, provided for in the National Ports Act (2005), should be accelerated. The authority, which regulates ports operators and undertakes infrastructure investment, currently operates as a division of Transnet. Corporatising the authority should allow for better regulation of all port operators, including Transnet Port Terminals. It would also support greater reinvestment of operating profits back into ports, free from Transnet group considerations.

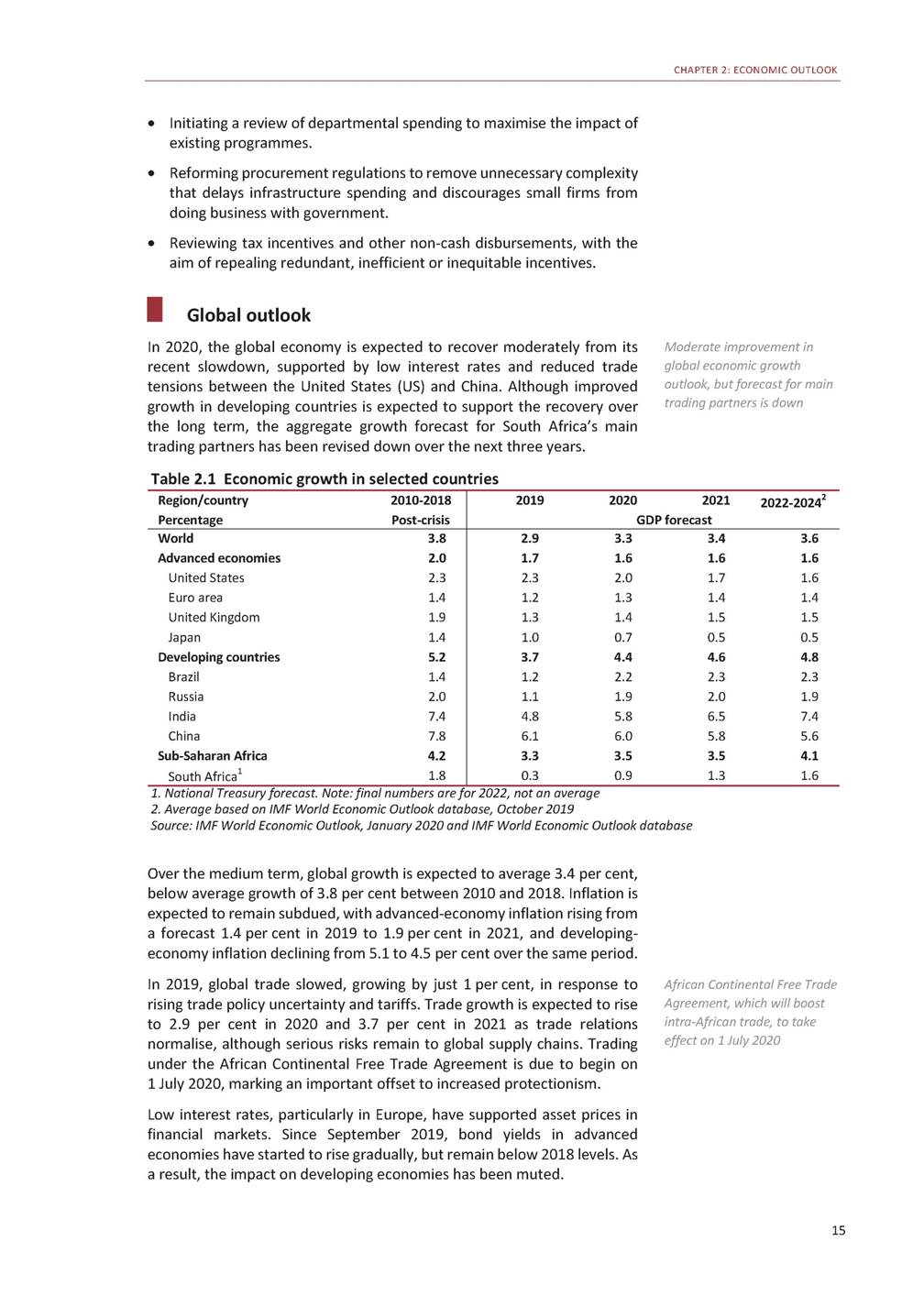

CHAPTER 2: ECONOMIC OUTLOOK • Initiating a review of departmental spending to maximise the impact of existing programmes. Reforming procurement regulations to remove unnecessary complexity that delays infrastructure spending and discourages small firms from doing business with government. Reviewing tax incentives and other non-cash disbursements, with the aim of repealing redundant, inefficient or inequitable incentives. • • Global outlook In 2020, the global economy is expected to recover moderately from its recent slowdown, supported by low interest rates and reduced trade tensions between the United States (US) and China. Although improved growth in developing countries is expected to support the recovery over the long term, the aggregate growth forecast for South Africa’s main trading partners has been revised down over the next three years. Table 2.1 Economic growth in selected countries Moderate improvement in global economic growth outlook, but forecast for main trading partners is down 1. National Treasury forecast. Note: final numbers are for 2022, not an average 2. Average based on IMF World Economic Outlook database, October 2019 Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, January 2020 and IMF World Economic Outlook database Over the medium term, global growth is expected to average 3.4 per cent, below average growth of 3.8 per cent between 2010 and 2018. Inflation is expected to remain subdued, with advanced-economy inflation rising from a forecast 1.4 per cent in 2019 to 1.9 per cent in 2021, and developing-economy inflation declining from 5.1 to 4.5 per cent over the same period. In 2019, global trade slowed, growing by just 1 per cent, in response to rising trade policy uncertainty and tariffs. Trade growth is expected to rise to 2.9 per cent in 2020 and 3.7 per cent in 2021 as trade relations normalise, although serious risks remain to global supply chains. Trading under the African Continental Free Trade Agreement is due to begin on 1 July 2020, marking an important offset to increased protectionism. Low interest rates, particularly in Europe, have supported asset prices in financial markets. Since September 2019, bond yields in advanced economies have started to rise gradually, but remain below 2018 levels. As a result, the impact on developing economies has been muted. African Continental Free Trade Agreement, which will boost intra-African trade, to take effect on 1 July 2020 15 Region/country2010-2018 PercentagePost-crisis 2019202020212022-20242 GDP forecast World3.8 Advanced economies2.0 United States2.3 Euro area1.4 United Kingdom1.9 Japan1.4 Developing countries5.2 Brazil1.4 Russia2.0 India7.4 China7.8 Sub-Saharan Africa4.2 South Africa11.8 2.93.33.43.6 1.71.61.61.6 2.32.01.71.6 1.21.31.41.4 1.31.41.51.5 1.00.70.50.5 3.74.44.64.8 1.22.22.32.3 1.11.92.01.9 4.85.86.57.4 6.16.05.85.6 3.33.53.54.1 0.30.91.31.6

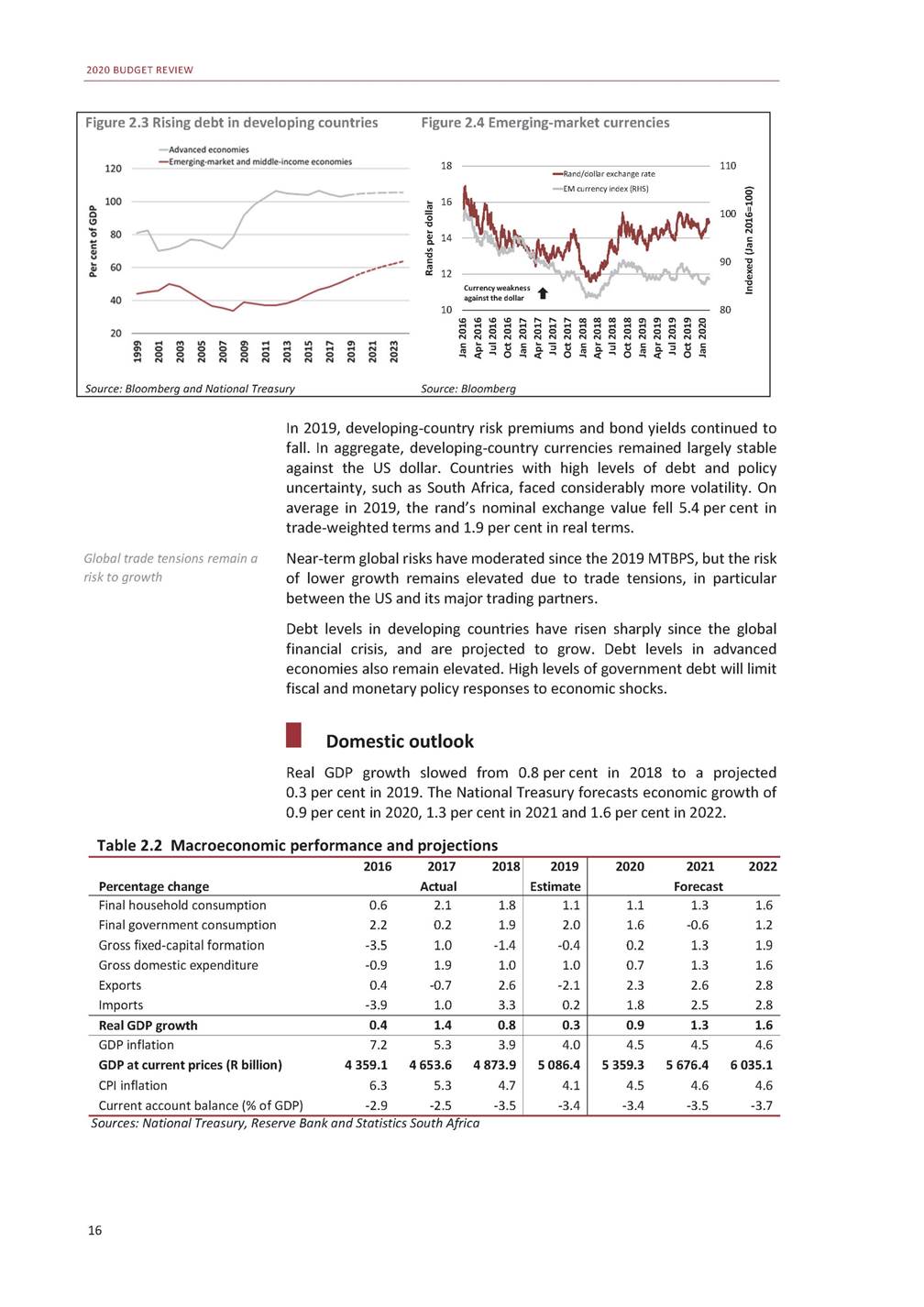

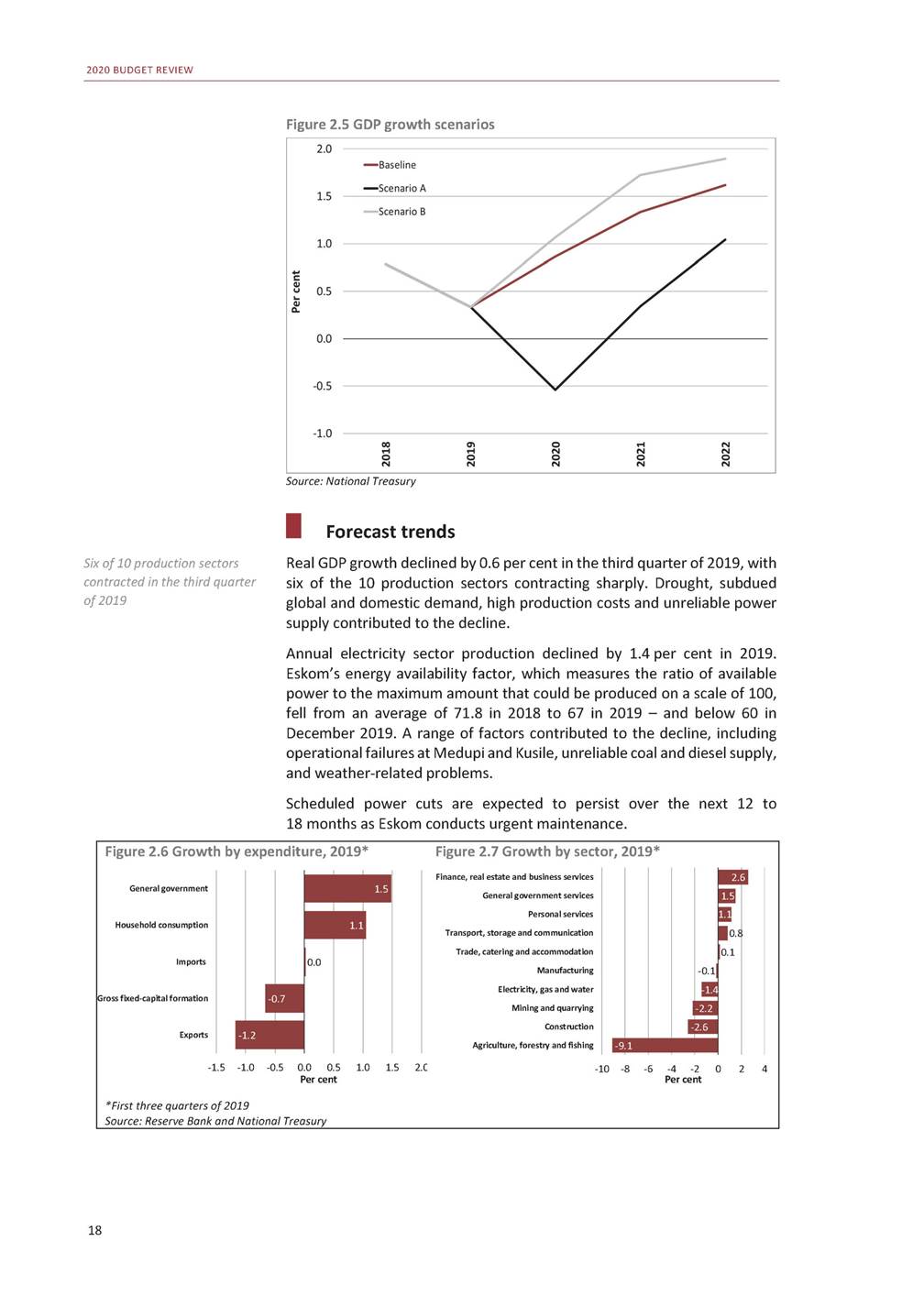

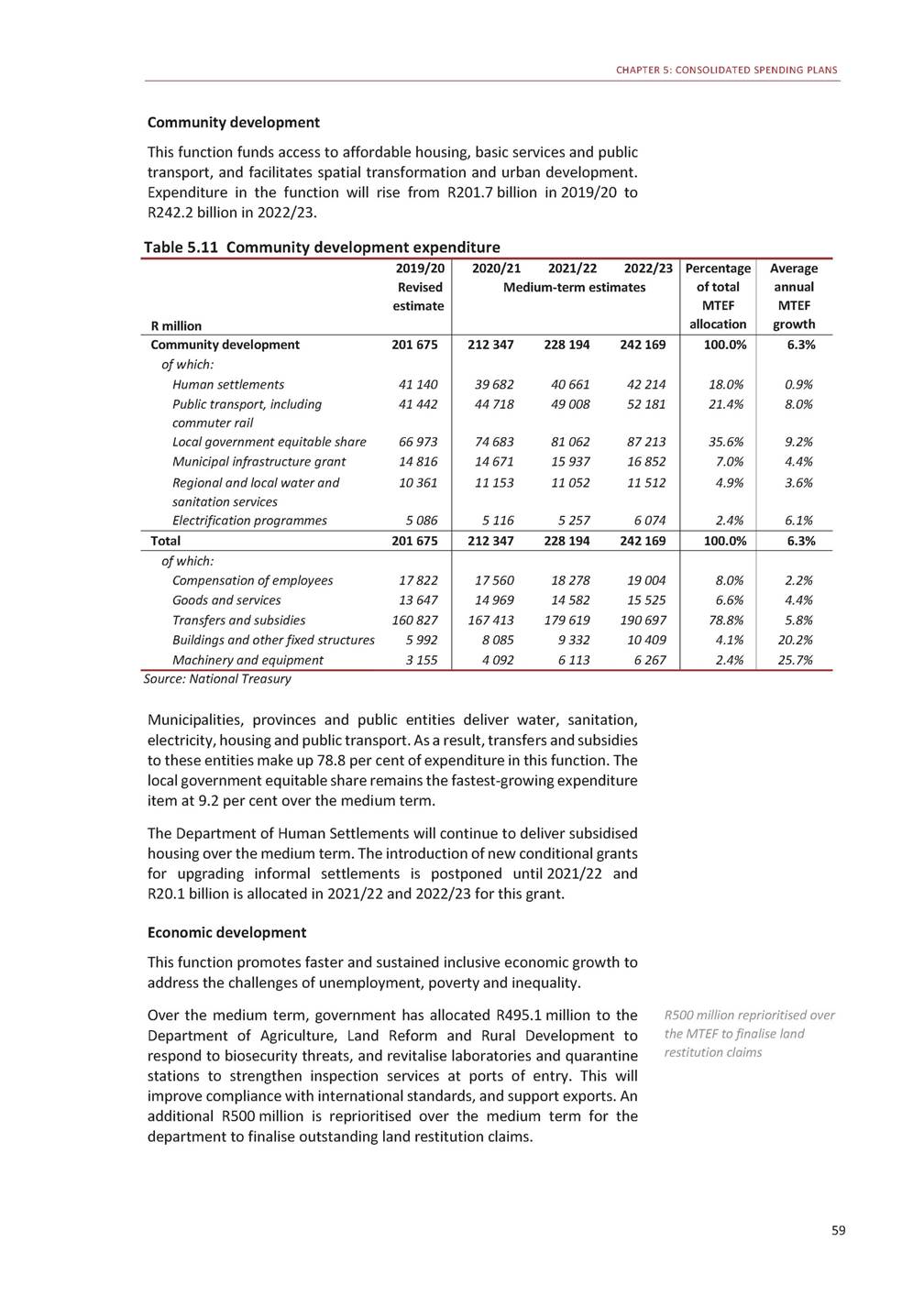

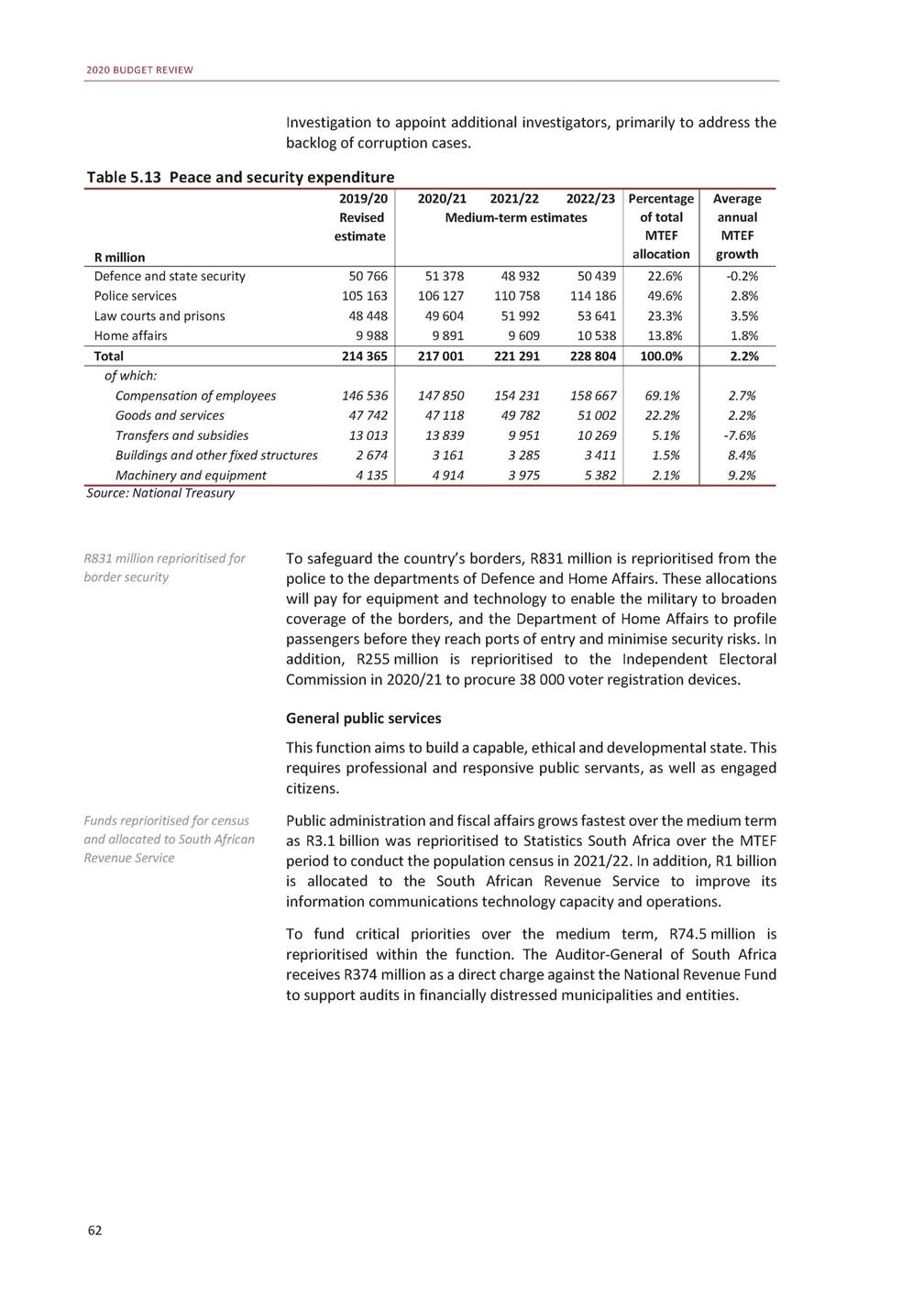

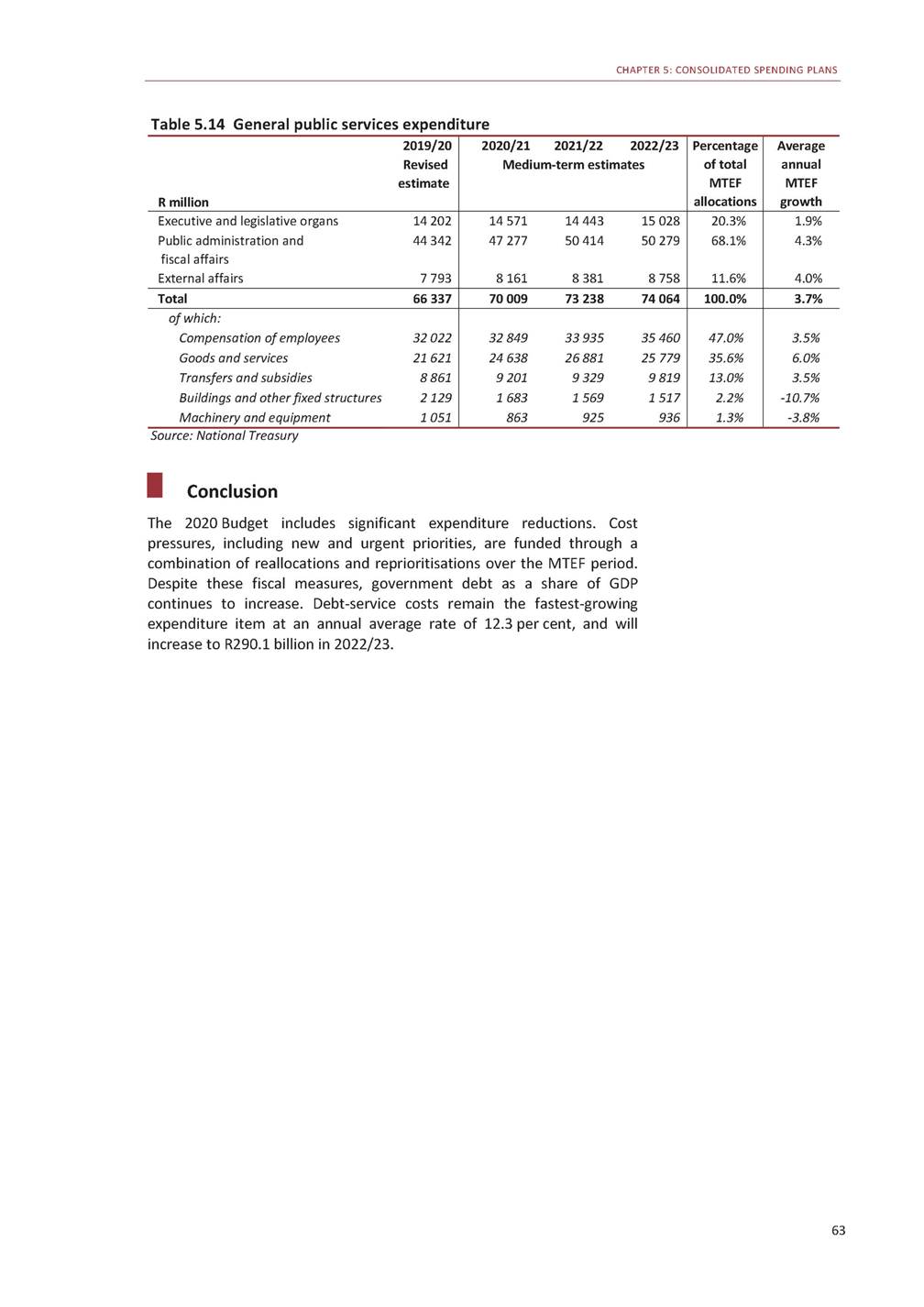

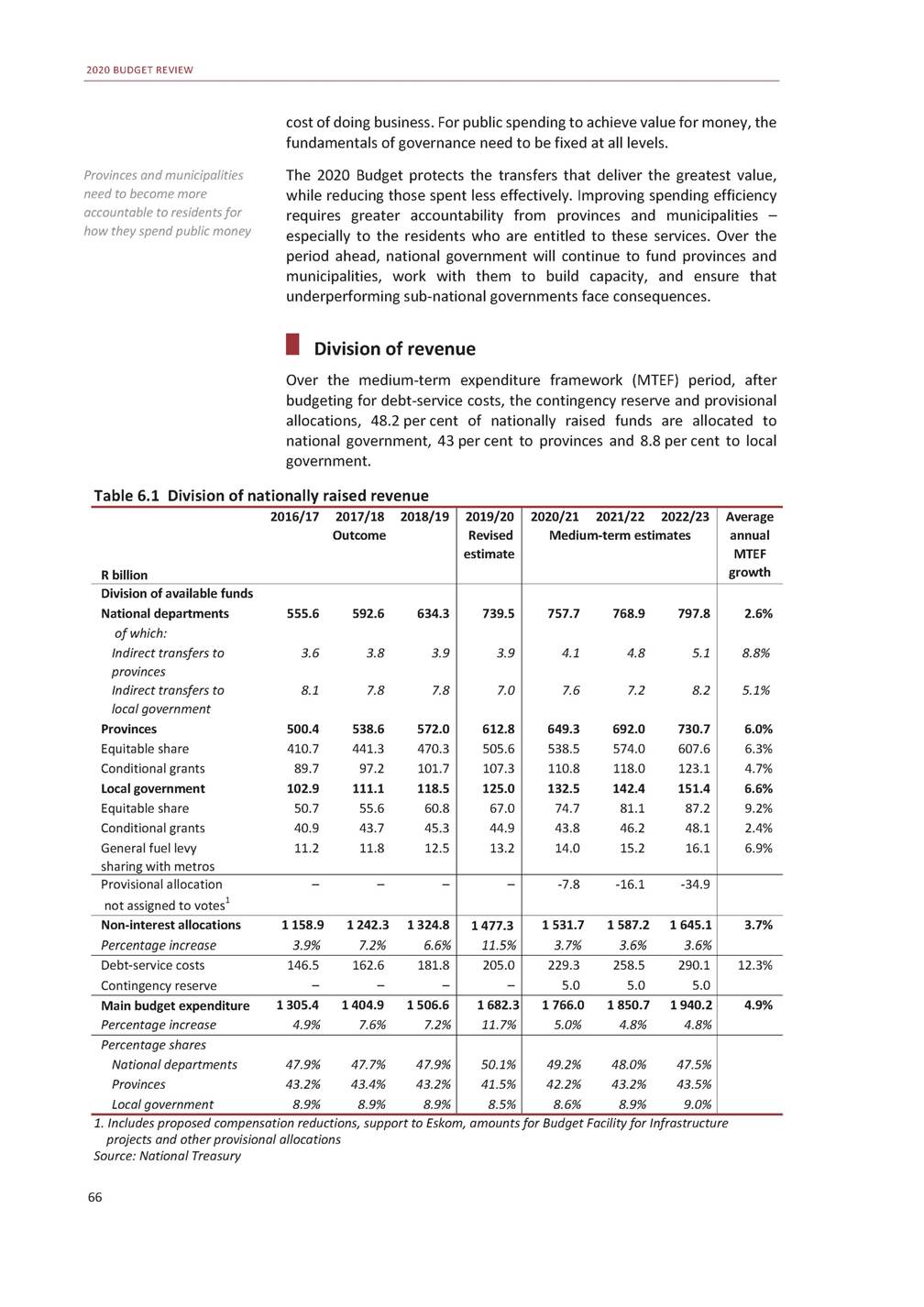

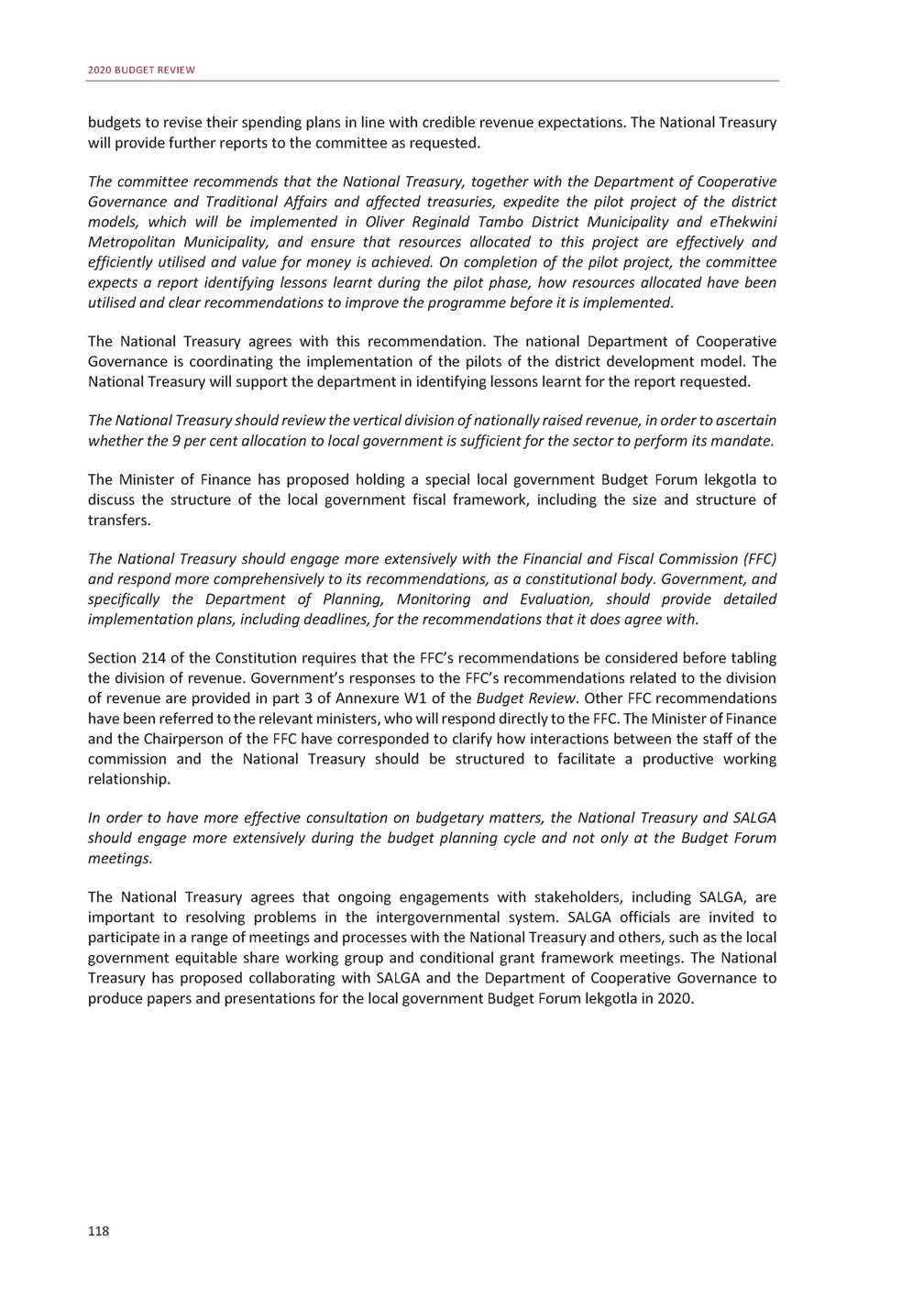

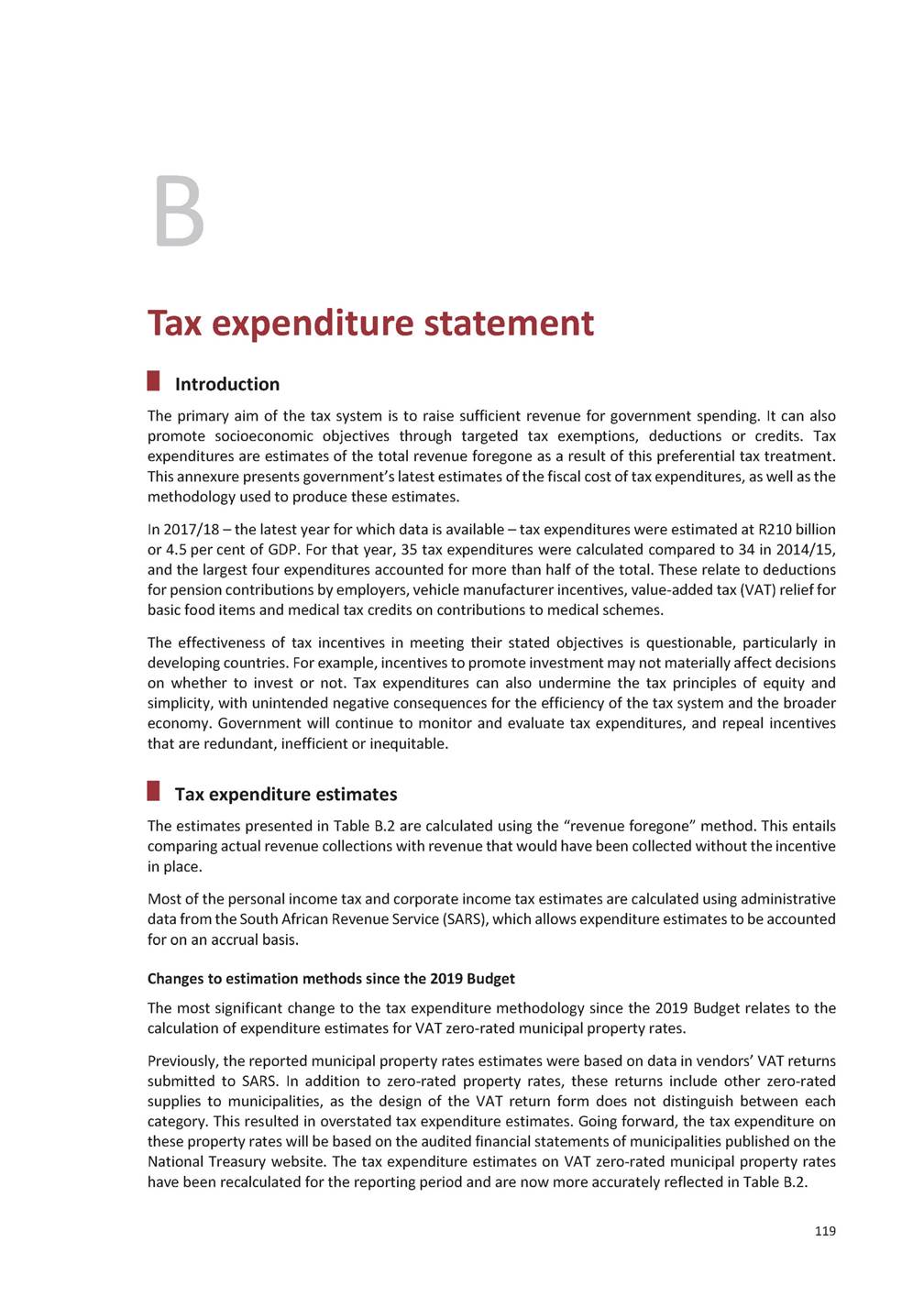

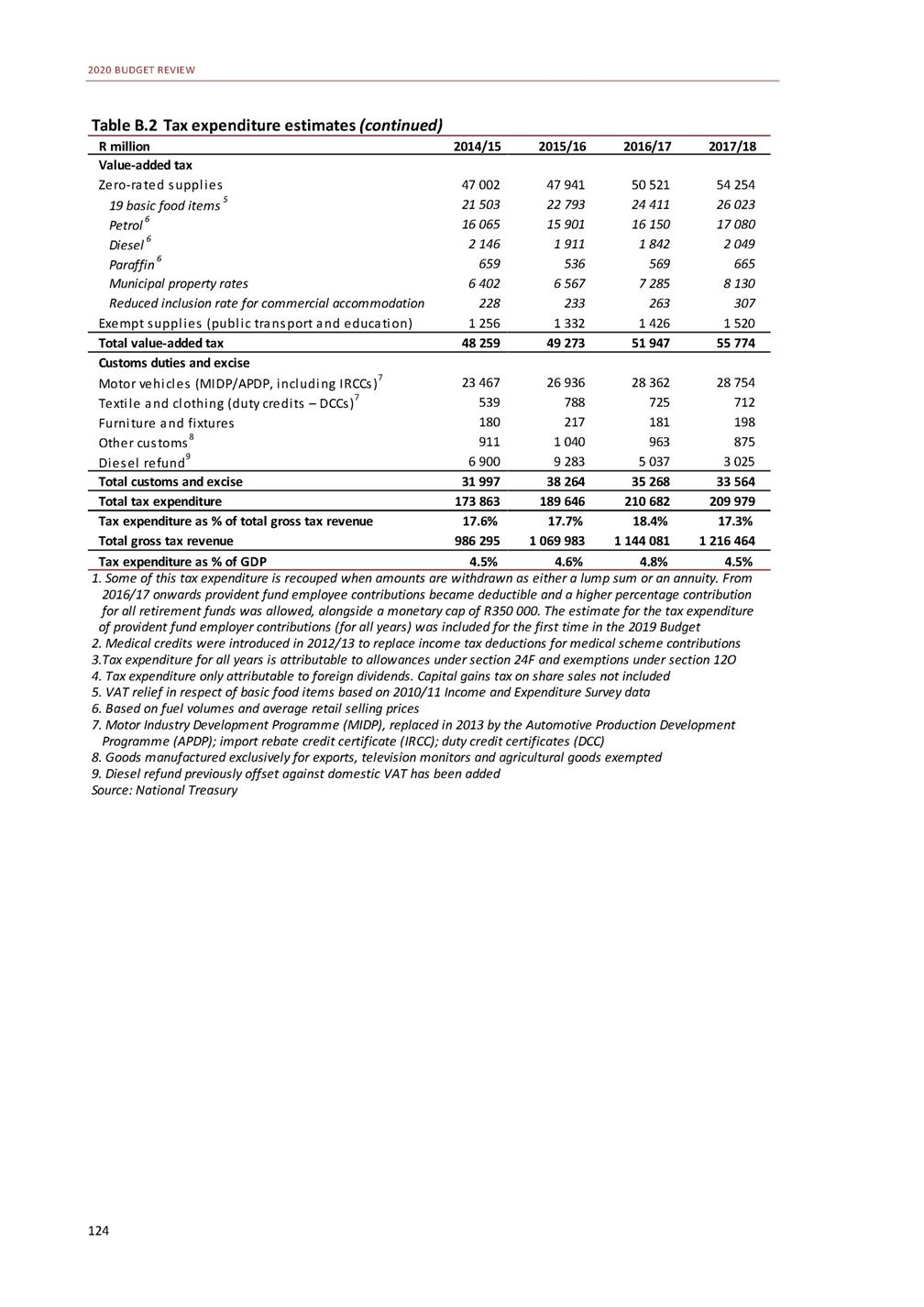

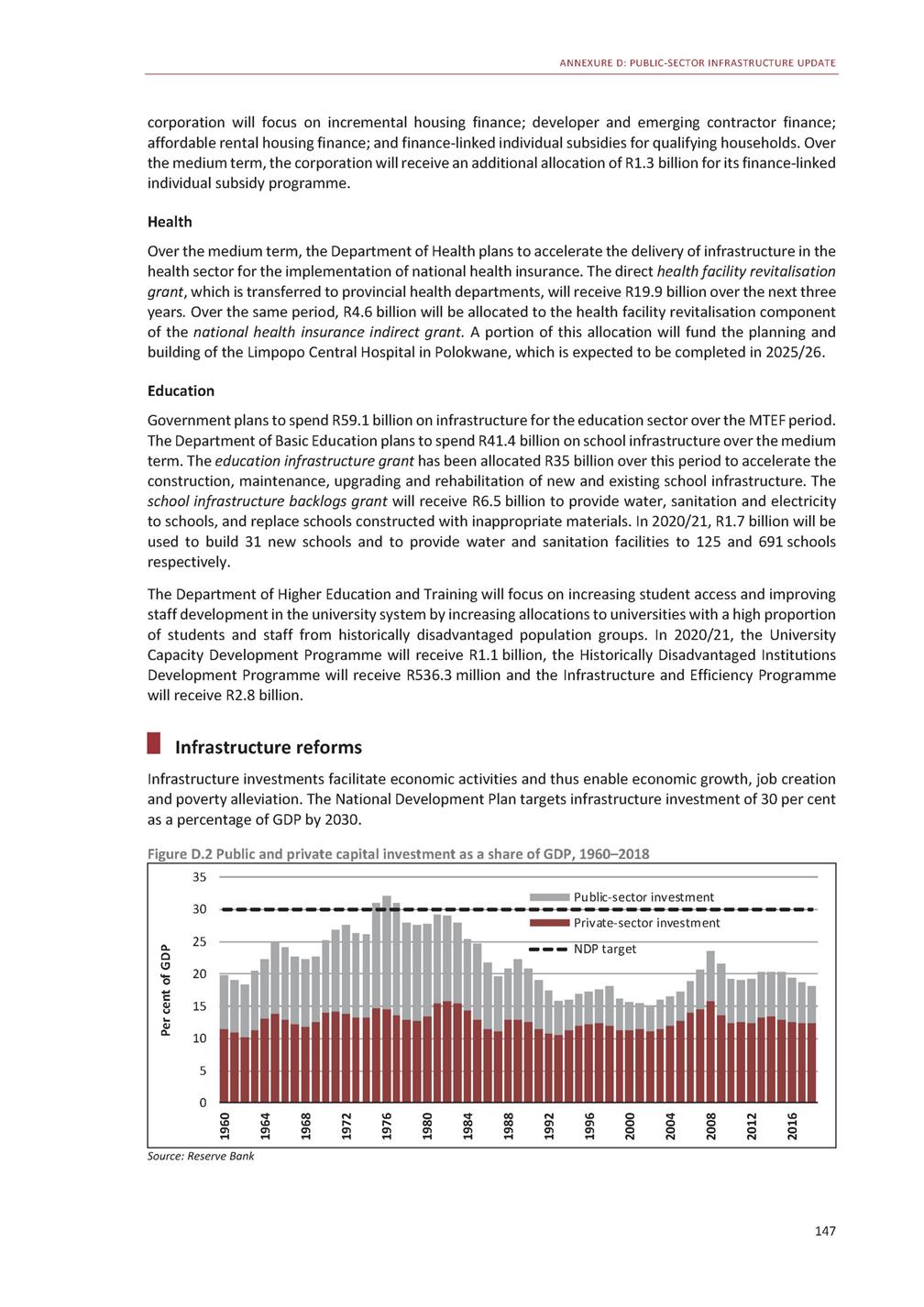

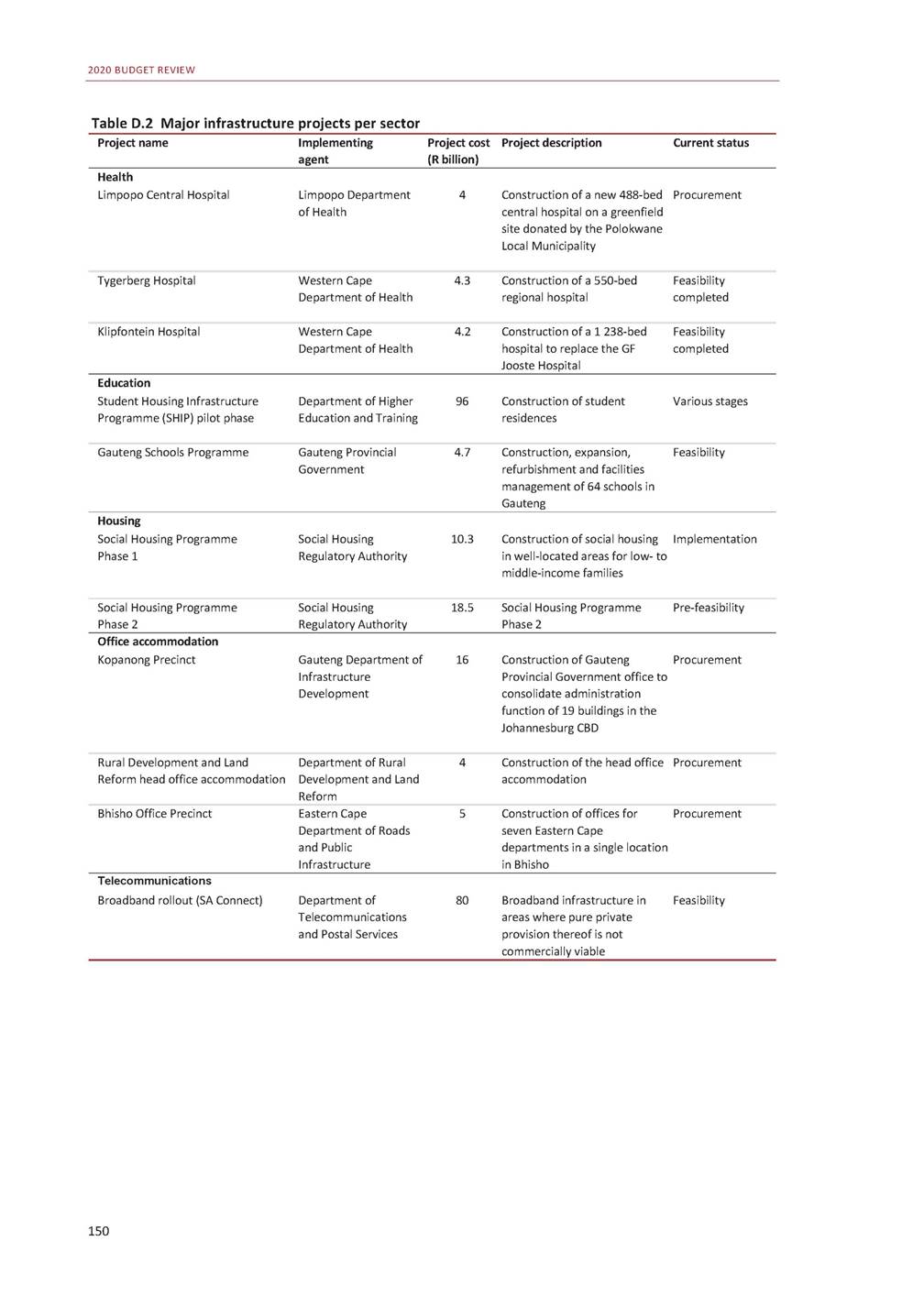

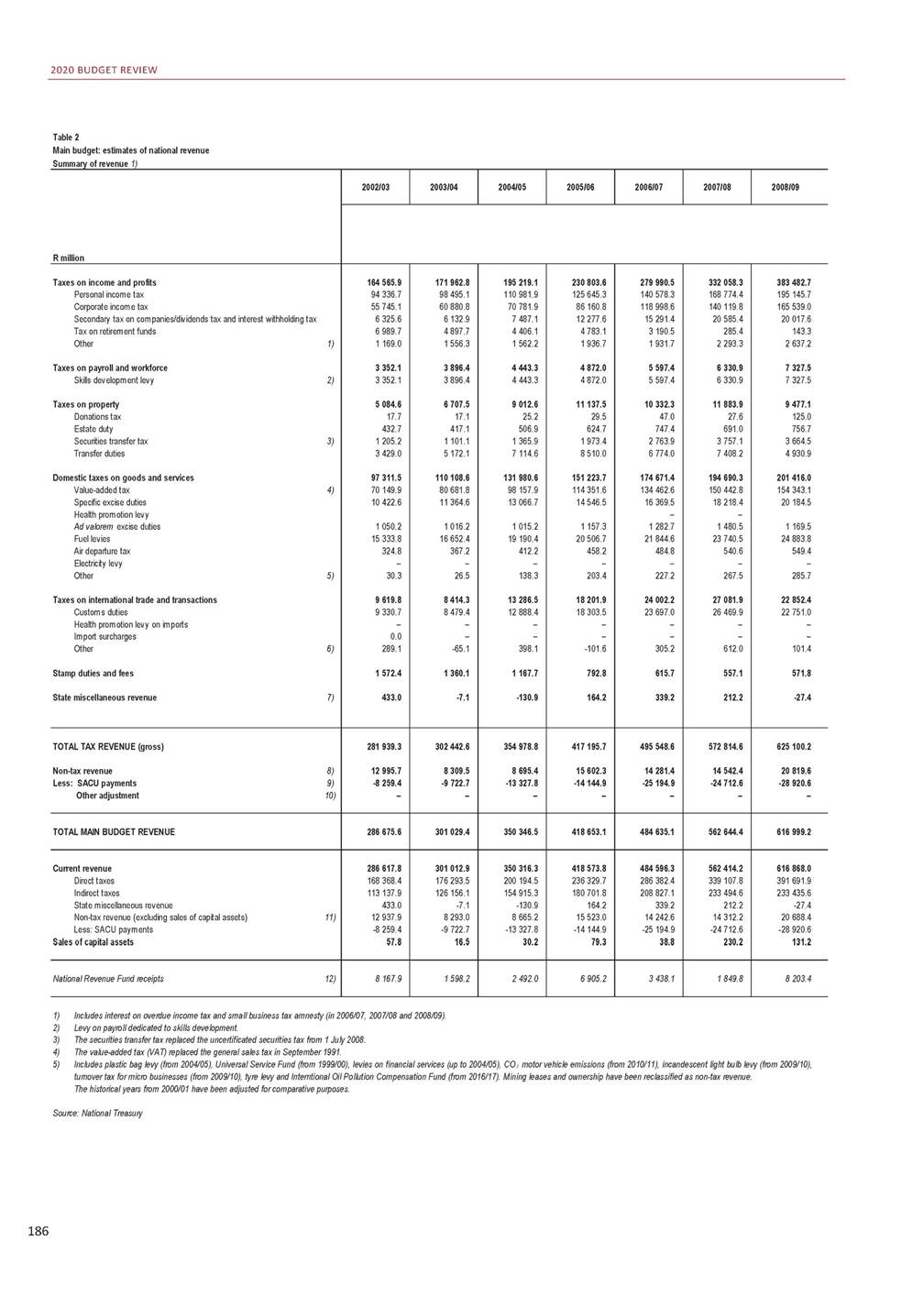

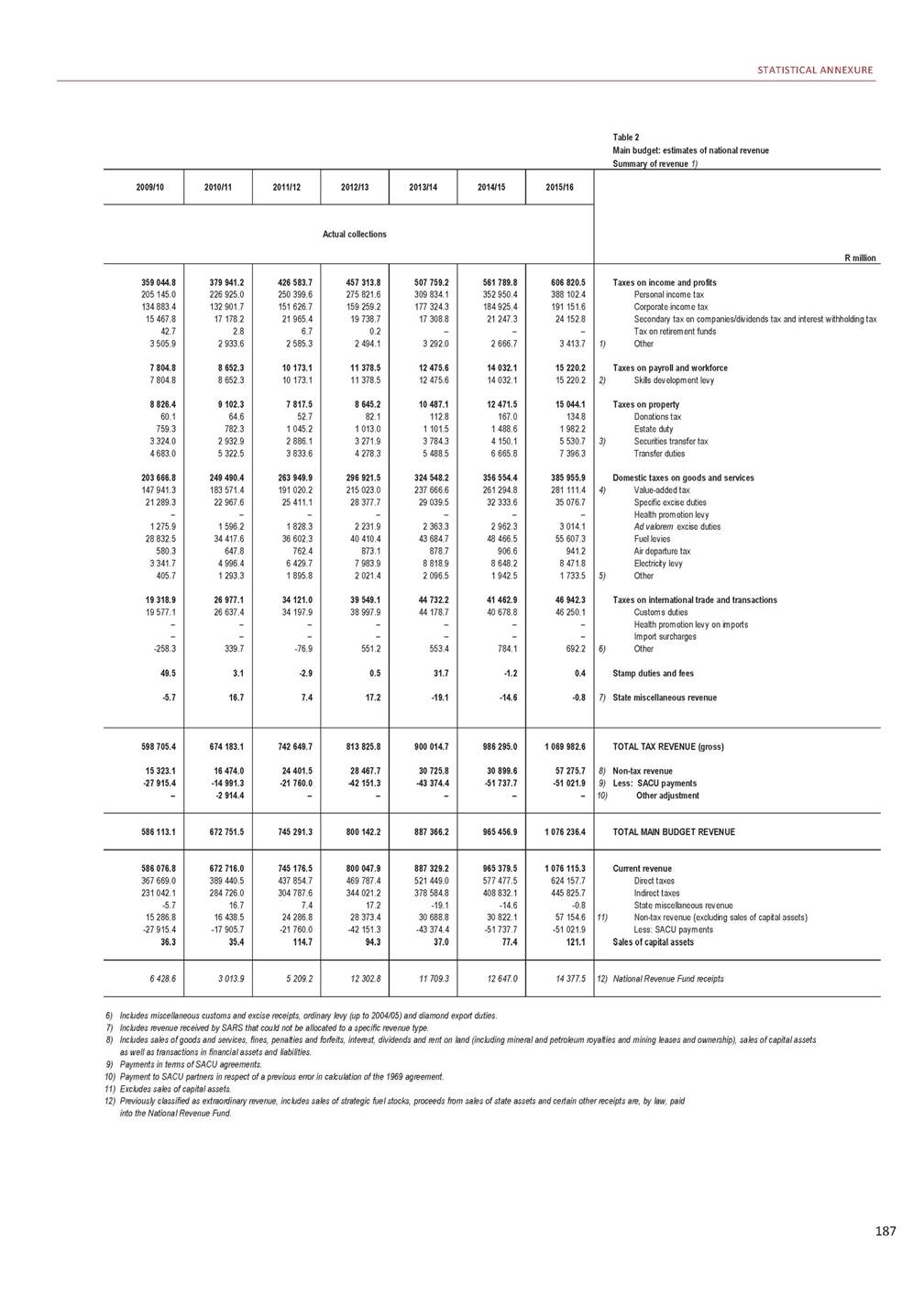

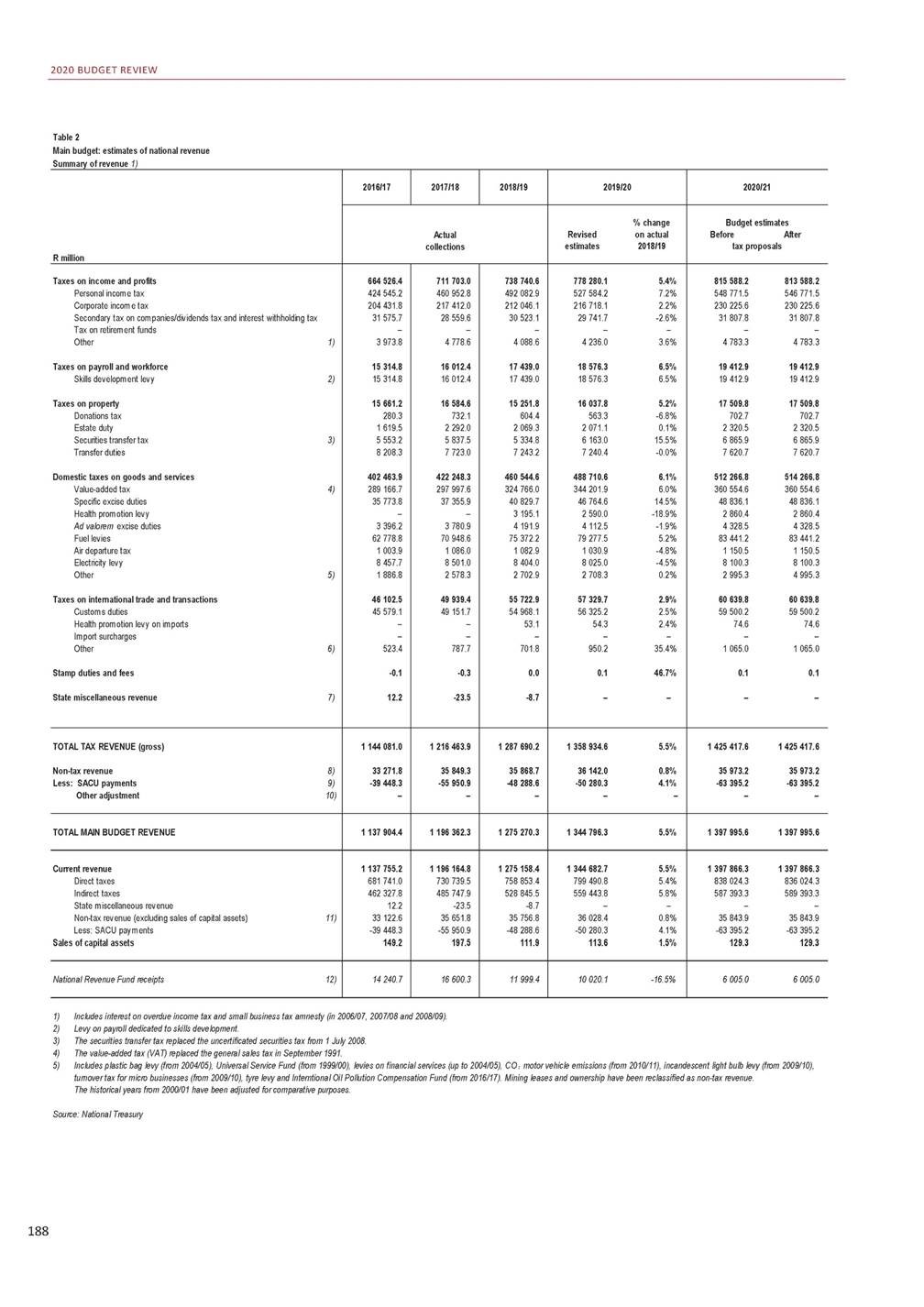

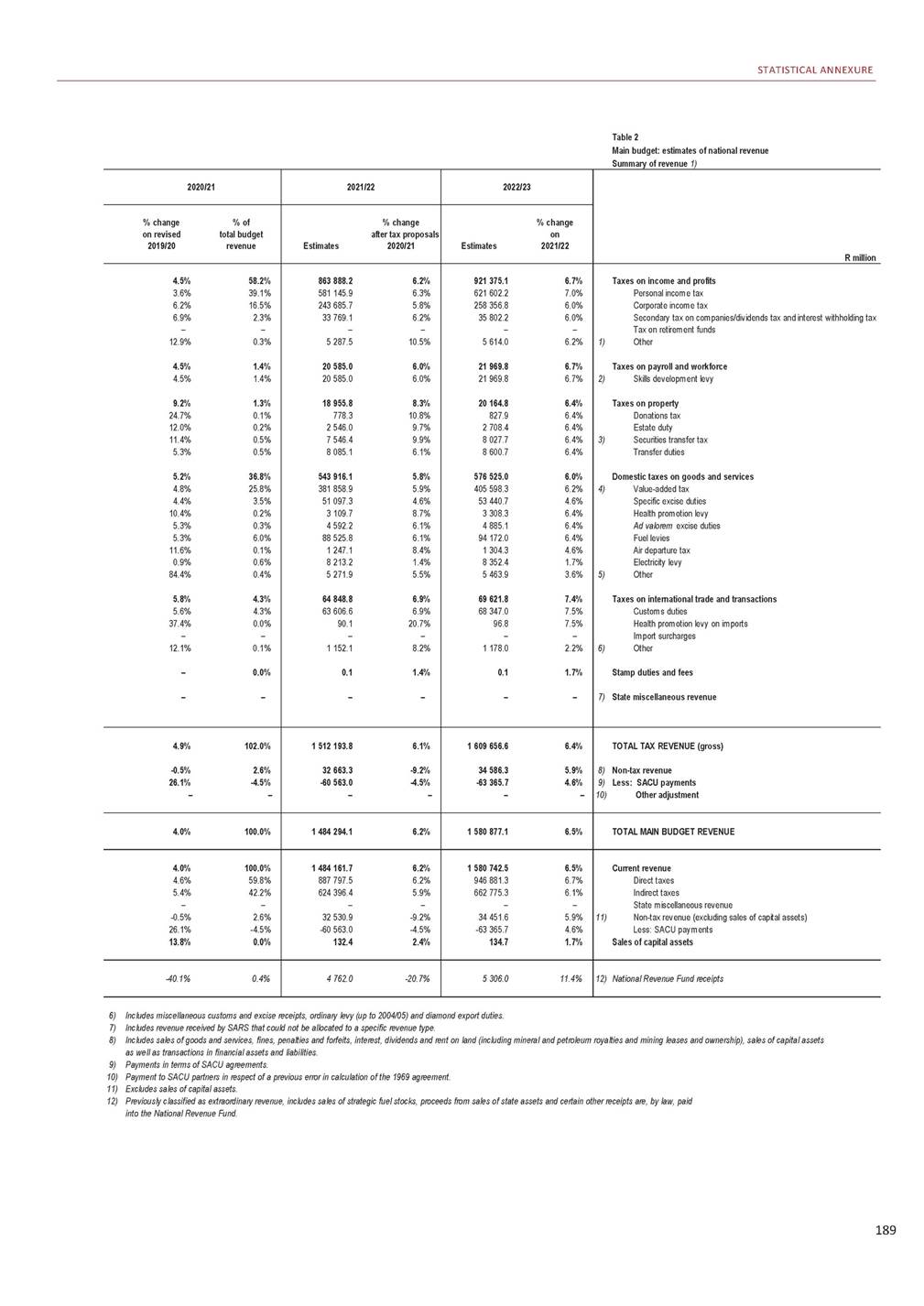

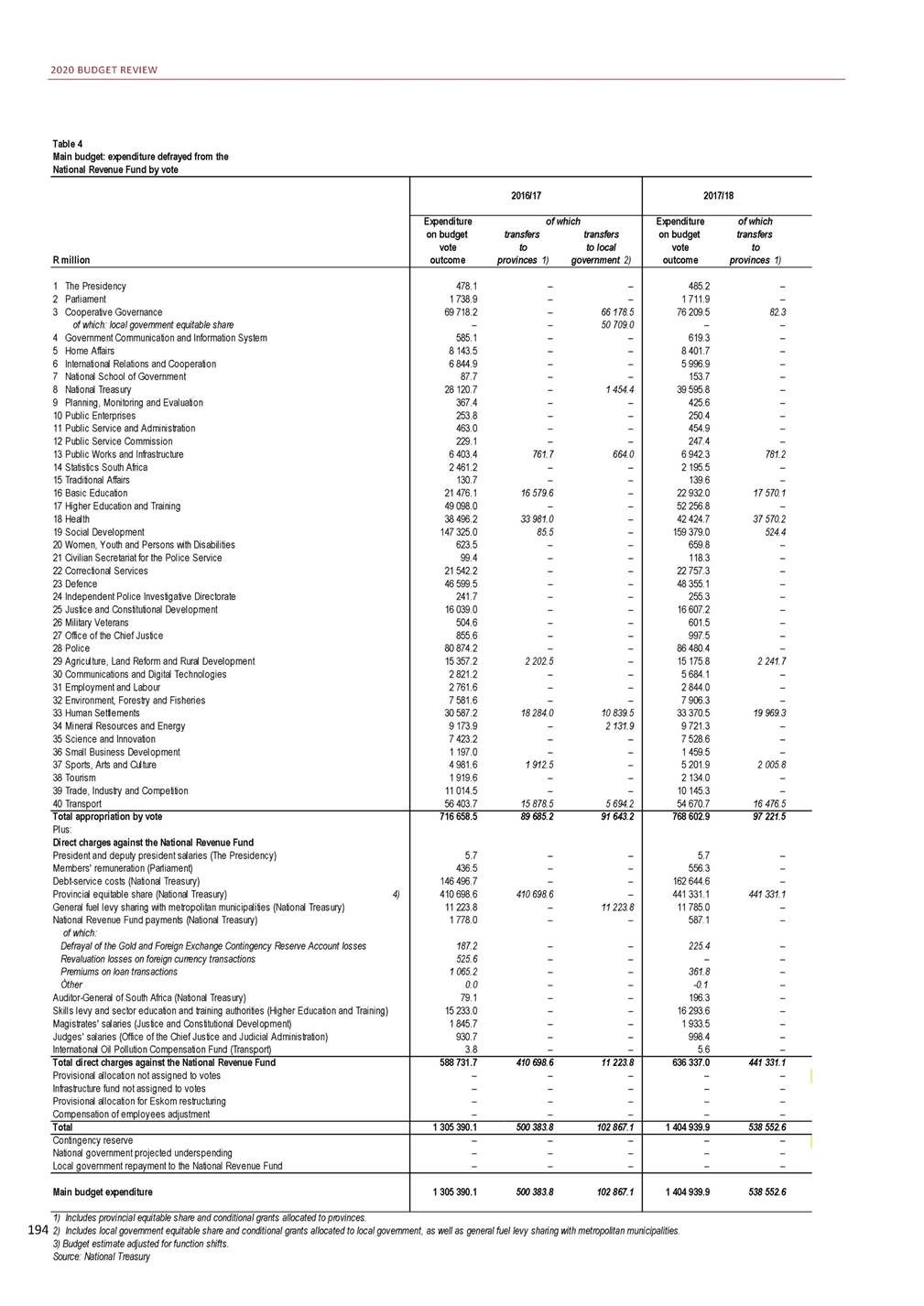

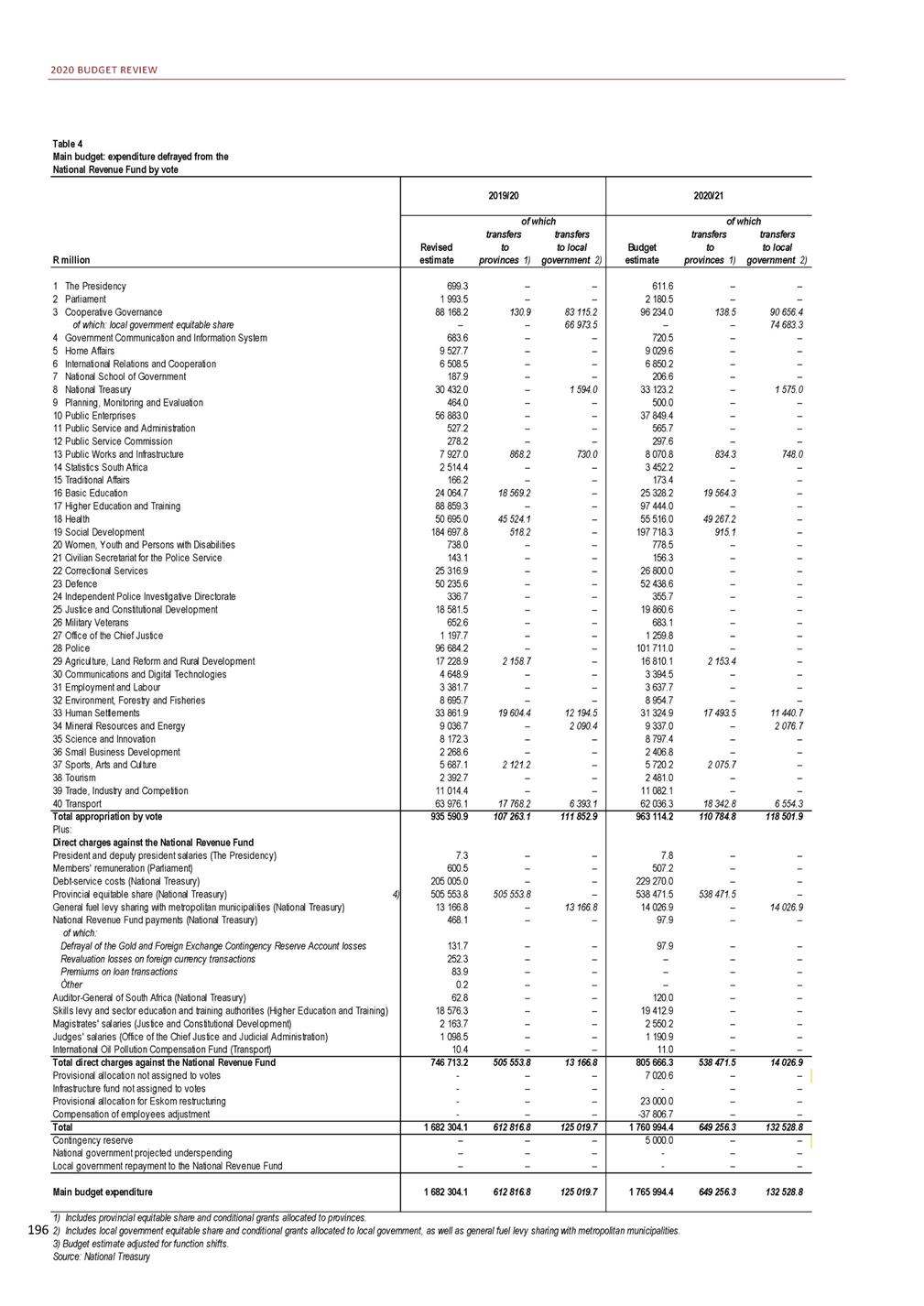

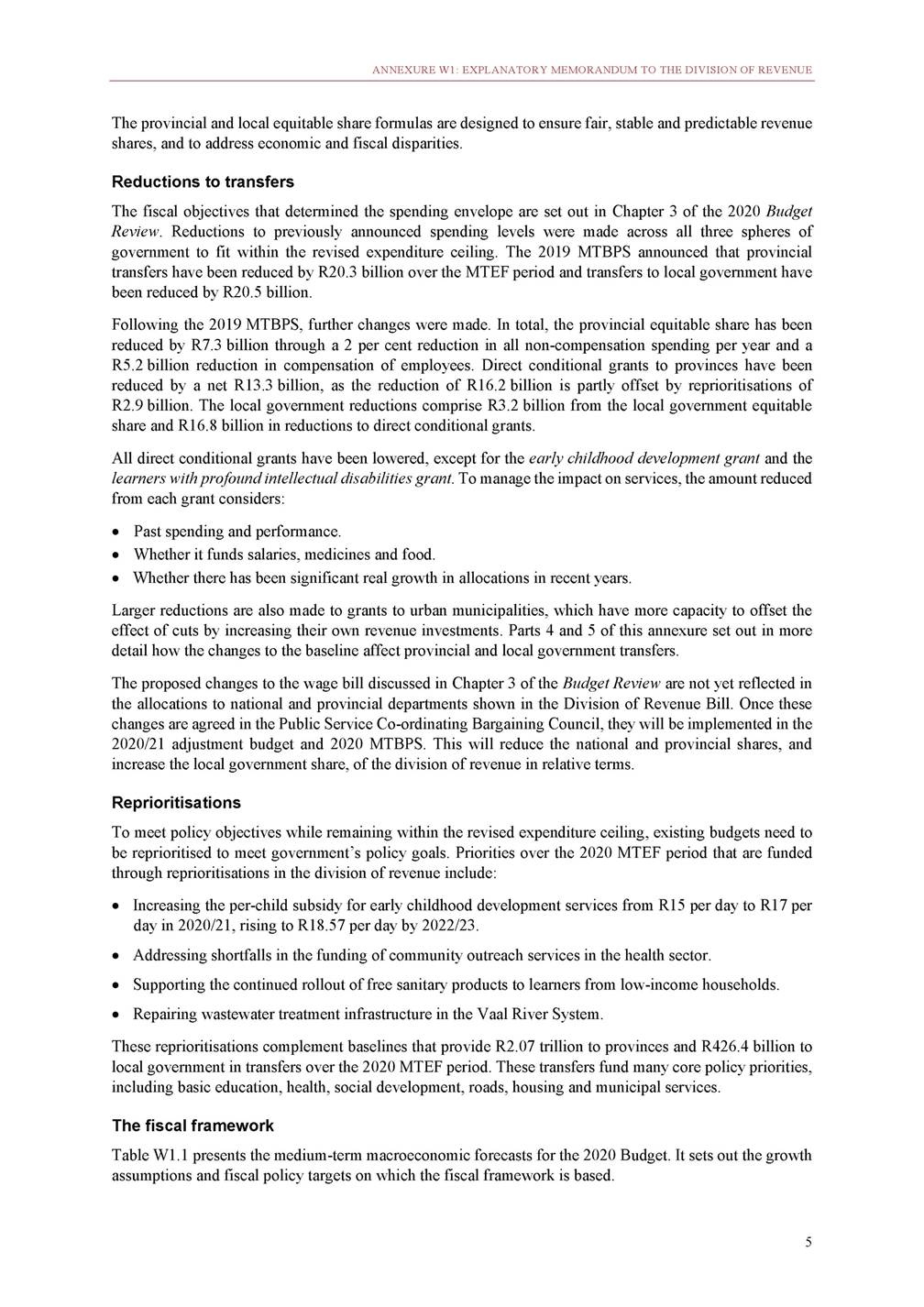

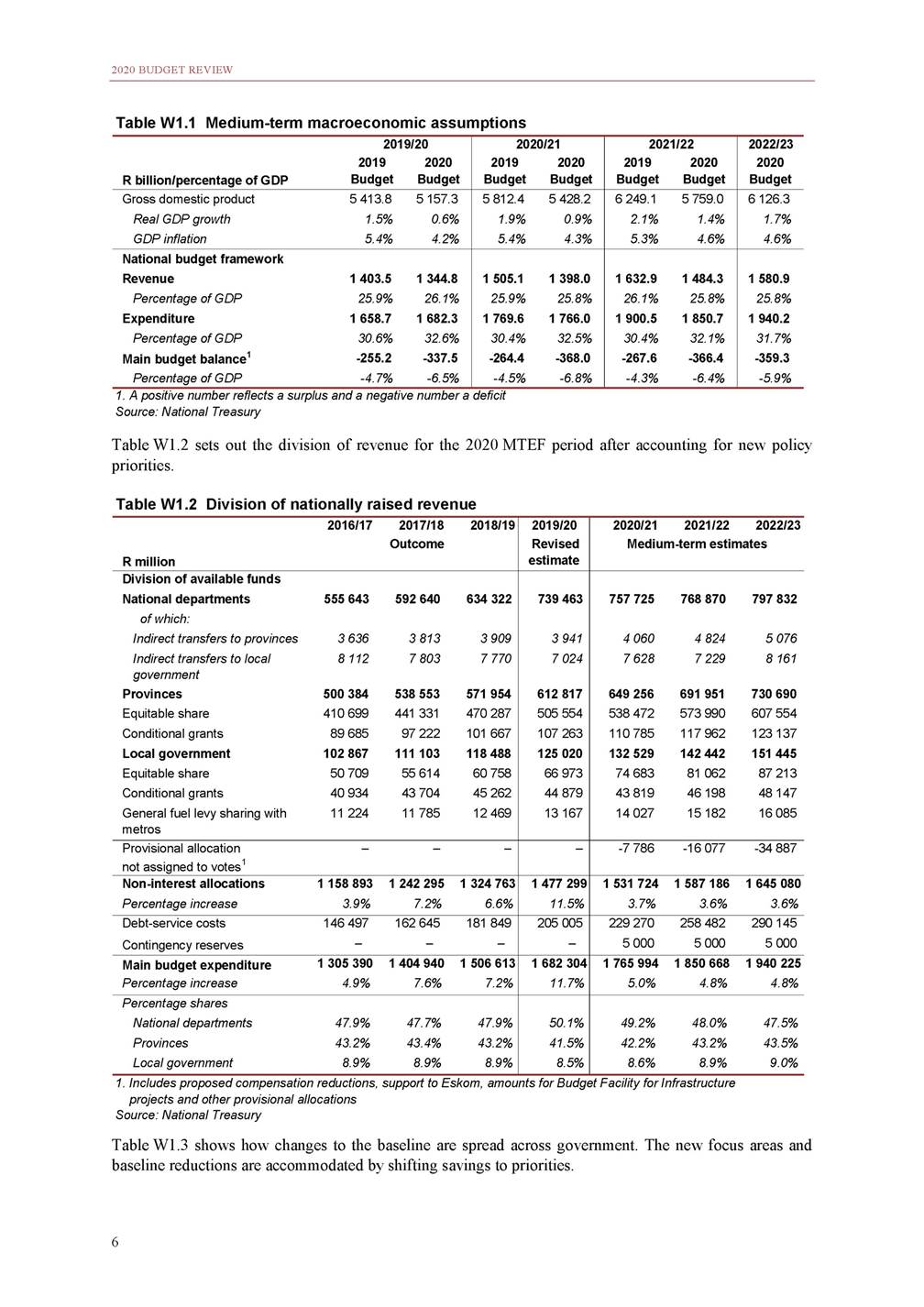

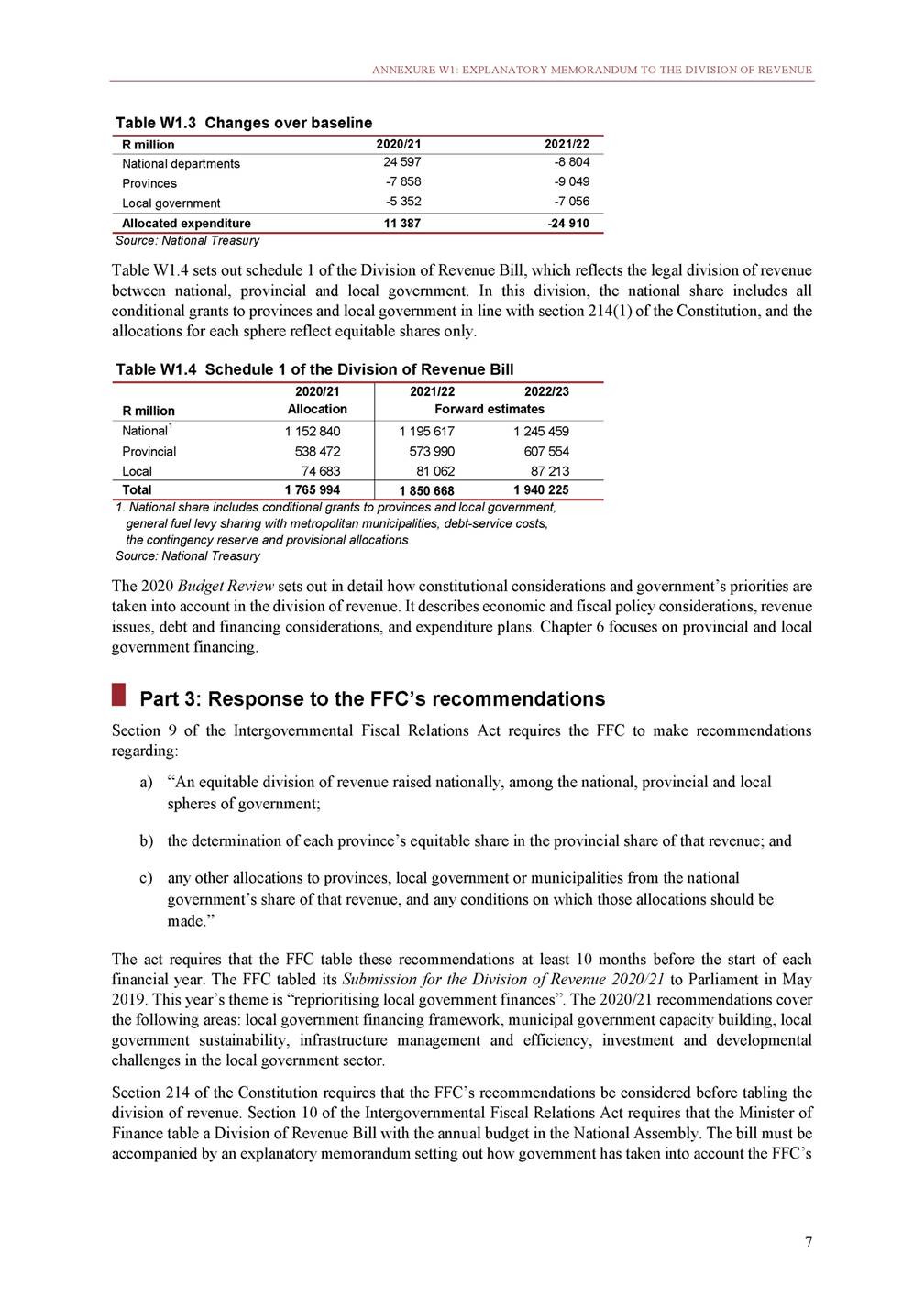

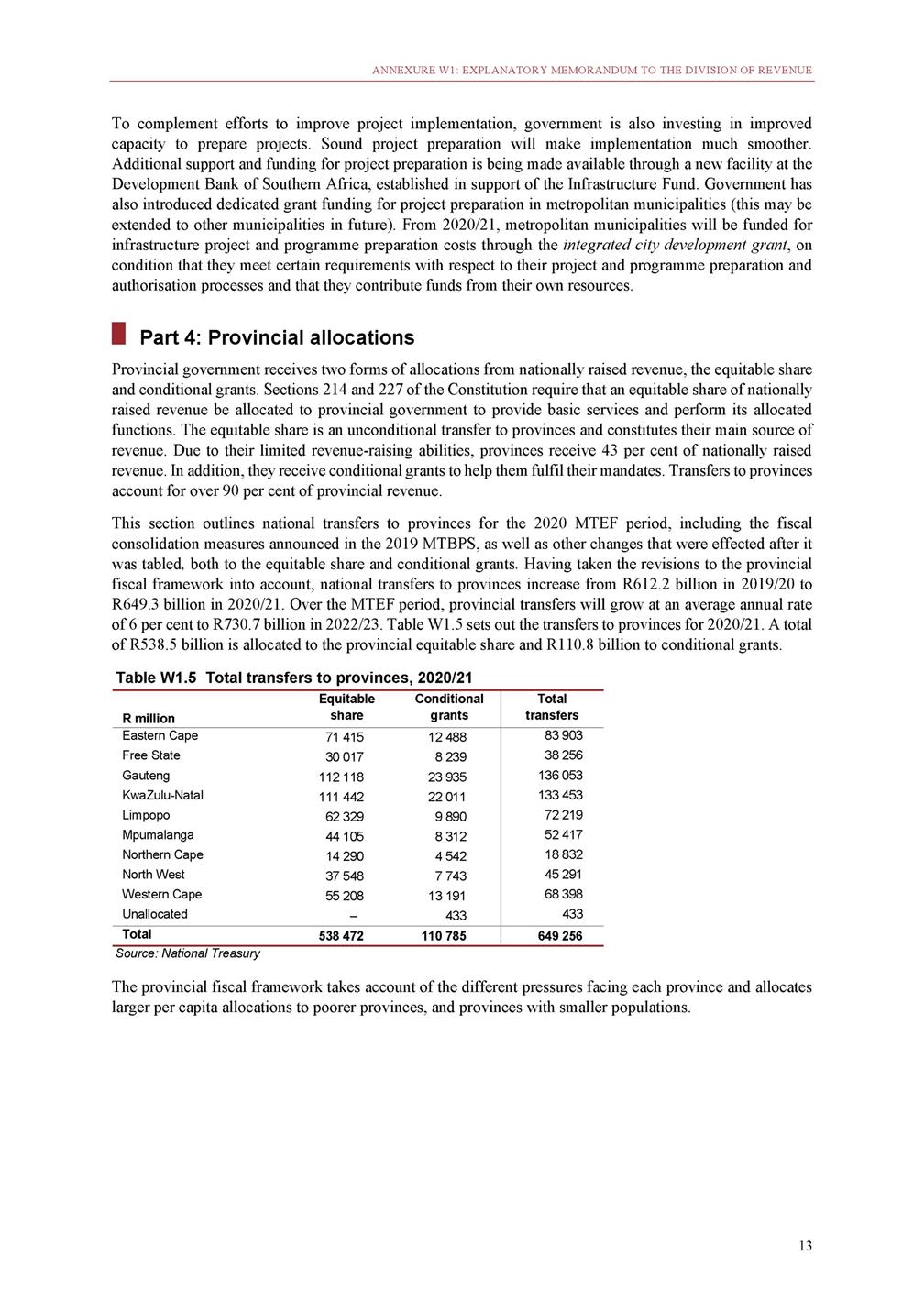

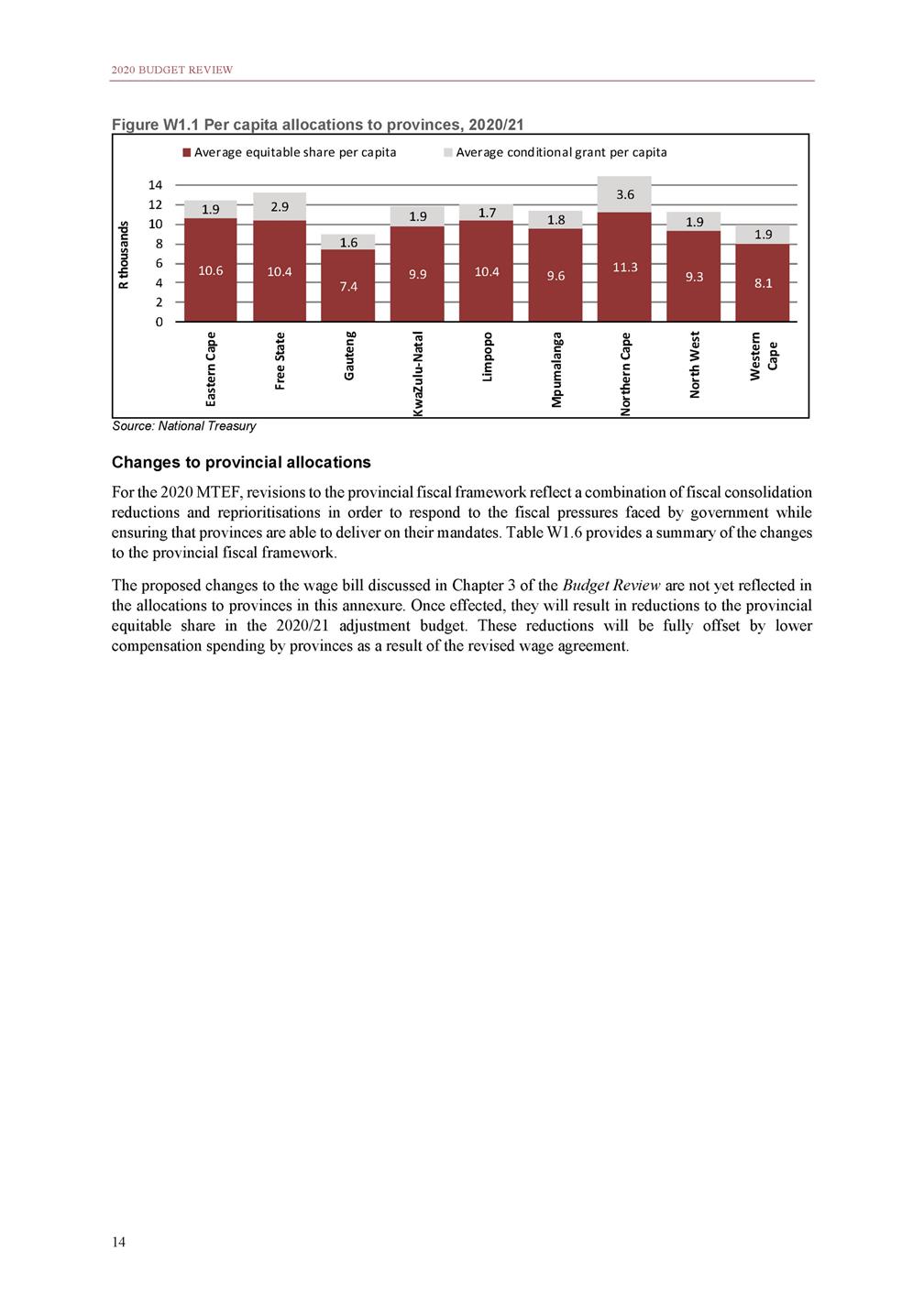

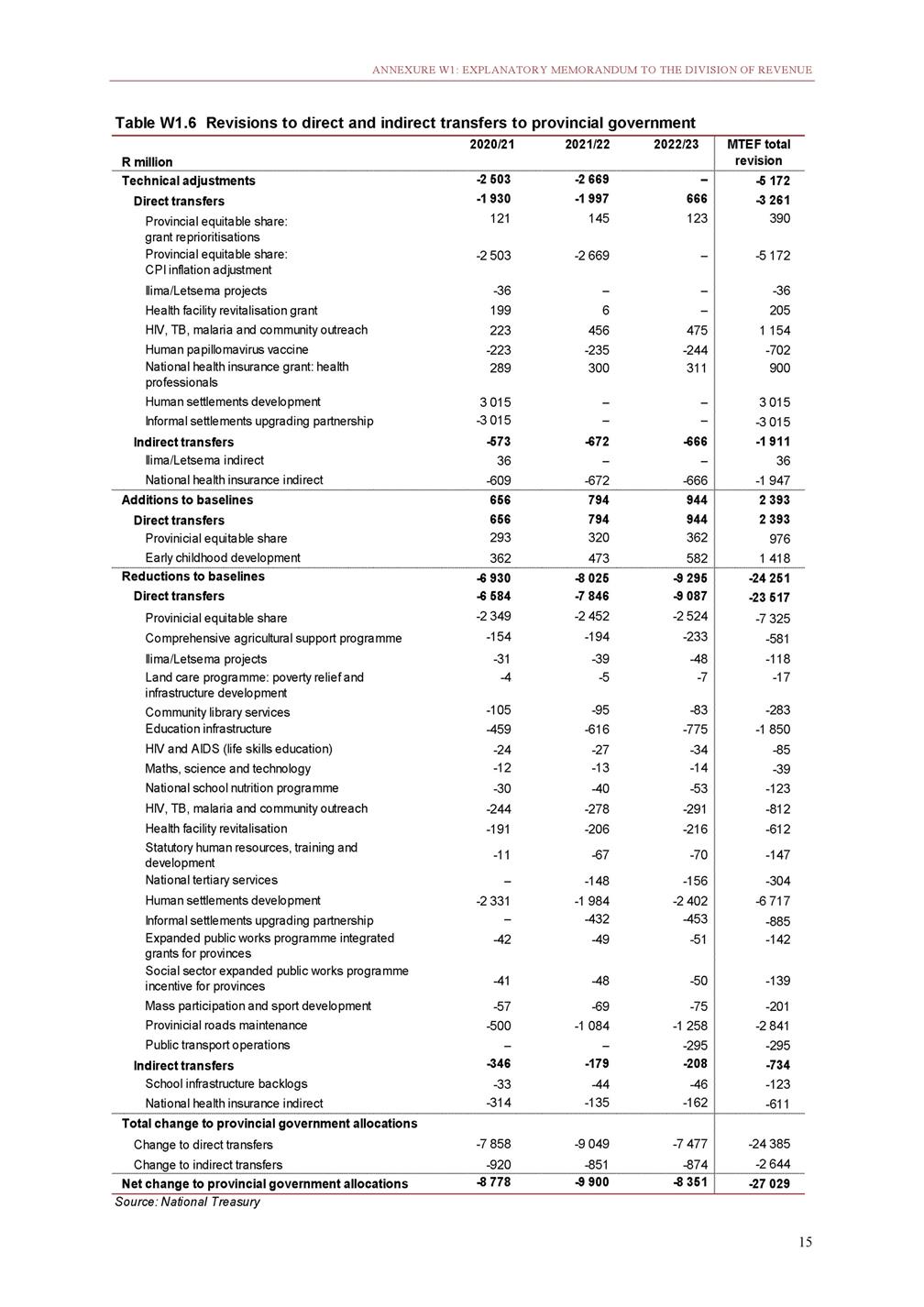

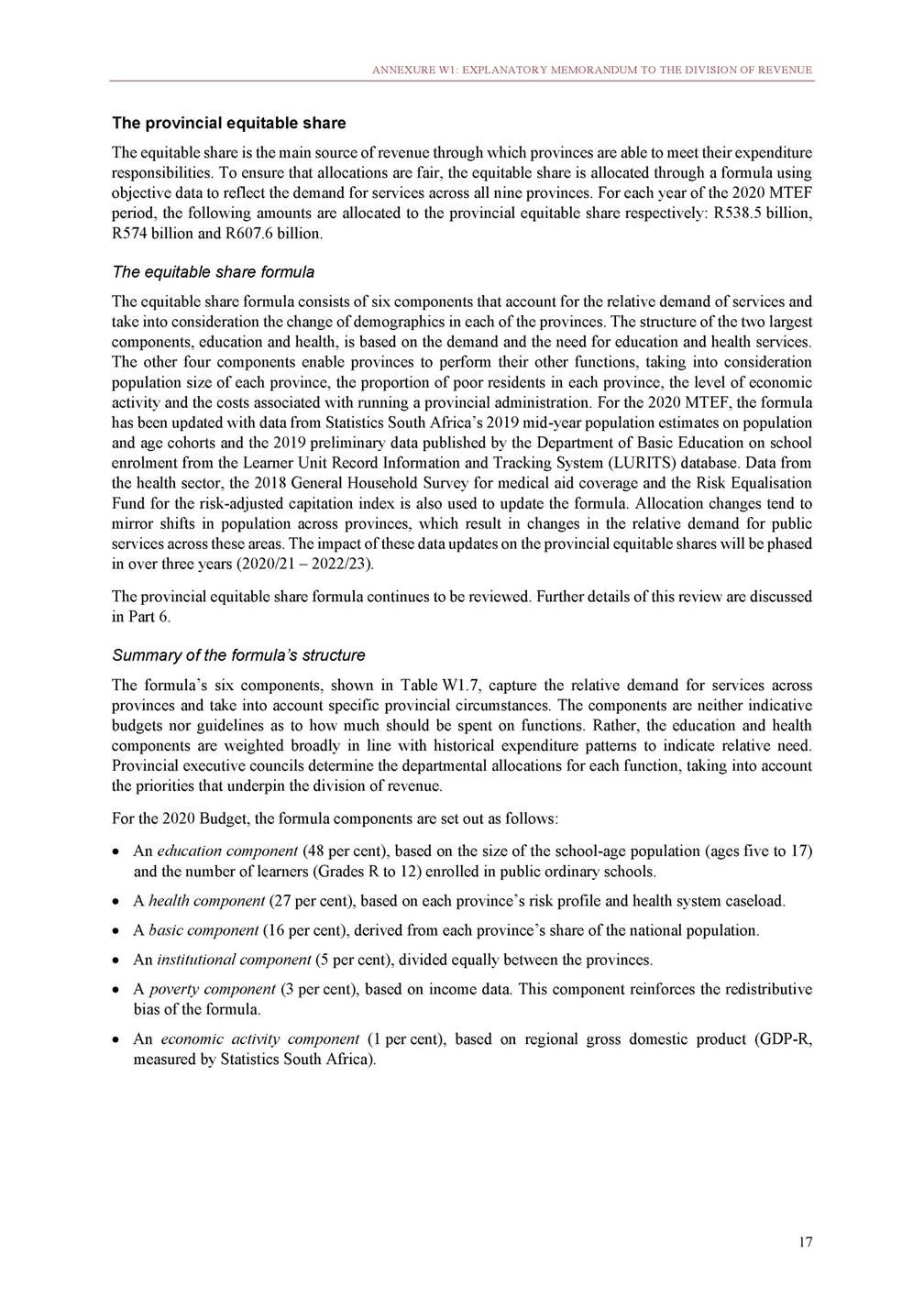

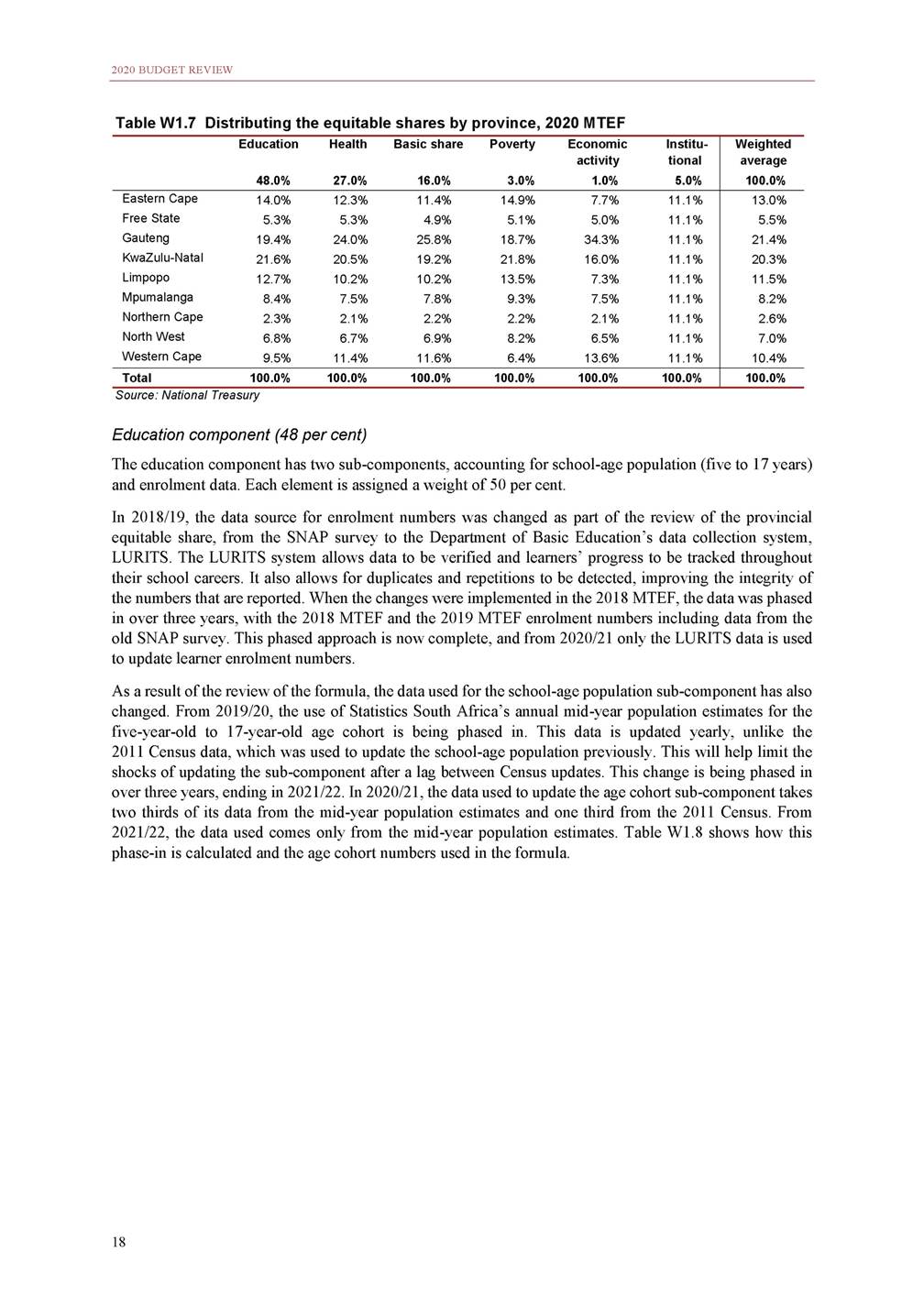

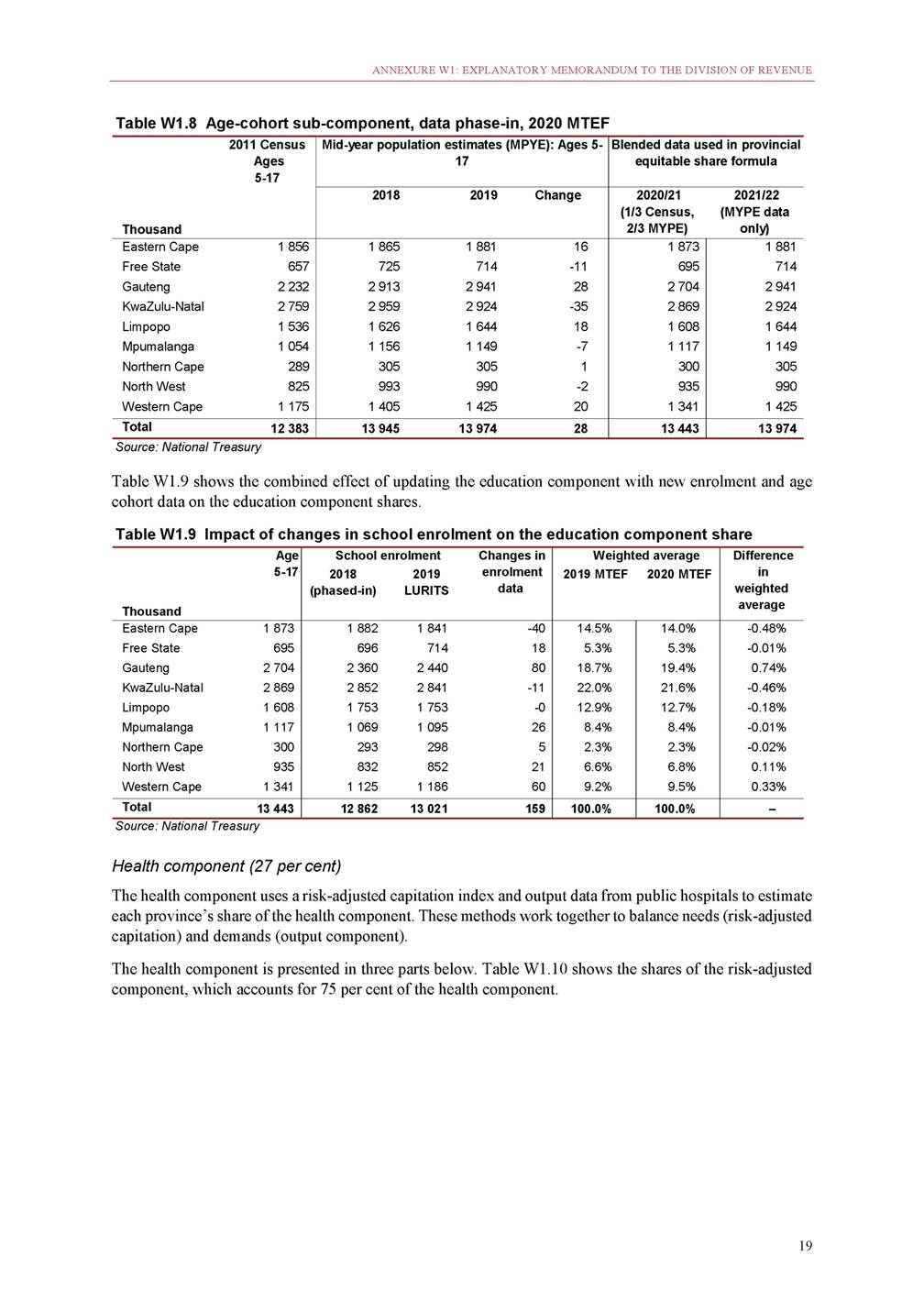

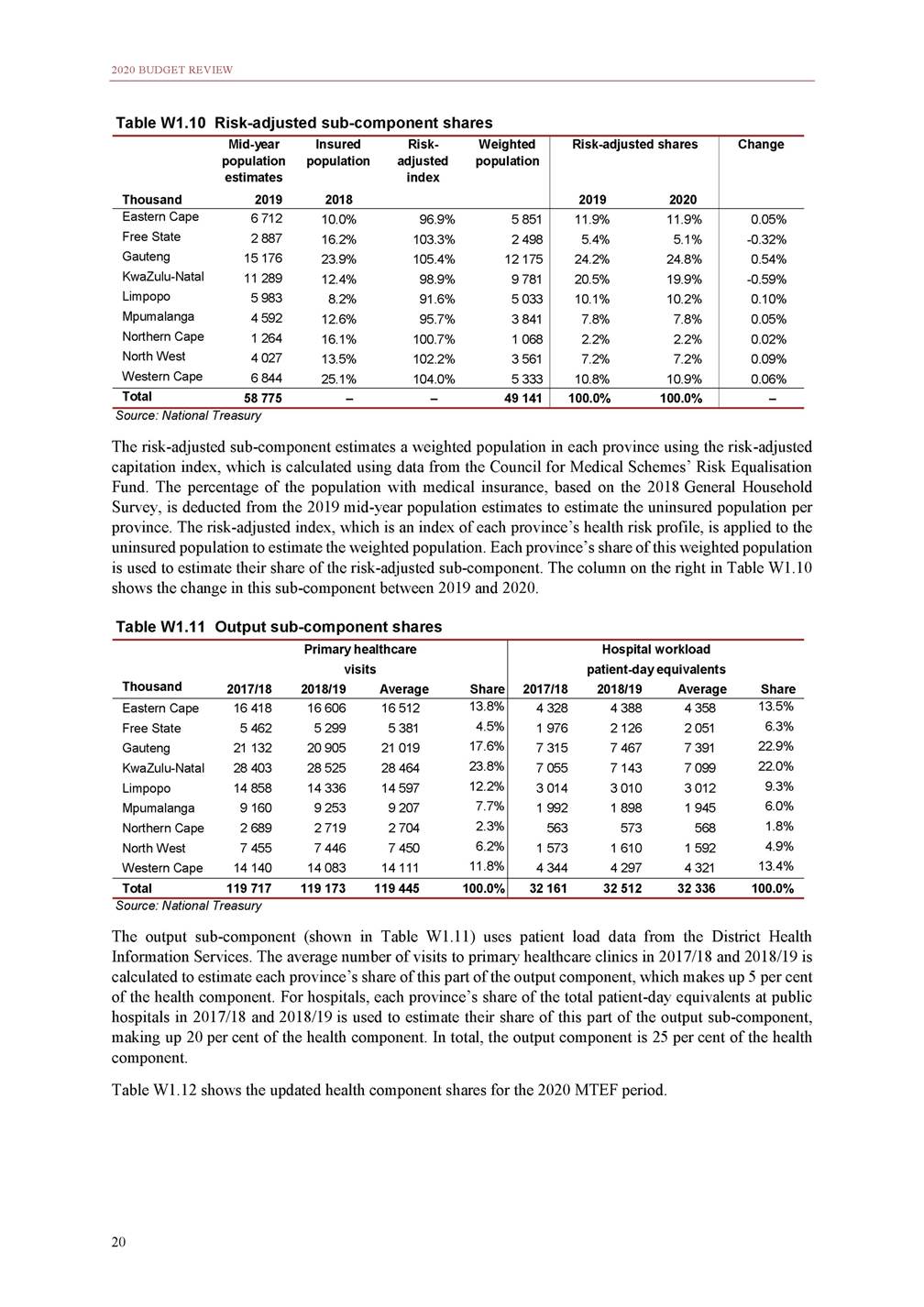

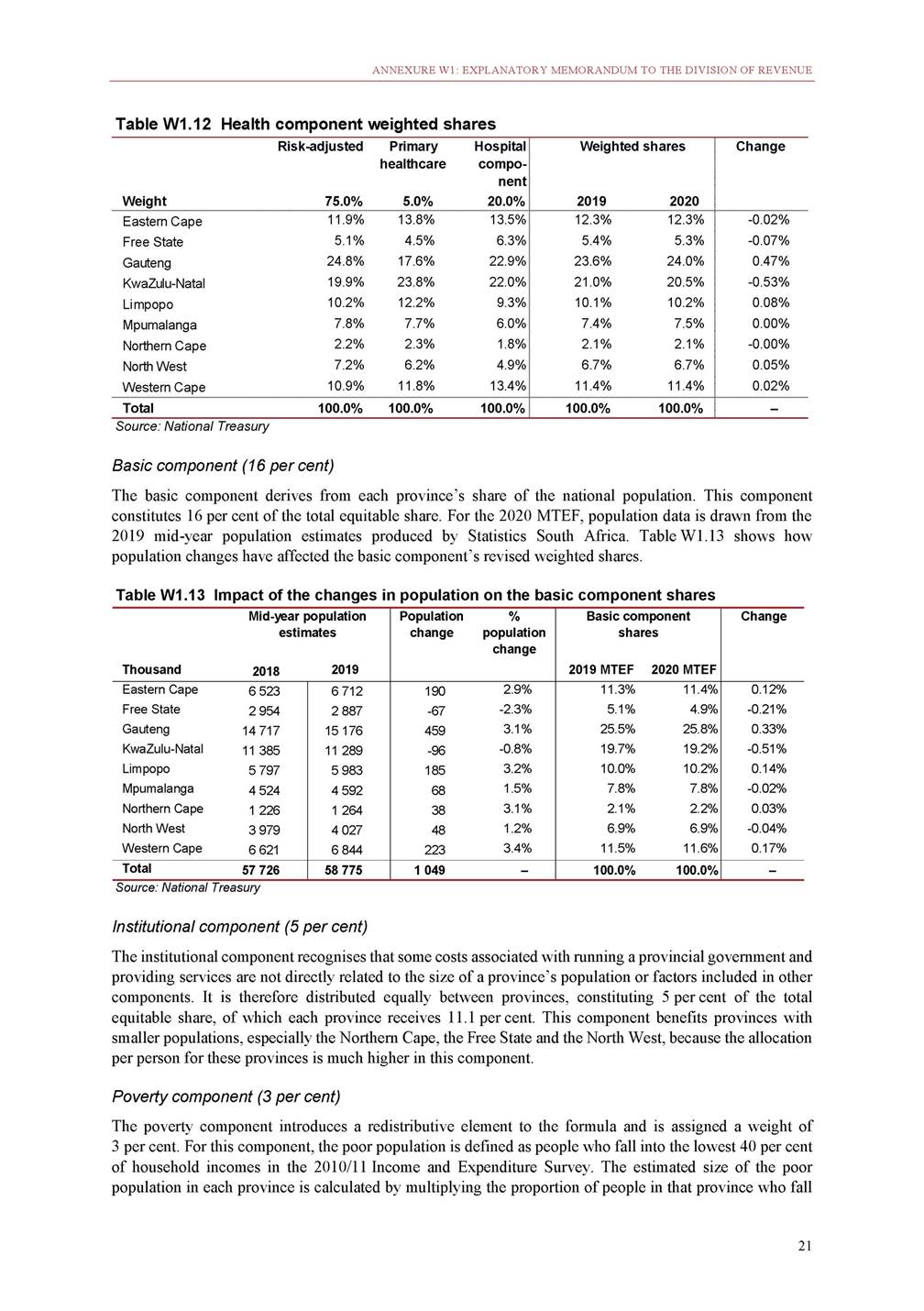

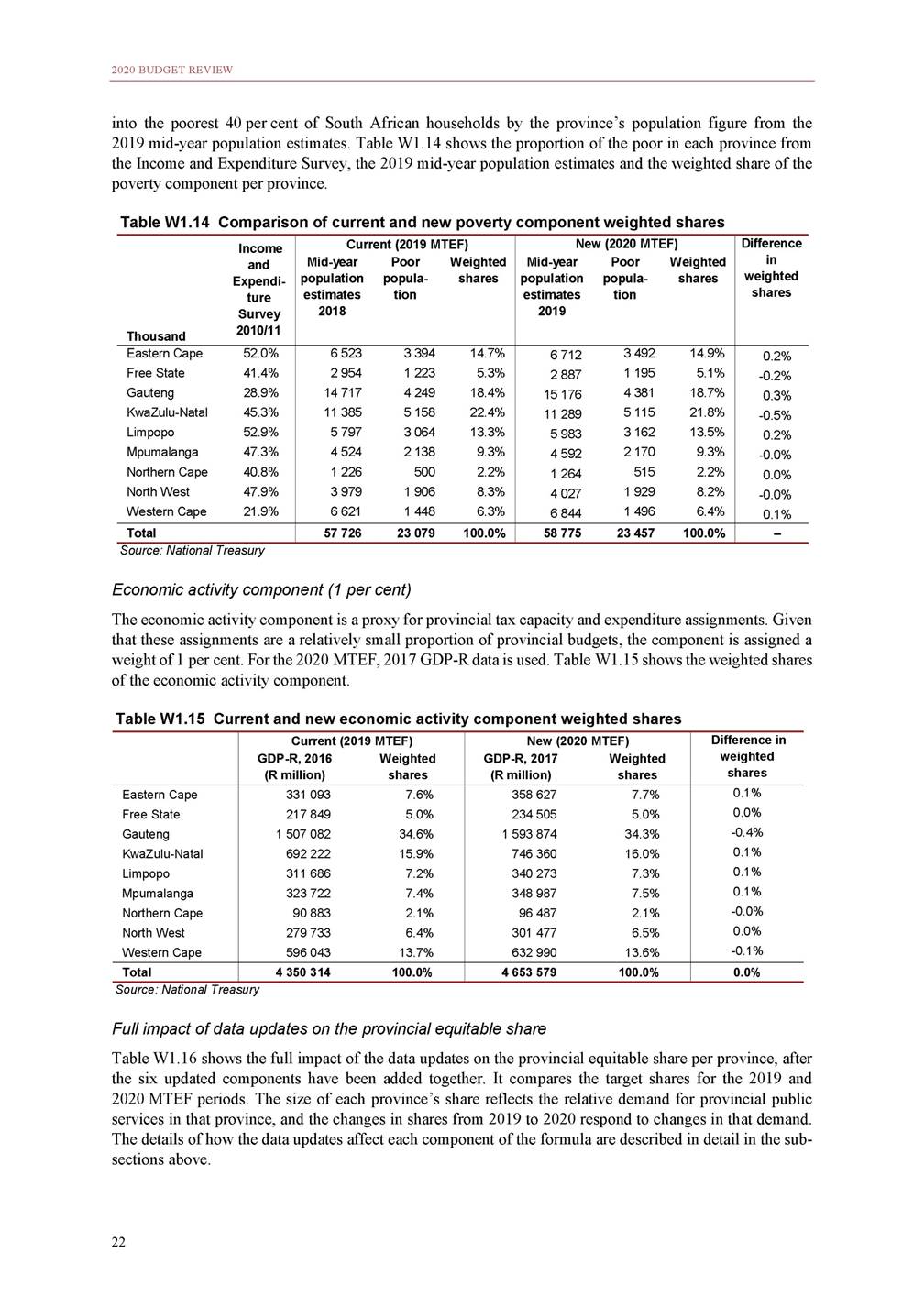

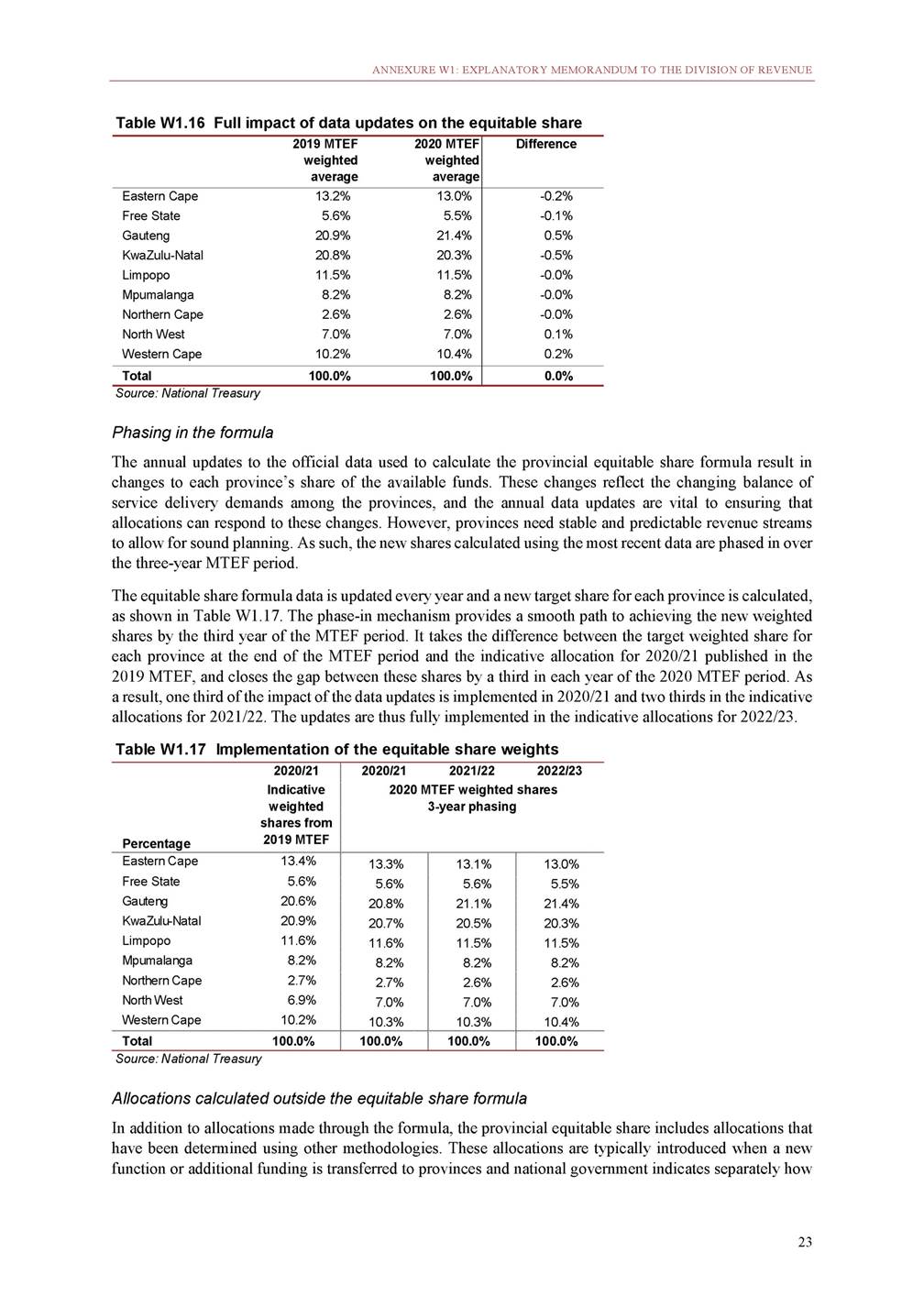

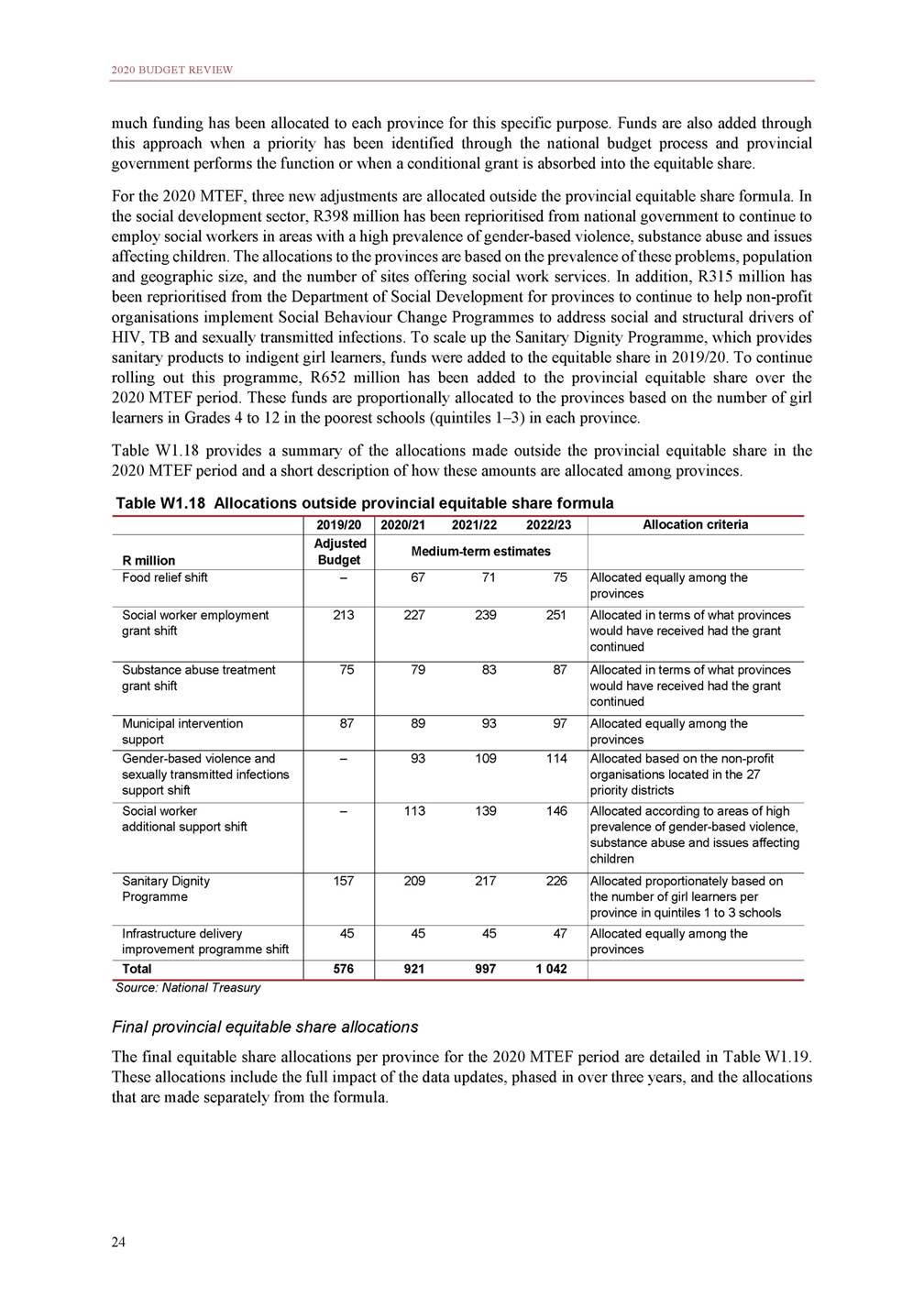

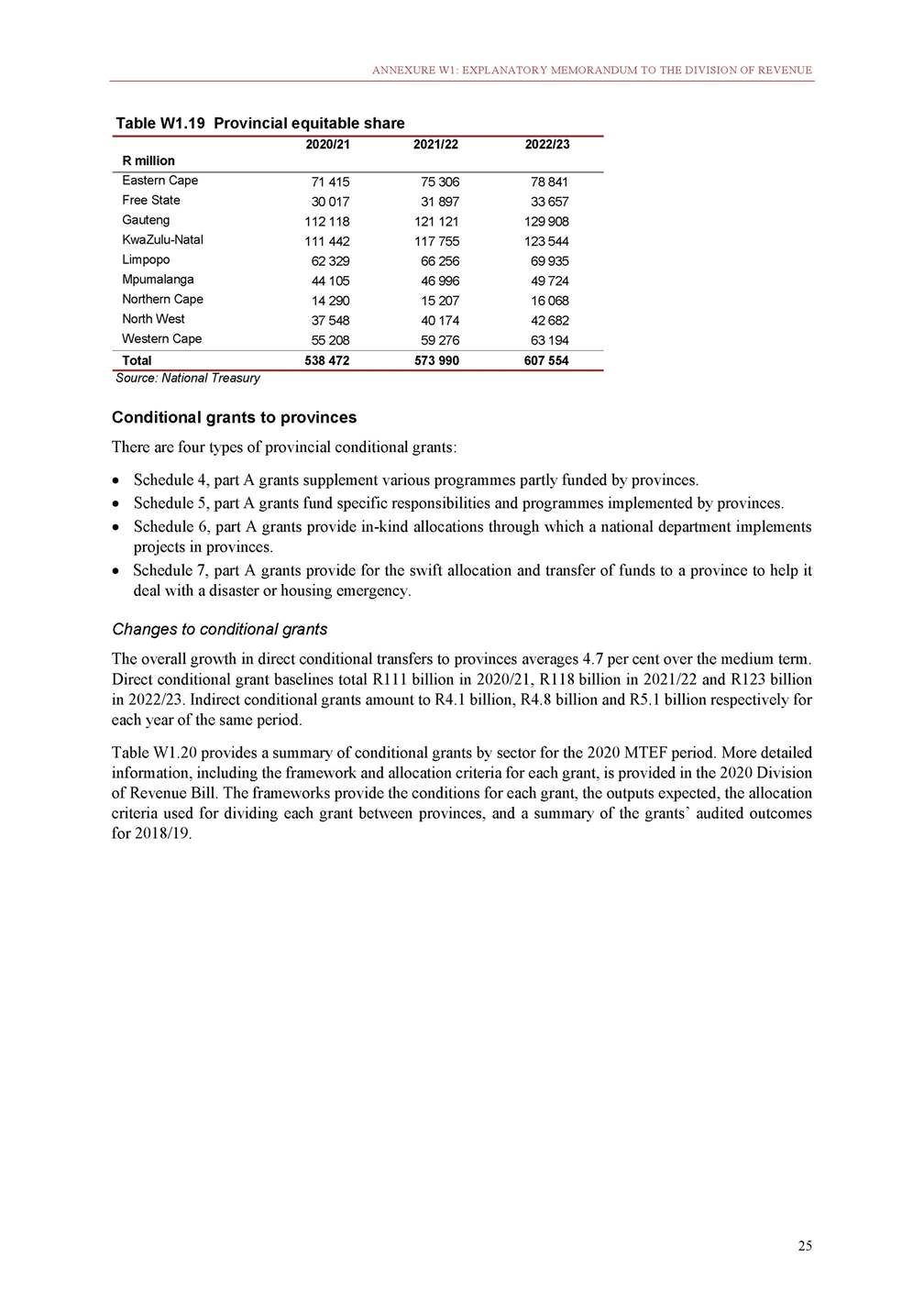

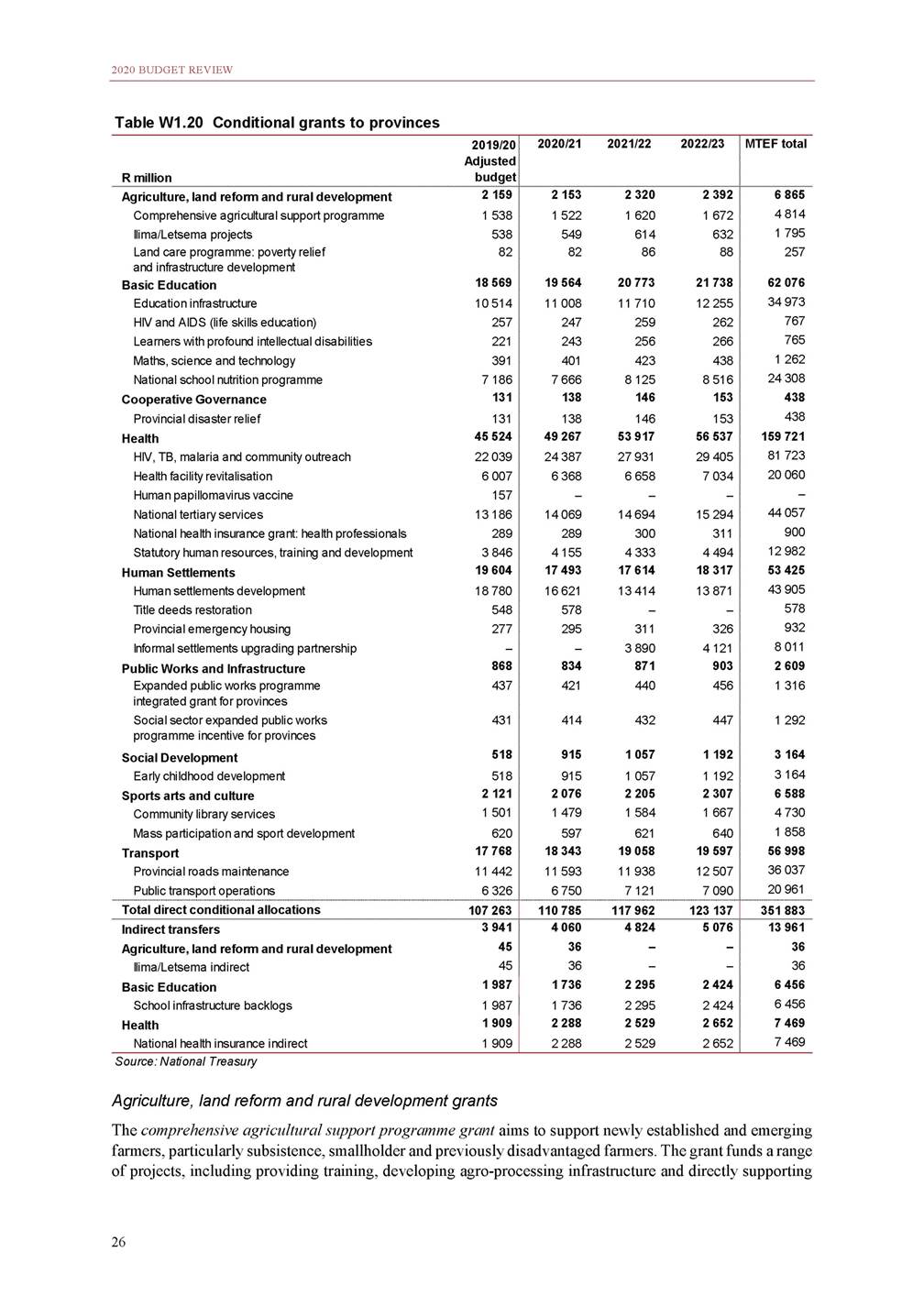

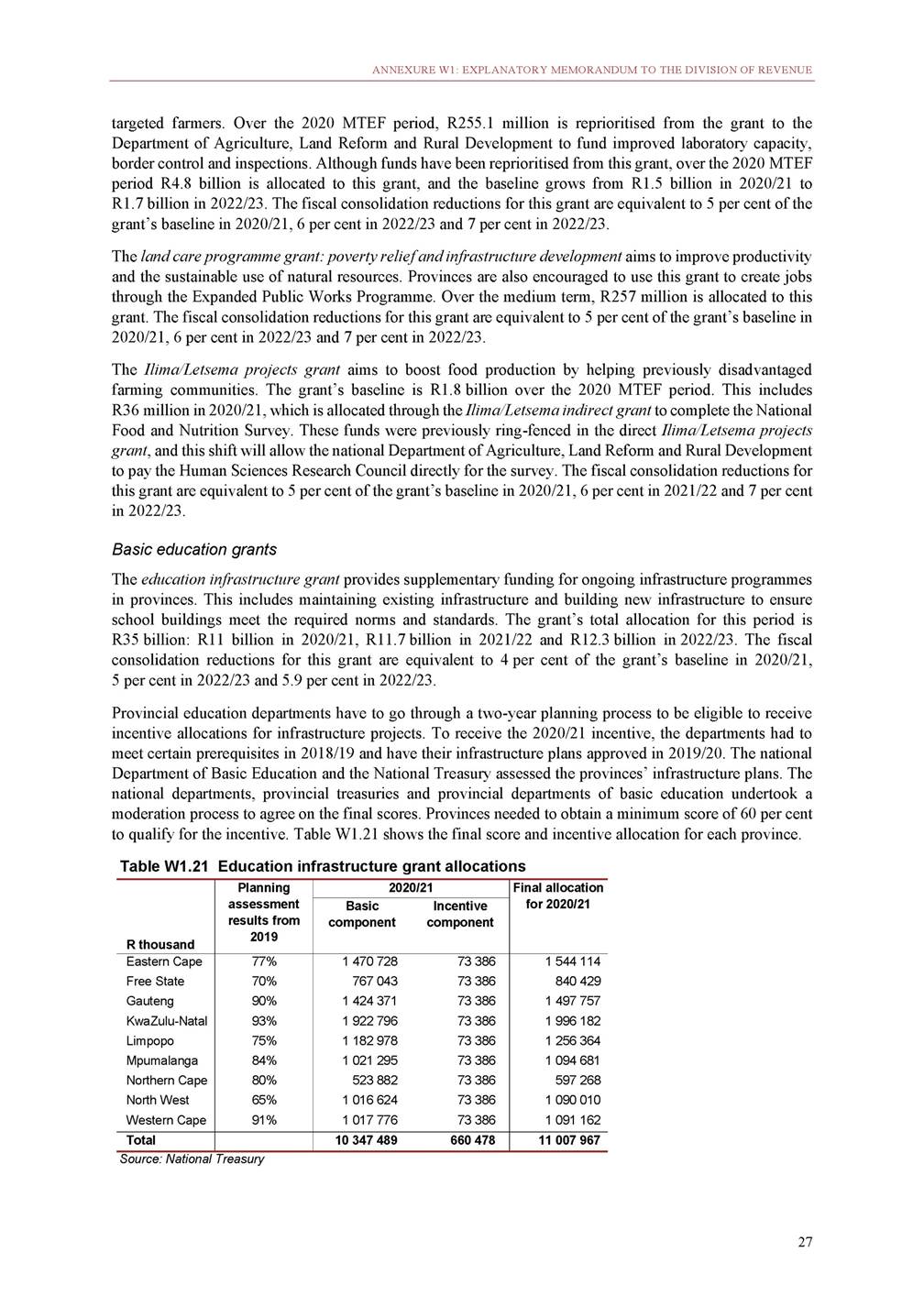

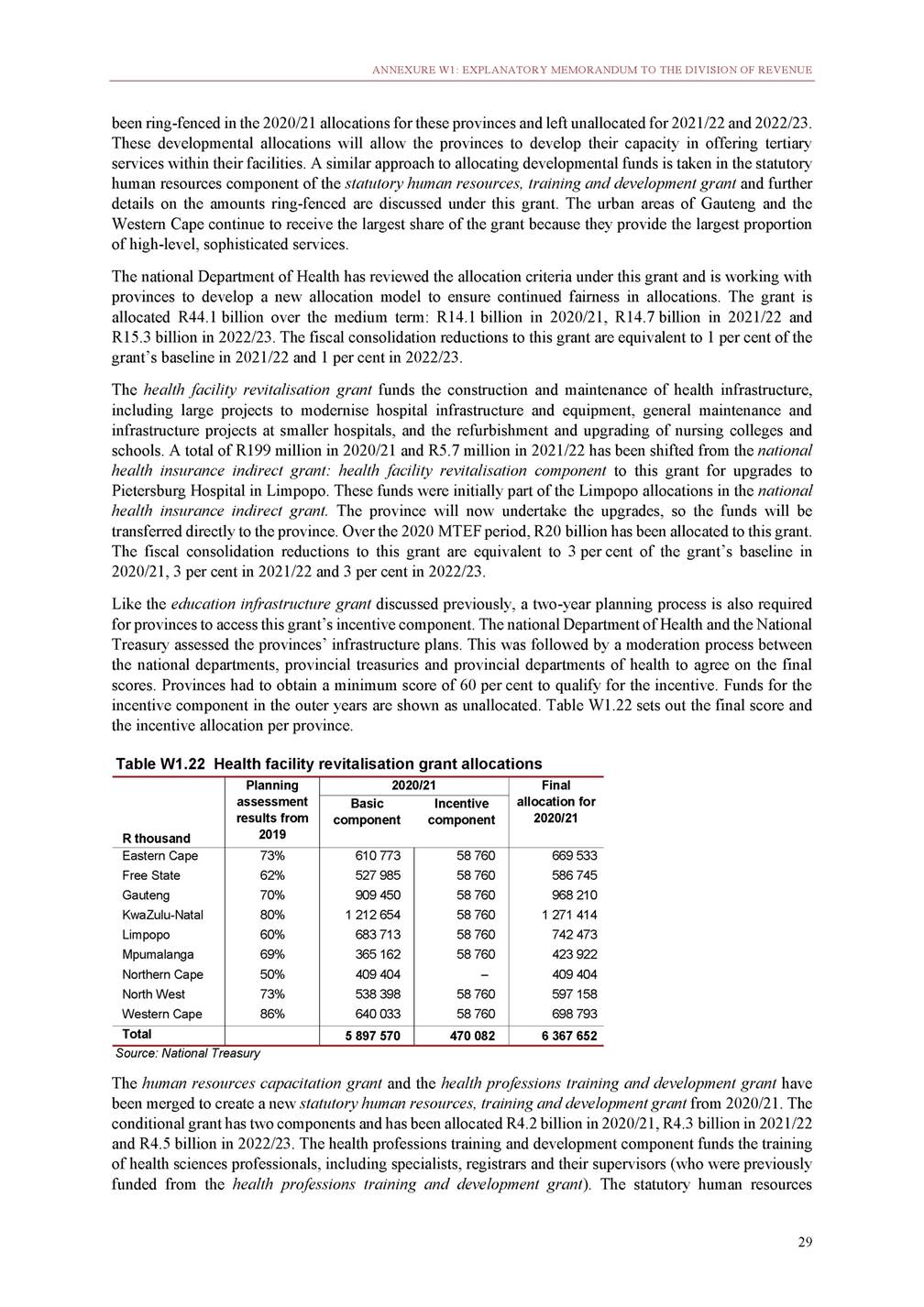

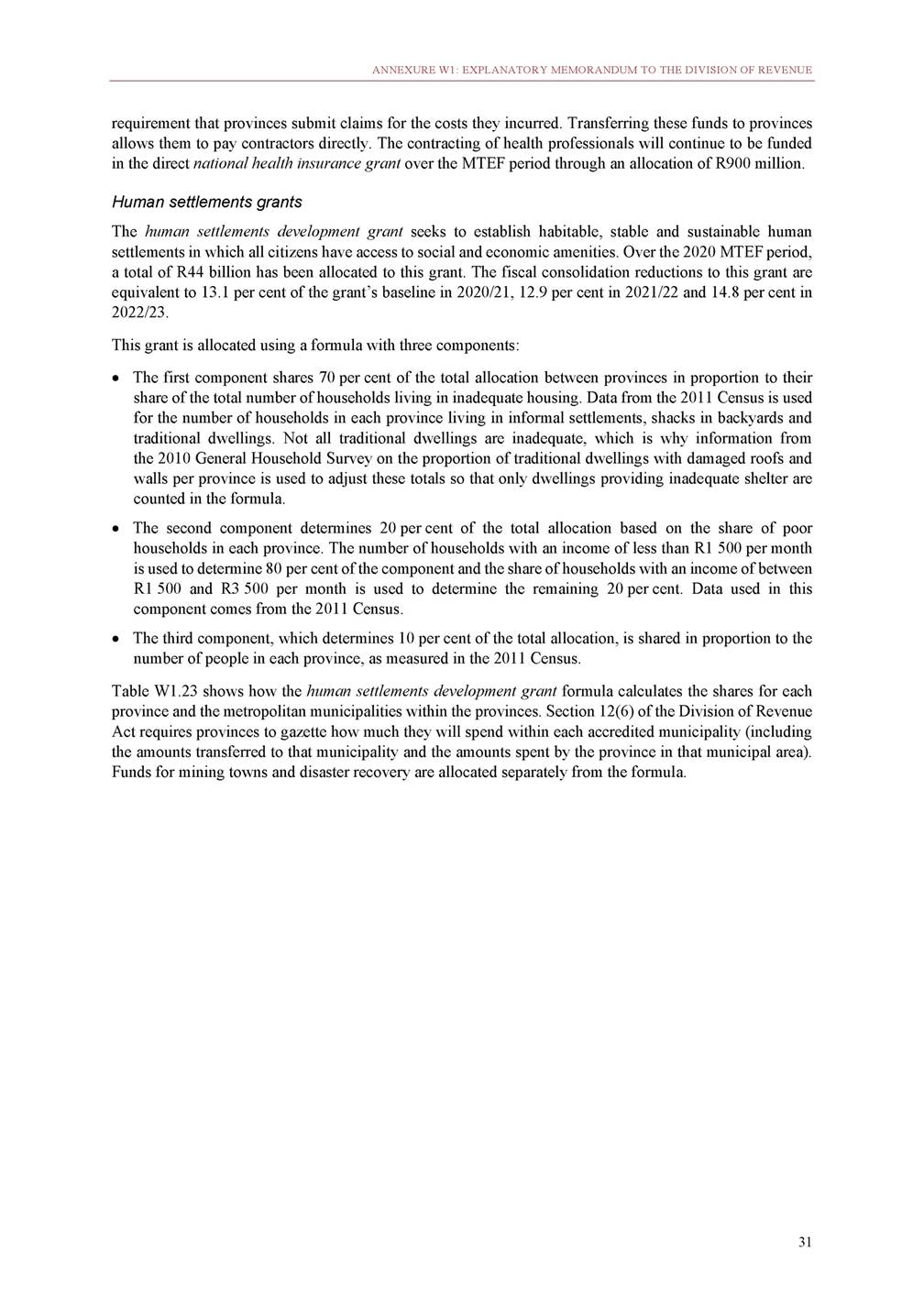

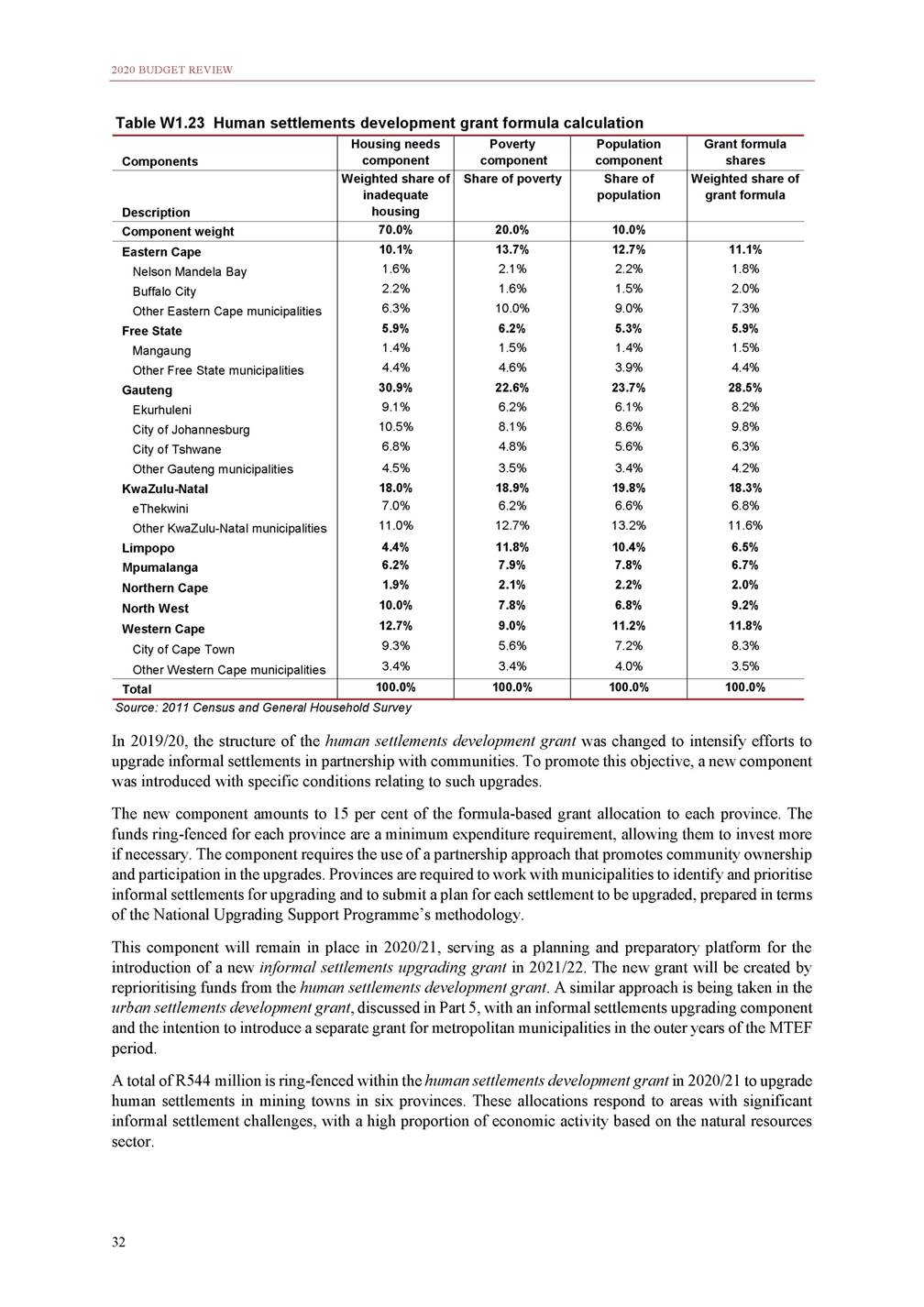

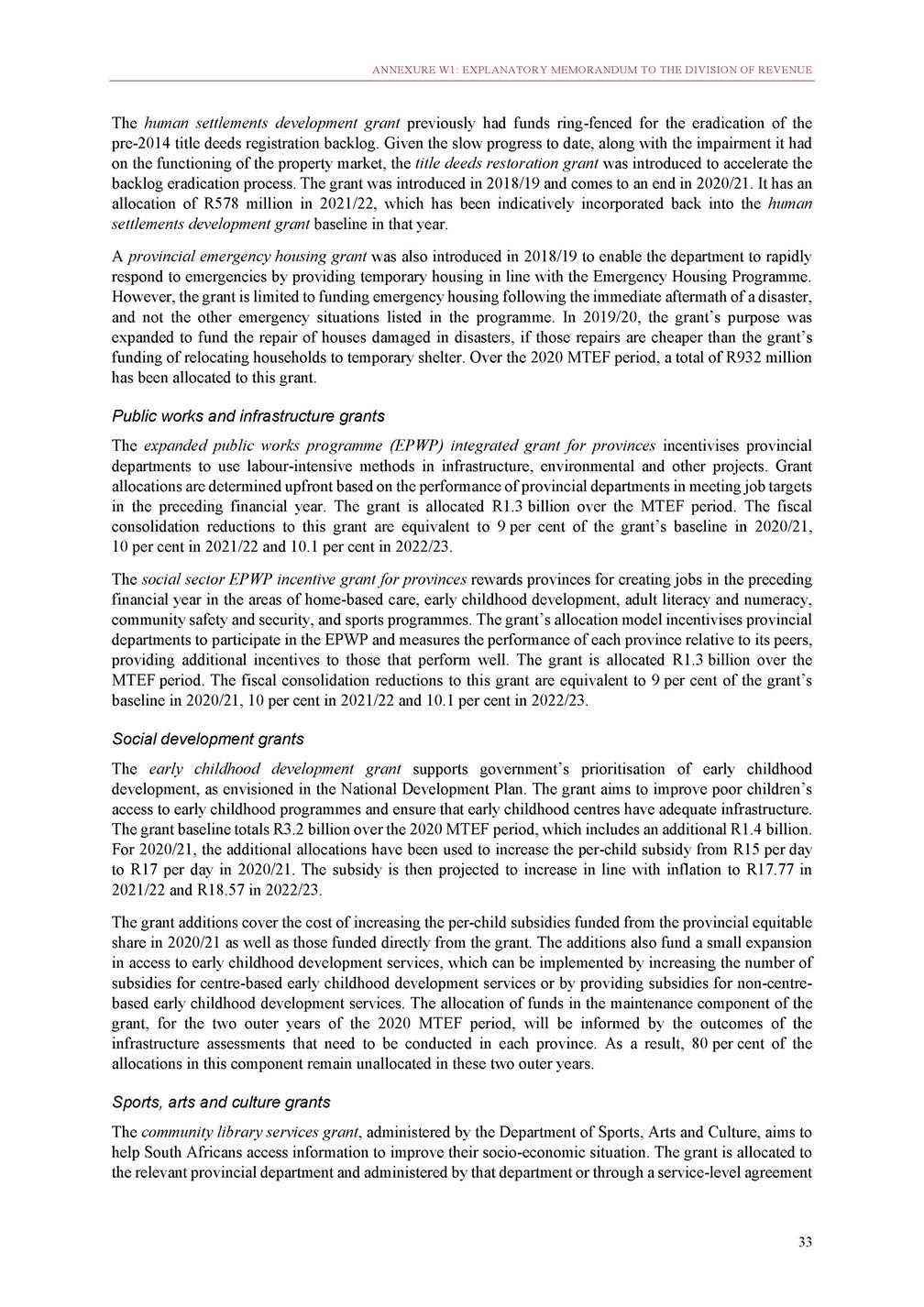

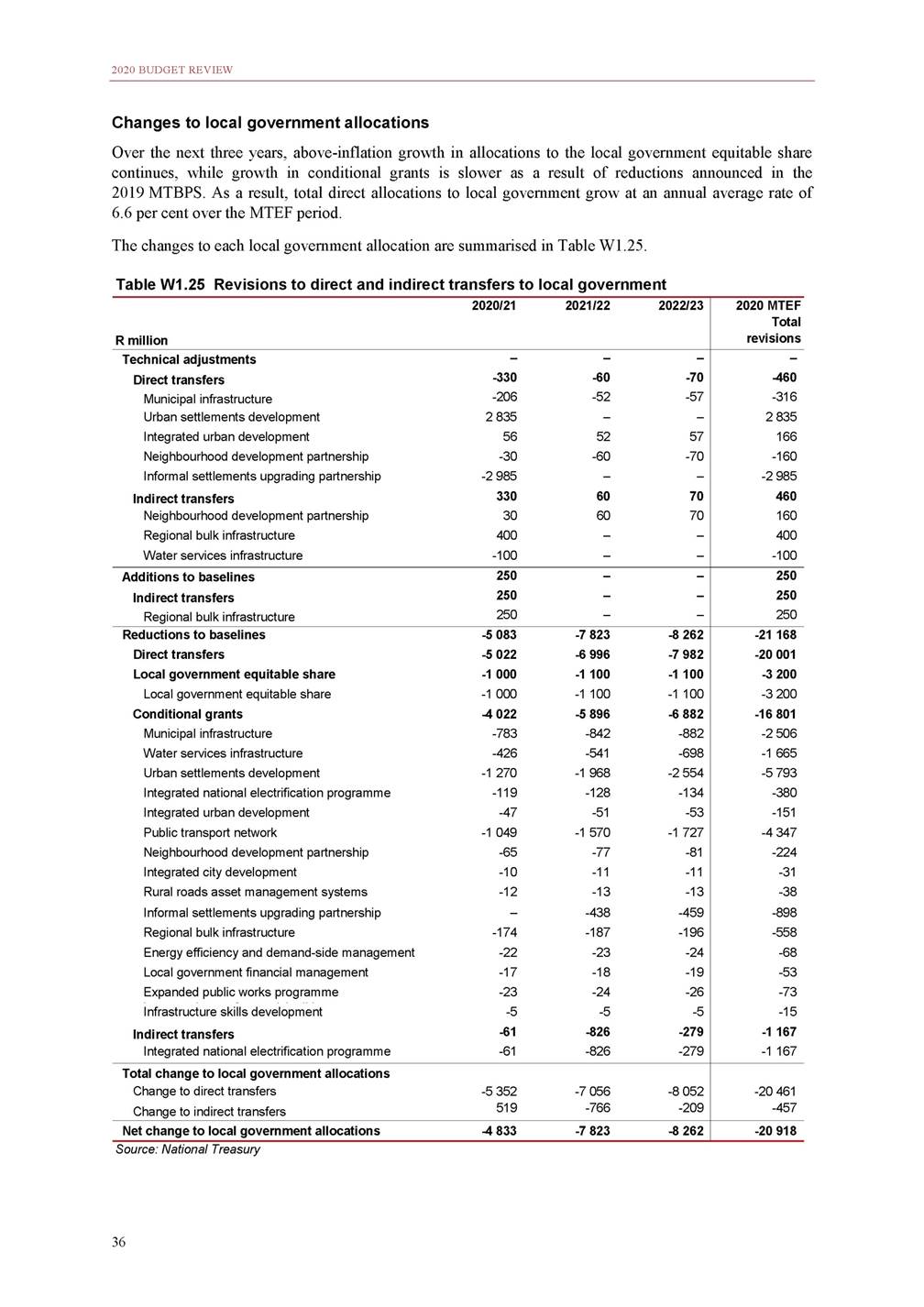

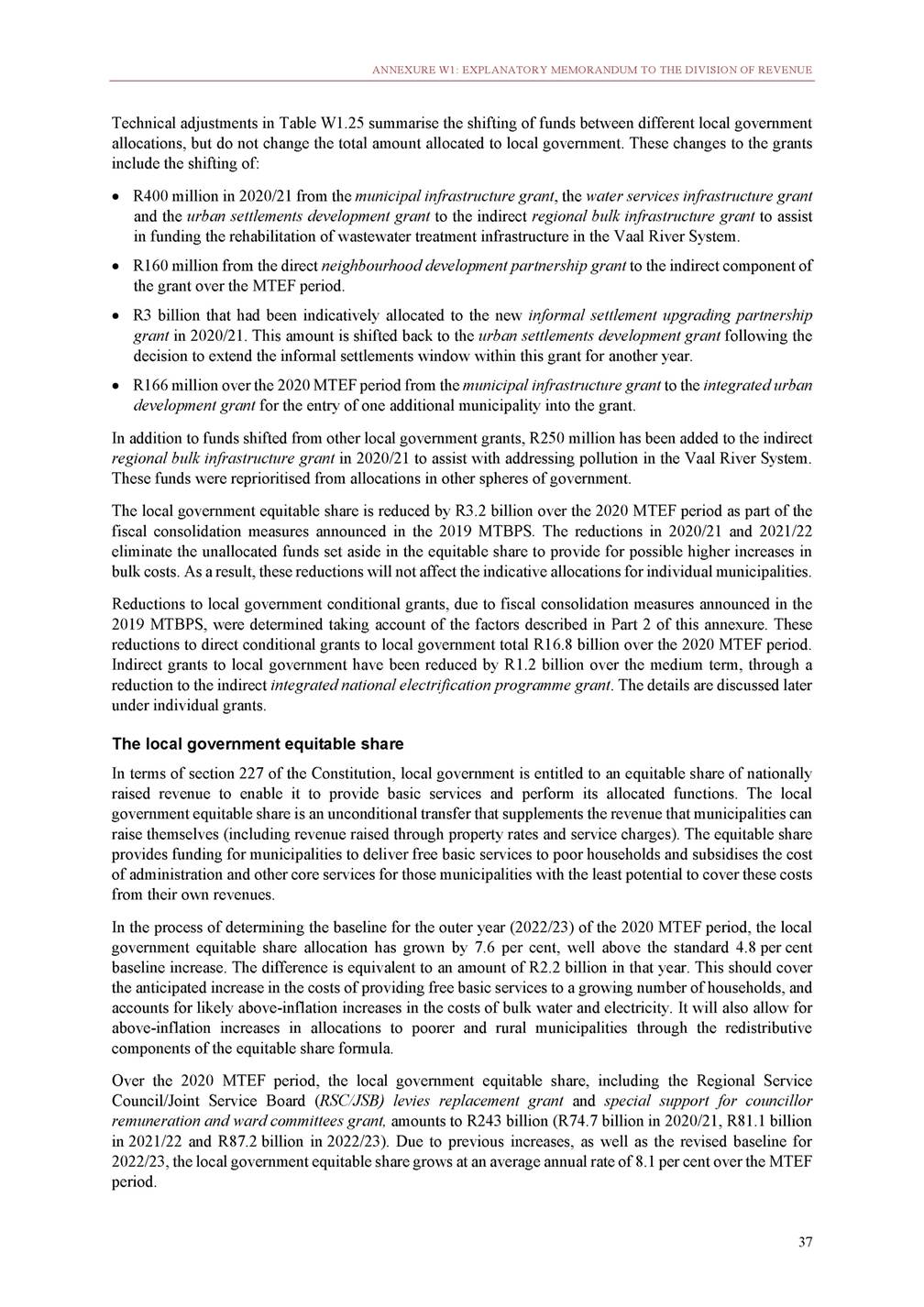

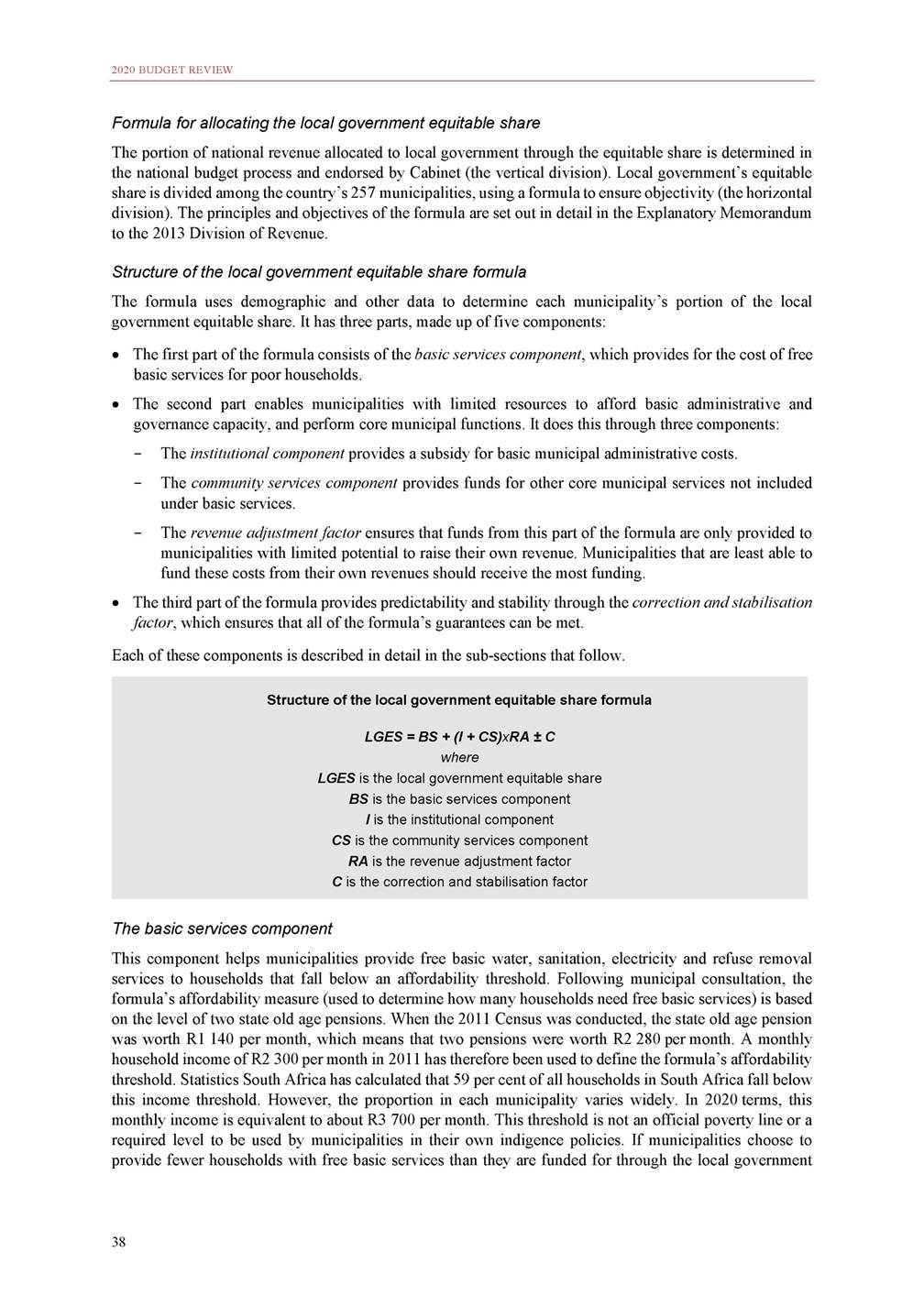

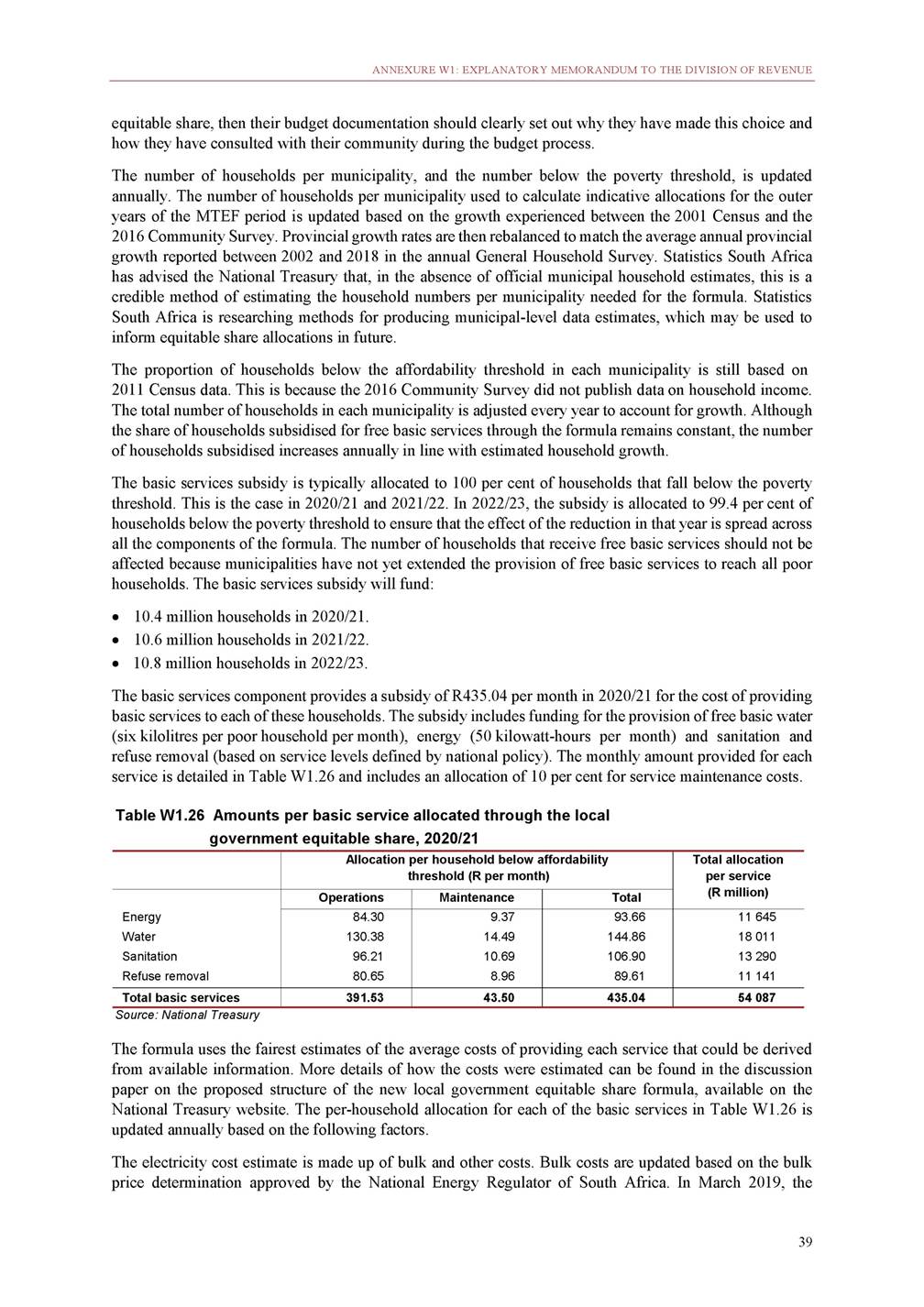

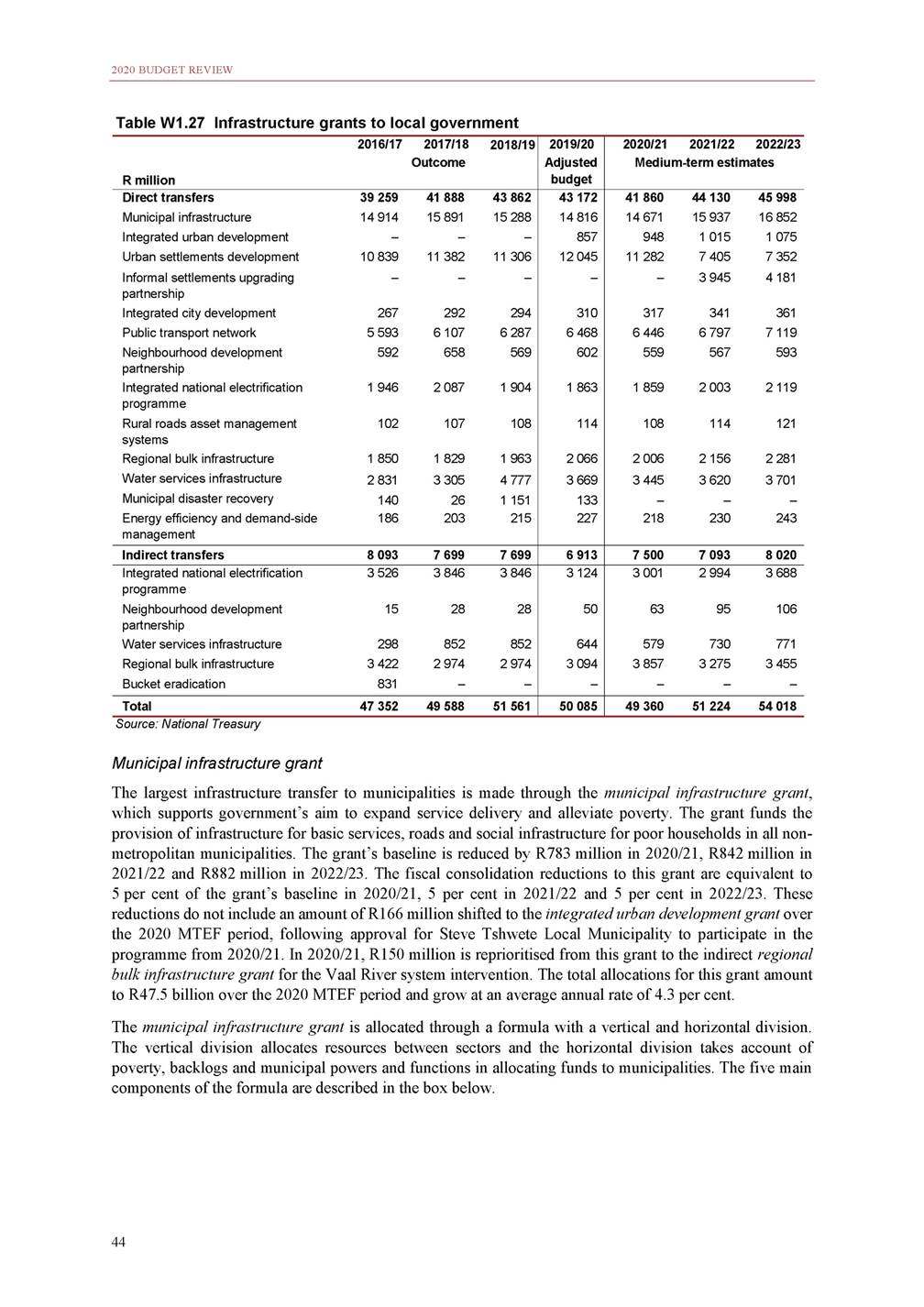

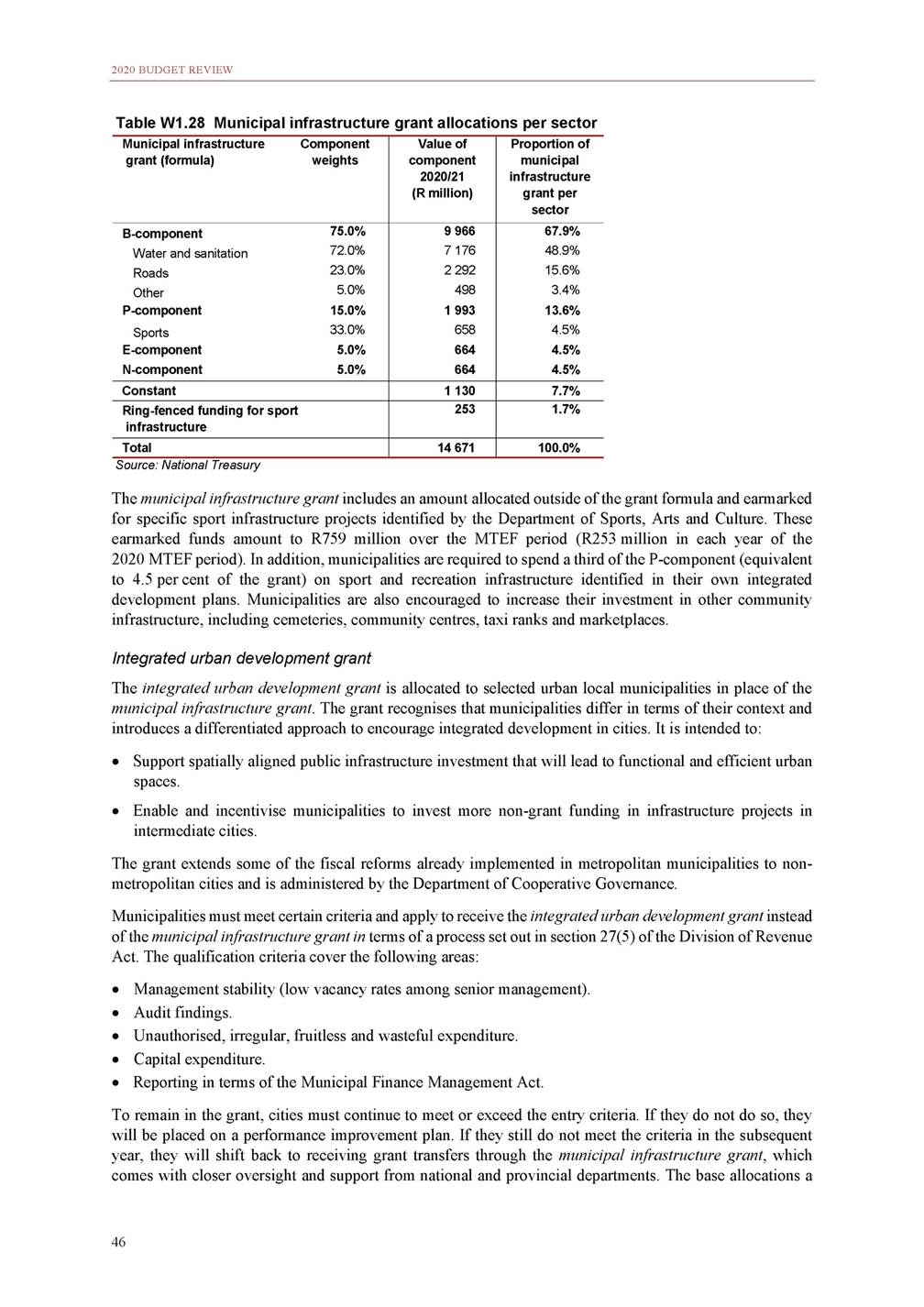

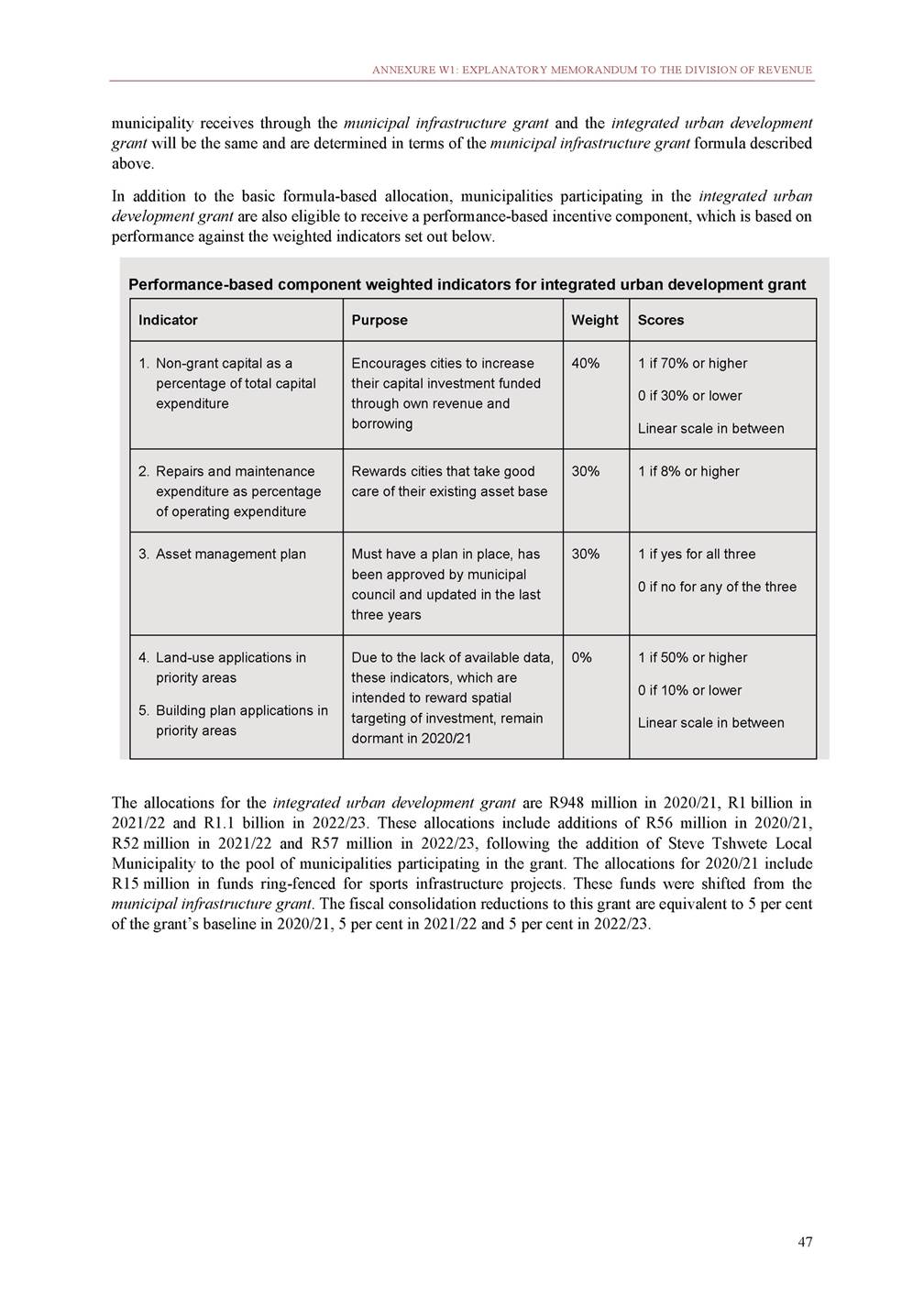

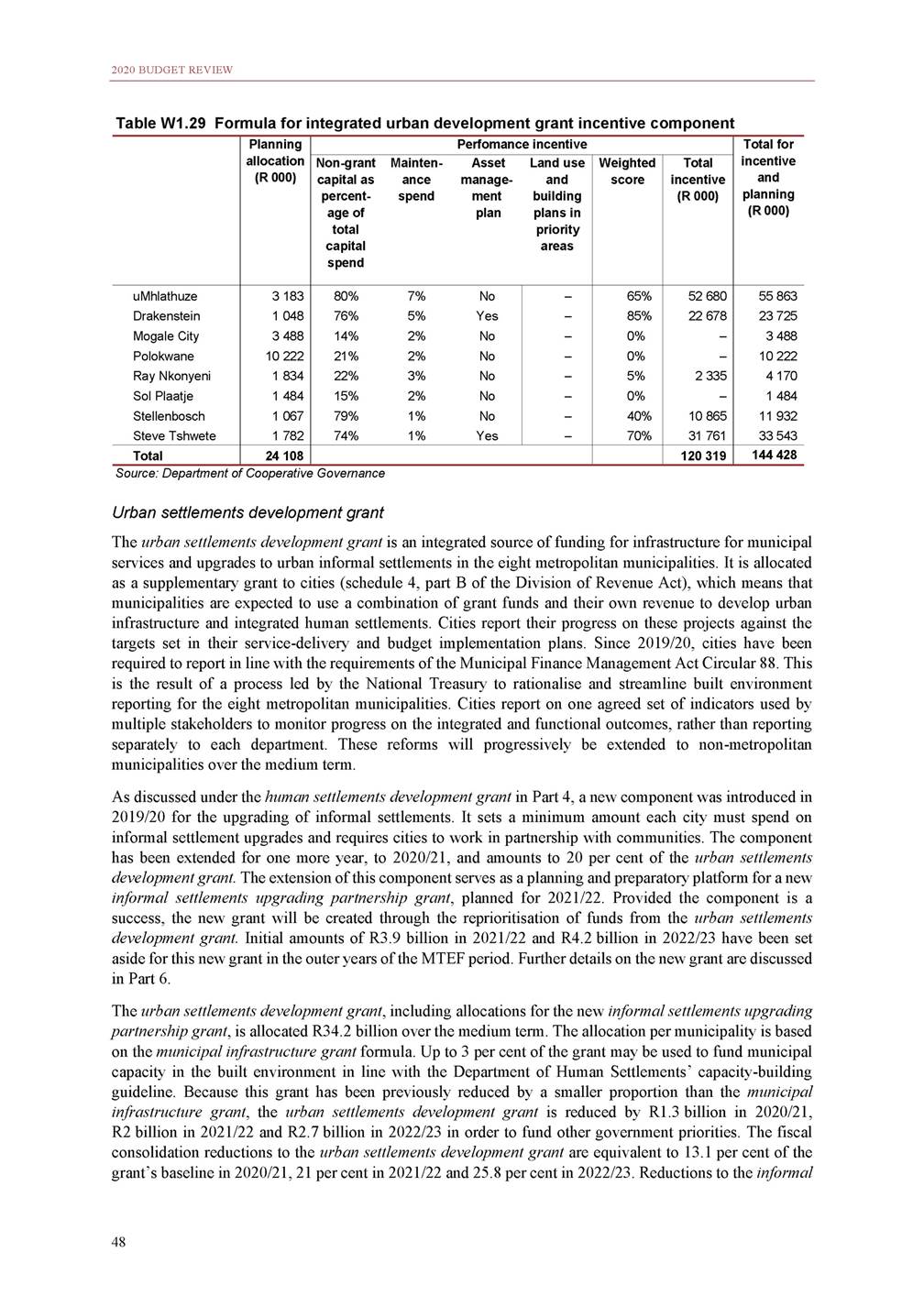

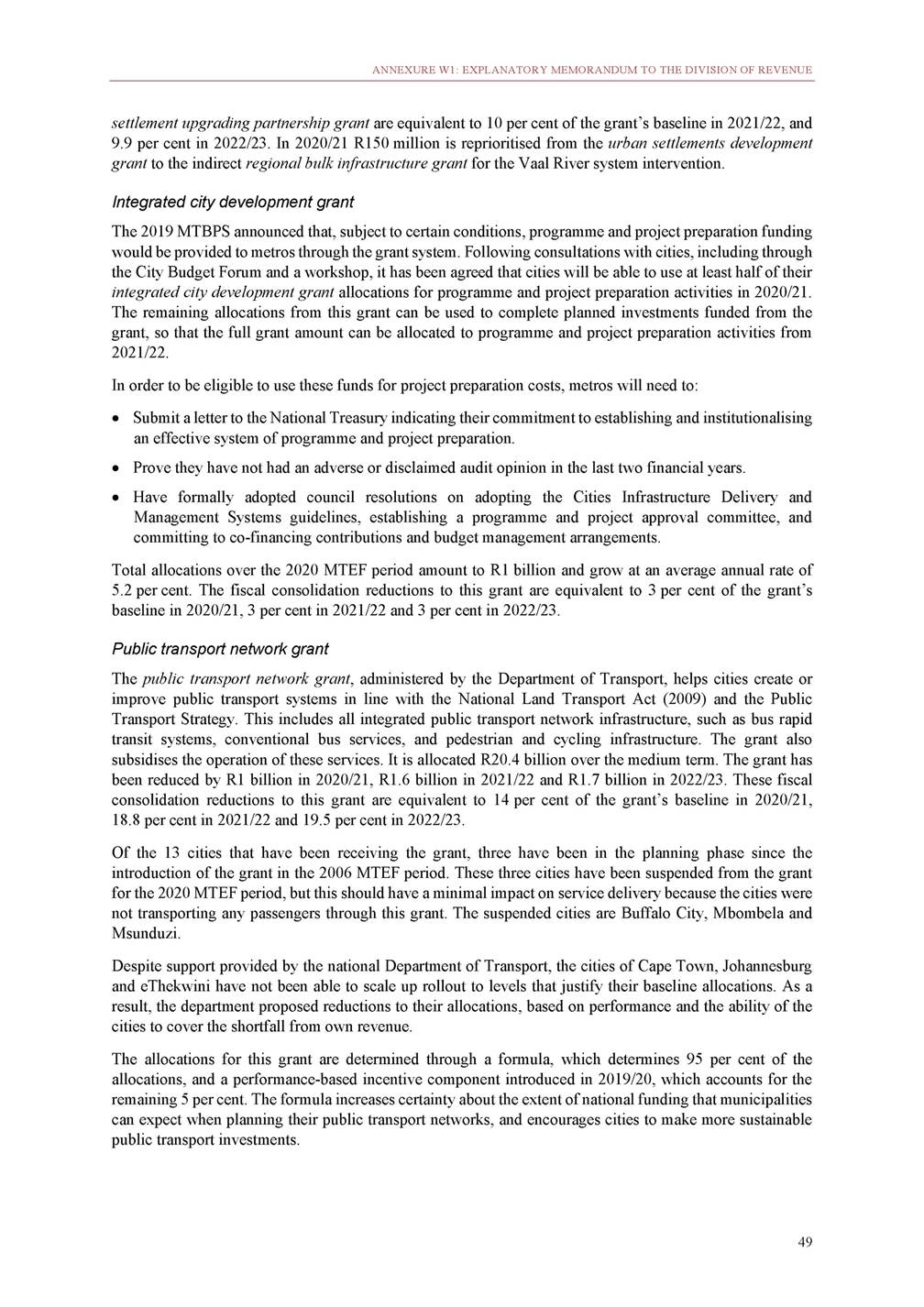

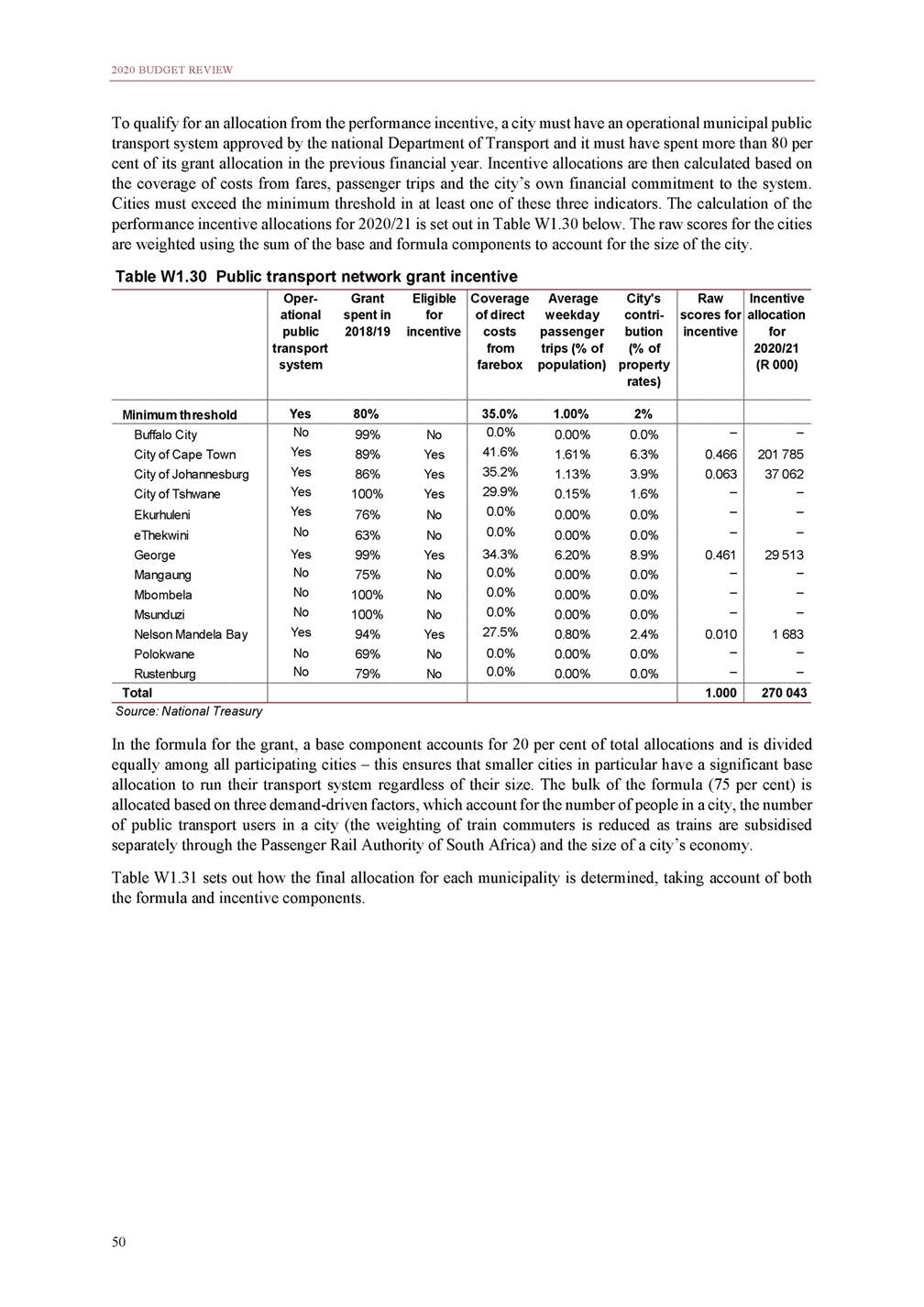

2020 BUDGET REVIEW Rand/dollar exchange rate In 2019, developing-country risk premiums and bond yields continued to fall. In aggregate, developing-country currencies remained largely stable against the US dollar. Countries with high levels of debt and policy uncertainty, such as South Africa, faced considerably more volatility. On average in 2019, the rand’s nominal exchange value fell 5.4 per cent in trade-weighted terms and 1.9 per cent in real terms. Near-term global risks have moderated since the 2019 MTBPS, but the risk of lower growth remains elevated due to trade tensions, in particular between the US and its major trading partners. Debt levels in developing countries have risen sharply since the global financial crisis, and are projected to grow. Debt levels in advanced economies also remain elevated. High levels of government debt will limit fiscal and monetary policy responses to economic shocks. Global trade tensions remain a risk to growth Domestic outlook Real GDP growth slowed from 0.8 per cent in 2018 to a projected 0.3 per cent in 2019. The National Treasury forecasts economic growth of 0.9 per cent in 2020, 1.3 per cent in 2021 and 1.6 per cent in 2022. Table 2.2 Macroeconomic performance and projections Sources: National Treasury, Reserve Bank and Statistics South Africa 16 Rands per dollar Jan 2016 Apr 2016 Jul 2016 Oct 2016 Jan 2017 Apr 2017 Jul 2017 Oct 2017 Jan 2018 Apr 2018 Jul 2018 Oct 2018 Jan 2019 Apr 2019 Jul 2019 Oct 2019 Jan 2020 Indexed (Jan 2016=100) 201620172018 Percentage changeActual 2019 Estimate 202020212022 Forecast Final household consumption0.62.11.8 Final government consumption2.20.21.9 Gross fixed-capital formation-3.51.0-1.4 Gross domestic expenditure-0.91.91.0 Exports0.4-0.72.6 Imports-3.91.03.3 1.1 2.0 -0.4 1.0 -2.1 0.2 1.11.31.6 1.6-0.61.2 0.21.31.9 0.71.31.6 2.32.62.8 1.82.52.8 Real GDP growth0.41.40.8 0.3 0.91.31.6 GDP inflation7.25.33.9 GDP at current prices (R billion)4 359.14 653.64 873.9 CPI inflation6.35.34.7 Current account balance (% of GDP)-2.9-2.5-3.5 4.0 5 086.4 4.1 -3.4 4.54.54.6 5 359.35 676.46 035.1 4.54.64.6 -3.4-3.5-3.7 Figure 2.3 Rising debt in developing countriesFigure 2.4 Emerging-market currencies 18110 EM currency index (RHS) 16 100 14 90 12 Currency weakness against the dollar 1080 Source: Bloomberg and National TreasurySource: Bloomberg